| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 5: Pax Americana, Part I

1933 to 2008

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| First, an Explanation of the Title | |

| The New Deal | |

| New Deal II | |

| Getting Out of the Depression--The Hard Way | |

| The Gathering Storm | |

| Pearl Harbor | |

| World War II | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part II

| The Country Boy From Missouri | |

| Enter the Cold War | |

| China, Korea, and the Pumpkin Papers | |

| "I Like Ike" | |

| Life in the 1950s |

Part III

| The "New Frontier" | |

| Who Really Killed JFK? | |

| The "Great Society" | |

| Nixon Returns | |

| "All the President's Men" |

Part IV

| Years of "Malaise" | |

| The Reagan Renaissance | |

| George Bush the Elder | |

| Clintonism |

Part V

| The Clinton Scandals | |

| Islamism on the Move | |

| The Battle of the Ballots | |

| George Bush the Younger | |

| Angry Democrats, Drifting Republicans | |

| Modern American Demographics | |

First, an Explanation of the Title

The titles of the previous chapters in this work should make sense to anybody who already knows something about American history. For example, Chapter 3 is called "Pioneer America" because it was during that time that large numbers of Americans began to explore and settle the West. However, this chapter's title requires a bit of explaining. In Chapter 4, we saw that the United States qualified as a "superpower" long before 1933, at least as far back as the Spanish-American War. In that sense, the twentieth century was the "American century," just as the sixteenth century has been called the "Spanish century," and the nineteenth century has been called the "British century."

At the beginning of the century, the United States had many competitors, most of them in Europe. World War I knocked out several and exhausted the rest; World War II finished what the first war had started. Only the USA and USSR were left, so for most of the years since 1933, the only serious challenge to US supremacy came from the Soviet Union, and with the end of the Cold War era, the Soviets also fell by the wayside.

The result of the superpower contest is that today, like it or not, the United States is the world's king of business and culture. Much of the rest of the world would like to immigrate to American shores; it wears American fashions, watches American movies, listens to American music, buys American products, and wonders if it can keep its own culture in cities full of American-style skyscrapers and fast-food restaurants. Now with the revolution in communication caused by computers and the Internet, US technology looks absolutely indispensable for maintaining civilization. And unlike its current rivals, the United States is both an economic and a military superpower. Modern Germany and Japan are economic powers but not military ones, and the Soviet Union failed because it had the opposite problem--it tried to support a first-rate army, navy, air force and space program with a Third World economy. Today the United States actually occupies less territory than it did in the past (e.g., Liberia, Cuba, the Philippines and the Marshall Islands were once under American rule, but are now independent nations), but because of its military might, and economic and cultural influence, an outside observer would not be far off the mark in characterizing the United States as an "empire," albeit the most benevolent empire that ever existed. Indeed, for a while I considered calling this chapter "Imperial America" for that reason.

The biggest reason for beginning this chapter in 1933 is because that year saw a paradigm shift in America's political system. So far there have been six presidential elections in US history that have caused critical changes and produced "transformational presidents": those of 1800, 1828, 1860, 1932, 1980, and 2008. 1800 was the first election in which leadership of the federal government switched from one political party to another, 1828 was the first election where the popular vote mattered, and 1860 was the first to elect a Republican president. Because 1860 was soon followed by the Civil War, that was a good place to end Chapter 3, so it seemed appropriate to end Chapter 4 at the next transformational election. 1932 saw the voters reject what they saw as a government that favored big business, in favor of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's "New Deal," and because Roosevelt was one of the most popular presidents in US history, the Democrats enjoyed a numerical majority (among the voters and usually in Congress) for the rest of the twentieth century. To find out what made the 1980 election special, read on.

Finally, the post-1933 era is different from previous times because it has seen incredible growth in the size and scope of the federal government. Before the Great Depression, most Americans believed in Henry David Thoreau's maxim, "That government is best which governs least," but after the Depression struck, many felt that the rugged individualism of the past no longer worked, so Washington introduced various social services to ease the worst of life's hardships, and the modern welfare state was born. Since then the federal government has been praised or criticized for its activist role, depending on which side of the political aisle you're on. We'll come back to that subject in the next chapter, inasmuch as I don't like to begin historical narratives with a commentary. Instead, I will tie the commentary in with some thoughts on where the United States is going from here. Now, where were we when Chapter 4 ended?

The New Deal

For most Americans, the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt couldn't come fast enough. The four-month-period between the election and the inauguration was the grimmest time the nation had seen since the Civil War.(1) Whereas the unemployment rate had been around 3.3 percent for most of the 1920s (full employment by today's standards), by 1933 it had climbed to 24.9 percent--nearly a quarter of all able-bodied Americans were out of work. Industrial production was even worse; the nation's gross domestic product had fallen by nearly half, from $103.7 billion in 1929 to $56.4 billion in 1933.

Despite a number of conferences between Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover, there wasn't a smooth transition, because neither the outgoing president nor the president-elect was willing to compromise. On February 15, 1933, while visiting Miami, Florida, Roosevelt barely escaped an assassination attempt by Giuseppe Zangara, an Italian-born anarchist; the bullets Zangara fired instead mortally wounded the mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak. One day earlier, the governor of Michigan announced a "banking holiday," to keep account holders from pulling their money out of Michigan banks. By the time Roosevelt took office, 22 states had closed their banks, so the first thing Roosevelt did was close all banks around the nation, from March 4 until March 8, until legislation had been passed (the Emergency Banking Act) to restore confidence in financial institutions.

The first hundred days of the Roosevelt administration saw so much activity that it reminded people of the energy Napoleon Bonaparte displayed, during the one hundred days leading up to the battle of Waterloo. Consequently, since then the first hundred days of any presidency has gotten special attention from the public. After the Emergency Banking Act, Roosevelt sent a bill to cut federal salaries and veterans' benefits, and told Congress to get to work on legalizing liquor; the latter act became the Twenty-first Amendment, which repealed prohibition, by the end of the year. During the rest of the hundred days he proposed, and got, the following:

- The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), which eliminated farm surpluses by paying farmers to grow less, or to not grow certain crops at all.(2)

- The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) gave $500 million in direct relief money to the states.

- The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided a quarter million jobs for unmarried young men, by setting up army-style camps in forests, and putting them to work at road-building, planting trees, etc.

- The Public Works Administration (PWA) created more jobs by lending and spending $3.3 billion on building projects.

- The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was launched to protect investors from being swindled in the stock market.(3)

- The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) tamed the Tennessee River, with dams that controlled its floods, harnessed its hydroelectric potential, and made the river navigable as far upstream as Knoxville. In view of its long term effect on Tennessee and surrounding states, this was probably the New Deal's most successful project.

- The Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) slowed down mortgage foreclosures.

- The National Recovery Administration (NRA) set minimum wages and prices, and put "codes of fair competition" on industry.

- The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insured bank deposits up to $5,000.

New Deal II

Roosevelt didn't stop when the hundred days ended. In October 1933 FERA was given a new branch, the Civil Works Administration (CWA), to provide temporary relief for four million unemployed people during the upcoming winter months. The Work Relief Act set aside $5 billion to provide more relief and jobs, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was established to distribute those funds. From the WPA came two specialized agencies: the Federal Arts Project helped professionals like writers and painters, and the National Youth Administration (NYA) provided after-school jobs for college students. A presidential order had already caused the United States to abandon the gold standard, and banned ownership of gold in the form of money; in January 1934 the dollar's gold value was stabilized at 59.06 cents.

By the beginning of 1935 Roosevelt was talking about a second New Deal. This program would have reform, rather than recovery, as its theme, and it would cause more drastic changes than the first New Deal. To the agencies mentioned in the previous paragraph, he added the Social Security Act, which guaranteed a pension for retirees(4). The Wagner-Connery Labor Relations Act gave workers the right to organize and bargain collectively, and the Strikebreaker Act helped strikers by making it illegal to transport strikebreakers from one state to another. These were followed in short order by the Resettlement Administration (RA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and the Public Utility Act. Finally, he had Congress raise taxes on individuals and businesses with the largest incomes. By the end of the 1930s, the highest income tax rate had been raised to 79%, the corporate income tax rate was doubled from 12 to 24%, and Roosevelt tacked on an excess profits tax, an excise tax on dividends, liquor taxes, a capital stock tax, and a 2% Social Security payroll tax.

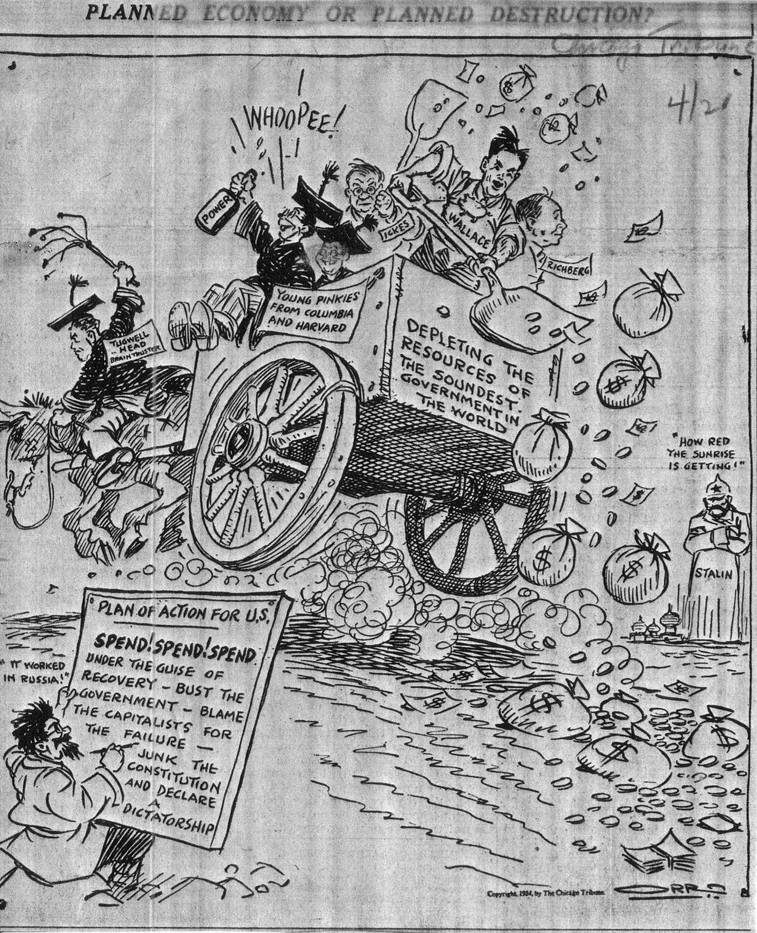

Though FDR was the closest thing to an aristocrat that American society could produce, he didn't get along well with other rich Americans. They called him a traitor to his social class, and names like "That Man in the White House," or "Franklin Double-Cross Roosevelt." From their point of view, it was irresponsible to spend money you did not have, as FDR was doing with the federal government, and they warned (rightly, as it turned out) that his activism would be the end of the nation as they knew it. In addition, FDR spooked business owners, corporations and would-be investors with his higher taxes and "regime uncertainty." The latter term meant that they could not tell what the government would do next, so they felt it was safer to avoid investing; that helped to ensure that the Depression would last for the rest of the 1930s. By contrast, the working class loved Roosevelt. They felt he really cared for them, not only because of the new government programs, but also because he reassured them by telling them what he was doing, on regular radio broadcasts called "fireside chats." Consequently it is hard to have a neutral opinion of him; most people who know anything about FDR will rank him among either the best or the worst presidents in US history.

During his first term, Roosevelt's most dangerous opponent was not a Republican but Louisiana Senator Huey Long, the most colorful politician to come from a state that has long been known for colorful characters. Both brilliant and a persuasive, fiery orator, Long first gained national attention when he was elected governor of Louisiana in 1928. He has been called the only American politician to become a dictator on the state level, but unlike real dictators, he did not imprison or kill his enemies. Instead, as governor he quickly made himself popular by handing out free textbooks and building lots of roads, bridges, schools and hospitals, while at the same time he had total control over the state and municipal governments, using a combination of corruption and chutzpah (he once boasted, "I can buy legislators like sacks of potatoes."). He was impeached in 1929 on charges that ranged from blasphemy to bribery and misappropriation of state funds, but the case was dropped. Then in 1930 he won a seat in the US Senate, but he did not go to Washington until January 1932, after making sure that a yes-man, Alvin Olin King, would succeed him as governor; this allowed him to keep control over the state political machine from a distance.

Huey Long came to be known by his admirers as the "Kingfish," after a character on the popular radio program "Amos n' Andy." In 1934 he put forth a populist program to eliminate poverty, which he called the "Share Our Wealth Society." This wealth redistribution plan proposed limiting individual incomes to $1 million a year, transferring amounts in excess of that to guarantee every family a minimum income of $5,000 a year; he also offered a pension of $30 per month to elderly people who had less than $10,000 in cash. To explain this program and his plans for the future, he wrote two books, Every Man a King and My First Days in the White House.

Long supported Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election, playing an important role in keeping Roosevelt's delegates loyal at the convention until he was nominated, but Roosevelt did not return the favor, so Long turned against him after that.(5) In the Senate he filibustered several New Deal measures, denounced the Federal Reserve system, which he thought was the cause of the Great Depression, and because of his books, some discussed him as a future presidential candidate. This was what really made him dangerous to Roosevelt, but he wasn't going to compete with FDR for the Democratic nomination; according to Thomas Harry Williams, the author of a Pulitzer prizewinning biography of Long, the plan was form a "Share the Wealth" Party and run on that. However, before Long could spread his form of dictatorship beyond Louisiana, he was assassinated by the son-in-law of a political opponent (September 10, 1935). For decades afterwards his family remained active in politics: his widow finished out his term in the Senate; his brother Earl served as governor of Louisiana on three occasions; another brother, George, went to the House of Representatives; his son Russell was a senator from 1948 to 1986.

Getting Out of the Depression--The Hard Way

1936 was the best year of FDR's presidency. Because the voters tend to like a president who makes major changes in national policy, Roosevelt had no trouble getting the Democratic nomination again. He could not have known that future Americans would refer to those who grew up in the 1930s and 40s as "the Greatest Generation," but he predicted as much in his acceptance speech: "To some generations much is given. Of other generations much is expected. This generation of Americans has a rendevous with destiny." However, he also predicted class warfare in his second term, when he said, "The royalists of the economic order have conceded that political freedom was the business of the Government, but they have maintained that economic slavery was nobody's business . . . These economic royalists complain that we seek to overthrow the institutions of America. What they really complain of is that we seek to take away their power." Conservatives in both major parties winced at this promise to "soak the rich."

For their candidate, the Republicans settled on Alfred M. Landon, a former Progressive, a wealthy businessman and the current governor of Kansas. Landon seemed to know it was a losing battle, because he only campaigned half-heartedly; he was mainly known for saying, "I believe a man can be a liberal without being a spendthrift!" and for campaign buttons that showed his face in the center of a sunflower.

The Kansas Sunflower.

Results for the 1936 presidential election were the most lopsided since the introduction of the popular vote, more than a century earlier. Roosevelt got 60.8 percent of the vote and carried every state except Maine and Vermont; Landon didn't even win in his home state.(6) The anti-FDR vote was split as well, between Republicans and the short-lived Union Party, which nominated North Dakota Congressman William Lemke and promoted a right-wing extremist platform; it got 2 percent of the vote. Thus, the Kansas Sunflower wilted, and FDR was in bloom again.

The 1936 election was the first to place much emphasis on polling for public opinion. A popular magazine, Literary Digest, mailed out ten million questionnaires, and based on the more than two million that were returned, predicted that Landon would win by a landslide. Apparently most of the readers were Republicans; the poll's failure to choose the winner was so embarrassing that Literary Digest went out of business a few months after the election. Meanwhile, an organization called the American Institute of Public Opinion, founded just a year earlier by George Gallup, did better, by randomly sampling 5,000 people. Gallup won twice on Election Day, because he not only predicted that Roosevelt would win, but also that the Literary Digest poll would be wrong. His success encouraged him to conduct more polls, and the Gallup Poll has been a regular feature of American politics ever since.

Whereas Congress and most of the American people had given Roosevelt a blank check during his first term, the second term saw him run into significant opposition. It started in the one branch of government he hadn't been able to control--the Supreme Court. In the thirty-five years before FDR, only one other Democrat (Wilson) had been president, so most of the Supreme Court justices were conservative, Republican-era appointees. In fact, the chief justice at this time, Charles Evans Hughes, was a former Republican candidate for the White House. During the first term the court had handed down a series of measures cutting back the strength of the New Deal; the most serious decision killed the NRA by declaring it unconstitutional, because it was part of the executive branch of government but had legislative powers. Then it struck down the AAA, arguing that its rules and tax policies infringed on the rights of the states.

Roosevelt's answer to this was called "court-packing." To him, the Supreme Court justices were "nine old men" who had been on the bench too long to understand "the facts of an ever-changing world." In early 1937 he proposed that whenever a justice reached the age of seventy, a new justice would be added to the court whether his predecessor stepped down or not, and this would go on until the old justices got out of the way or until the total number of justices reached fifteen, whichever came first. To Roosevelt's surprise, the proposal was very unpopular, even in his own party. Jim Farley (see the previous footnote) tried to twist the arms of senators by declaring that those who had gotten elected by riding "on the president's coattails" should vote for the bill, but all this did was make sure that angry senators would vote against the bill.

As it turned out, Roosevelt wouldn't have felt the need to pack the Supreme Court if he had been a little more patient. The court was friendlier to the New Deal after the showdown, allowing reforms like the Wagner Act and the Social Security Act to go into action. It didn't even interfere when Congress passed a second Agricultural Adjustment Act in 1938. And during the next six years, all nine justices died or retired, allowing Roosevelt to replace them with New Dealers. There was an embarrassing incident with the first new justice he appointed, Alabama Senator Hugo Black, when it was discovered that Black was a former member of the Ku Klux Klan, but the Senate confirmed the appointment, and by the end of his second term, Roosevelt had the compliant court he wanted.

During the first term, there was some economic recovery, either because of the New Deal (the Democratic view) or in spite of it (the Republican view). By 1936 the unemployment rate had fallen to 14.3%--a lot better than the 1933 figure of 24.9%, but it meant there was still a long way to go. Roosevelt could also announce that for the first time in fifty-five years, a whole year had gone by without a national bank failure. Then in 1937 came a recession within the Depression, and joblessness shot back up to 22%. Sometimes called the "Roosevelt Recession," this slump had four causes: (1) FDR didn't understand economics, (2) he cut back on New Deal spending too quickly, in order to balance the budget, (3) he preferred political compromise over controversial commitments, and (4) Social Security taxes began to be taken out of paychecks, leaving workers with less take-home pay. Consequently it took until 1941 for unemployment levels to return to 1936 levels.(7)

Besides poverty, idleness, and misery all around, the Great Depression also generated labor unrest. Much of this was sparked by the Wagner Act and the Strikebreaker Act, which encouraged the formation of new unions because they gave more power to the workers. The result was more strikes than usual, and sometimes massive violence, to the dismay of everybody. The worst cases of labor violence were as follows:

- "Bloody Harlan County": From 1931 to 1939, this county in southeastern Kentucky was almost a war zone between "union men" and "company men," as the United Mine Workers attempted to unionize the coal mines in one of the poorest areas of the country. The struggles were eventually commemorated in songs written by Florence Reece, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Natalie Merchant. And that wasn't all; history repeated itself with another Harlan County miners' strike in 1973, which lasted for thirteen months.

- July 1934: 68 are shot, and more are beaten in Minneapolis during a truck drivers' strike. Martial law is declared, and the National Guard takes over the market district.

- August 1934: 150,000 workers in the textile industry go on strike, resulting in violence and rioting in the textile centers of north Georgia and the Carolinas.

- January 1937: Michigan experiences a spectacular 44-day sit-down strike against the auto industry. Unlike previous strikes, this time the workers not only refused to work, they wouldn't even leave their workplaces. General Motors agreed to negotiate, and sit-down strikes spread to the rubber, steel and textile industries, before they were outlawed.

- Spring 1937: 75,000 steelworkers go on strike in Pennsylvania and Ohio. The introduction of strikebreakers turned this strike violent.

- May 1937: The "Memorial Day Massacre." During another steelworkers' strike in Chicago, police fire on the demonstrators, killing ten and wounding at least fifty. Roosevelt rebuked both the CIO (see below) and Republic Steel, the company they were striking against, declaring, "A plague on both your houses."

The one who welcomed those workers was the president of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis. The UMW had been declining for many years, but in the new environment, membership quickly tripled, from 150,000 to 450,000. Lewis thought unions should be organized along industrial lines, taking in everyone who works in a certain factory or industry, regardless of what they did. The other AFL unions hesitated, and at the AFL's 1935 convention, Lewis declared that the organization had "a record of twenty-five years of constant, unbroken failure." William L. Hutcheson, the president of the Carpenter's Union, called Lewis a "big bastard," and Lewis punched him out in public. Two weeks later Lewis teamed up with the presidents of seven other unions, and they left the AFL to form the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO). Under Lewis' leadership, the CIO grew rapidly, but so did its rival, the AFL. By 1941, all labor unions had a total of 11 million members between them.

In 1955, the AFL and CIO put aside their differences and reunited, forming today's AFL-CIO.

Altogether the New Deal was a revolution in the way government worked, but it was also an incomplete revolution, and Roosevelt meant it to be that way. He insisted that the New Deal's purpose was to save capitalism, not to destroy or replace it, so he did not try to nationalize banks, railroads or industries while they were down for the count. The difference was that whereas in the past most political power simply went to big business, now big business had to compete with big labor and big government.

We also should remember that the recovery from the Depression was unusually long. Never before, and never since, did it take more than a decade to climb out of a recession or depression.(8) Besides the previously mentioned reasons of high taxes and "regime uncertainty," neither of which is a good idea when the economy is in bad shape, FDR's programs probably did more to slow down the recovery than they did to stimulate it. When he put people back to work by giving them "make work" jobs, those jobs added to a growing national debt that the taxpayers would eventually have to pay, and they did not restore or develop the country as much as jobs created by private industry. It also didn't help that political motivation may have been behind some of the job-creating. For example, scholars like Gavin Wright, John Joseph Wallis, Jim F. Couch, and William F. Shughart II noted that a lot of WPA projects went to Western states that FDR barely won in 1932, guaranteeing he would carry those states in 1936, while the much poorer South received the least amount of WPA assistance, because it was likely to vote Democratic no matter what FDR did.

I have pointed out elsewhere (e.g., Chapter 13 of my European history) that the various aspects of economic development, such as the building of factories and railroads, are most successful when the government does not get involved. Henry Hazlitt explained the difference between private and government-made jobs this way, in his 1946 book, Economics in One Lesson:

"For every public job created by [a] bridge project a private job has been destroyed somewhere else. We can see the men employed on the bridge. We can watch them at work. . . But there are other things that we do not see, because, alas, they have never been permitted to come into existence."

The Gathering Storm

The isolationism that characterized most Americans in the 1920s continued into the 1930s; the United States was too preoccupied with its own problems to care much about what happened abroad. Meanwhile, strong leaders seized power in many other nations: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey, Benito Mussolini in Italy, Joseph Stalin in Russia(9), Chiang Kai-shek in China, and Adolf Hitler in Germany, to name a few. As in the United States, the people accepted these leaders, because they were desperate for anyone who could get them out of the problems their countries faced. The difference was that Roosevelt was a reformer, but most of the others were outright dictators. Many of them had alarming solutions to their countries' problems, especially Hitler, who pulled Germany out of the Depression by preparing for war. Because no one was willing to stop them, the dictators made these gains in the 1930s:

- 1931: Japan invades Manchuria, installing the last emperor of China as a puppet ruler there.

- 1935: Mussolini invades and conquers Ethiopia, avenging a defeat Italy had suffered there, nearly forty years earlier.

- 1936: Hitler sends troops into the demilitarized Rhineland, a clear sign that he was no longer going to abide by the terms of the Versailles treaty. In the same year he and Mussolini formed an alliance, which they called the "Rome-Berlin Axis."

- 1936: Mussolini and Hitler support Francisco Franco's bid to become dictator of Spain. When Stalin backed the loyalist government, a three-year civil war followed, which was more like a war game for the non-Spaniards who participated.

- 1937: Japan invades the rest of China.

- 1938: Hitler annexes Austria, and through the Munich agreement, carves up Czechoslovakia.

- 1939: Mussolini invades Albania, giving him a bridgehead for future Balkan conquests.

- 1939: Hitler moves to take the rest of Czechoslovakia, and when he invades Poland, World War II begins.

- 1940: Japan joins Germany and Italy, making it a "Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis."

From this time on, Roosevelt pursued an "interventionist" policy, which was the opposite of isolationism; the United States would get involved in foreign affairs to protect its interests. Because he felt that the right side to support was the one that wanted to maintain order and the balance of power throughout the world, he would do whatever he could to help those opposing conquest, without committing Americans to fight. However, for the moment he could only use diplomacy, because the US armed forces had been allowed to run down since World War I ended. The army of the 1930s was out of date, and too small to defend a nation the size of the United States. Horses were still used to pull artillery pieces, American tanks were no match for Hitler's new panzer divisions, new recruits had to drill with broomsticks when there weren't enough rifles to go around, and even taxis were used to transport troops on maneuvers, as if they were training to fight the battle of the Marne all over again. A few officers like Billy Mitchell, Adna R. Chaffee and George S. Patton Jr. called for more modern tanks and airplanes, and in 1938 Congress authorized funding to enlarge the army, modernize its equipment, and build a two-ocean navy. The sleeping American giant began to wake up at last.

As the 1940 presidential election approached, the Republicans found themselves without a credible platform, and without a credible candidate. The three leading candidates, Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, and Thomas Dewey, a popular district attorney from New York, all had flaws: Vandenberg and Taft were staunch isolationists, unlikely to win the votes of those who felt otherwise, while thirty-eight-year-old Dewey was too young. The Republican compromise was a surprising one--they nominated Wendell Willkie, a corporate lawyer from Wall Street, though he had never held a political office in his life, and had previously been an active Democrat, only switching parties in 1939.

For the Democrats, the big question was: will FDR run again? The voters would be reluctant to change presidents while war raged overseas, but keeping Roosevelt would break one of the oldest taboos in American politics: no president should serve a third term. Back in Chapter 3, we saw that tradition started when George Washington insisted on retiring, instead of running for a third term. Thomas Jefferson put more meaning into it when he stepped down at the end of his second term, though Napoleon and the Barbary Pirates hadn't been defeated yet. Most of the presidents after Jefferson kept the tradition; those that didn't were struck down either by their parties or by the voters. This time, the conquest of France by Nazi Germany, and other bad news from overseas, persuaded FDR that he was the only man for the job, so he said "yes." His vice-president, John Nance Garner, ran against him, because "Cactus Jack" was a conservative, and by this time he had become an opponent of Roosevelt's liberal economic and social policies. Roosevelt had no trouble defeating Garner for the nomination, and replaced him with a more loyal vice president, his Secretary of Agriculture, Henry Wallace (see footnote #2).

Wendell Willkie's stand on the issues was wishy-washy; he attacked the New Deal and FDR's support for the Allies, but promised to keep parts of both policies if elected. The best thing he had going for him was the third-term issue, and his response to Roosevelt's decision was, "Just think, here is a candidate that assumes that out of 131 million people he is the sole and only indispensable man." A Republican campaign slogan emphasized the no-third-term tradition: "Washington wouldn't. Grant couldn't. Roosevelt shouldn't." However, it wasn't enough to overcome nervousness about Axis advances in the war, and this convinced a majority of Americans to break tradition--at least this time.(10) In November Willkie won ten states, a better performance than the Republicans had done in 1932 and 1936, but Roosevelt still carried the rest of the country.

Americans weren't divided on which side to support when World War II broke out; the behavior of the Germans, Italians and Japanese put their sympathies firmly on the side of the victims. Instead, the question was whether the United States should enter the war. Many Americans felt the war was none of their business, and they formed an antiwar group, the America First Committee, in September 1940. They argued that when interventionists talked about defending England, they really meant defeating Germany; that Roosevelt's policy of aiding the Allies would eventually draw the United States into the war (correct); and that Hitler and the other dictators would never be a threat to the United States, if left alone (incorrect). During its short existence (the organization was discredited by Pearl Harbor), it had Charles Lindbergh, the aviation hero, as its chief spokesman, and quite a few members who were either important then, or would be later on: Herbert Hoover, General Robert Wood (the head of Sears Roebuck), future presidents John F. Kennedy and Gerald Ford, R. Sargent Shriver (the future head of the Peace Corps and a vice presidential candidate), Potter Stewart (a future supreme court justice), poet e. e. cummings, authors Gore Vidal, Sinclair Lewis and Sherwood Anderson, movie director Walt Disney and actress Lillian Gish.(11)

Despite the efforts of the America Firsters, the interventionists were one step ahead of them. To start with, they set up their own organization first, the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies. In addition to the previous expansion of the armed forces, Congress voted to build 50,000 airplanes, and to conscript 16 million men in a peacetime draft. To reduce opposition from Republicans, Roosevelt put Republicans in charge of the war and navy departments in the Cabinet. During the battle of Britain the new British prime minister, Winston Churchill, appealed to the United States for assistance: "Give us the tools and we'll finish the job." Accordingly, Roosevelt worked out a deal where the United States gave the British fifty destroyers left over from World War I, in exchange for ninety-nine-year leases on seven British bases in the western hemisphere. For the war in the Pacific, he cut off shipments of scrap iron to Japan (the Japanese had been turning it into guns), and started loaning money to China.

Roosevelt, like Wilson in 1916, promised not to send American soldiers off to war, but his neutral-in-name-only policy made sure it would happen anyway. After the 1940 election he called for a major gear-up of war-related industries, declaring that "We must be the great arsenal of democracy." In early 1941 Congress approved Lend-Lease, a loan program that would send the Allies, especially the British, whatever war materials they needed on credit. This was extended to the Soviet Union after it entered the war, in June 1941.

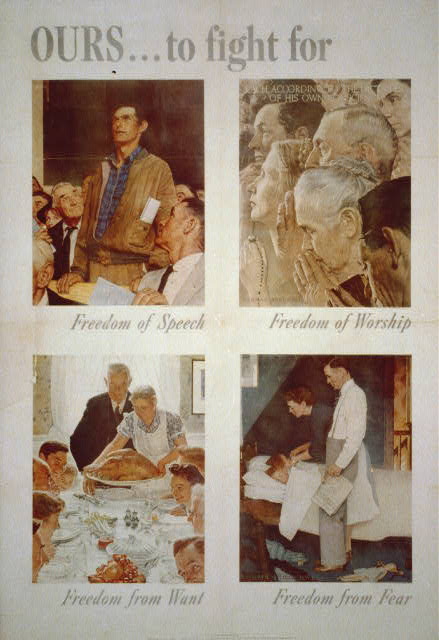

One day in August 1941, FDR went on what he called "a fishing trip," sailing out of New London, CT on his yacht, the Potomac. He did fish for a day off Martha's Vineyard, but then was secretly transferred to a cruiser, the Augusta, and taken to Newfoundland. There at Placentia Bay, Winston Churchill arrived on a British battleship, the HMS Prince of Wales, and Roosevelt met with him to write the Atlantic Charter. Previously the president had listed for Congress "four essential human freedoms" which he felt were worth fighting for: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

Now Roosevelt could put all his ideas concerning the war down in writing, and this would be the first of several meetings to create a future organization to replace the League of Nations, namely the United Nations. But these lofty, diplomatic goals would have to wait until after the war, so here the United States and Britain also began to coordinate their military activities.(12) Soon after the meeting, Congress authorized the arming of merchant ships, and American naval vessels were ordered to sink German submarines on sight. It would be a few more months before the United States was formally at war, but the US Navy and Merchant Marine were already fighting on the side of the Allies. Roosevelt justified this with an oft-quoted statement about the need to fight for freedom: "Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety."

Pearl Harbor

Ironically, Adolf Hitler did more to end the Great Depression than Roosevelt and the New Deal did. With millions of men either drafted into the armed forces, or working in factories to produce war materiel, the unemployment rate plummeted, and American workers could gratefully put the Depression behind them at last.

While most of the nation's wartime attention was concentrated on the European theater, the blow that brought the United States into World War II came from the Pacific. The war in China had not generated as much news as Hitler's blitzkrieg because it was a long uphill struggle for the Japanese. Moreover, the Americans had assumed the same attitude held nearly fifty years earlier by China and Russia--that if it came to war, Japan was an upstart nation which could easily be put back where it belongs.

Conquered areas of China could supply almost unlimited manpower, but what the Japanese war machine really needed were resources which could not be found there, especially oil and metals. The nearest places to get those resources were Siberia and Southeast Asia, and two probing attacks by the Japanese against the Soviets (one near Vladivostok, one in Mongolia) were defeated, so the Japanese decided Siberia wasn't worth it. With Southeast Asia, the Japanese expected their main obstacle to be the United States, because the other colonial powers in the region were tied down by the fighting in Europe. They tried using diplomacy to end the current US embargo on Japan, but the Americans would not budge from their chief demand, that Japan must withdraw from China.

With all the land in the Pacific made up of islands, naval units would be more important than they were in Europe. This meant that the key to victory was to take out as many enemy ships as possible in the first strike. And because the largest American base in the Pacific was in Hawaii, at Pearl Harbor, Japanese pilots spent much of the 1930s training for a possible air strike on Pearl Harbor. November 1941 saw Japanese diplomats come to Washington, for more negotiations with Roosevelt's Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, while a task force of six Japanese carriers secretly headed from the Kurile Islands to Hawaii.

The Japanese attack, on December 7, 1941, caught the United States totally by surprise. By this time there was some expectation that the Japanese would try hitting targets important to US interests, but few thought Pearl Harbor would be one of those targets. Moreover, most Americans had their thoughts on other subjects, like getting ready for the upcoming Christmas. Suddenly, Japanese planes and submarines struck the island of Oahu at 7:45 A.M. It was a Sunday morning, and the American ships in the harbor had minimal crews on board, because most navy personnel preferred to spend their weekends ashore. Antiaircraft ammunition was kept locked in boxes, with officers on watch holding the keys. The attacking planes were detected on radar, but those who saw them incorrectly identified the aircraft as American B-17s from the US mainland. Thus, the situation was hopeless for those who tried to fight back. By 10 o'clock, all eight battleships in the harbor and thirteen other vessels were sunk or heavily damaged, and almost 200 American aircraft had been destroyed, most of them on the ground. The death toll was 2,345 military and 57 civilians killed, and about half as many wounded. The Japanese in turn lost twenty-nine aircraft, five mini-submarines and sixty-five men.

The best news for the Americans was that no aircraft carriers were at Pearl Harbor on that day; before long they would prove to be the most important ships of all. And while the Japanese may have won that battle, they also set into motion a series of events that would result in them losing the war. For a start, the battle silenced the isolationists, uniting Americans in a desire for vengeance. The next day Roosevelt addressed Congress, calling December 7, 1941 "a date which will live in infamy," and asked for a declaration of war against Japan. The vote was near-unanimous, with only one member of Congress voting against the declaration.

Nor was that all. In Europe, Churchill had previously promised that if war broke out between the United States and Japan, Britain would join the Americans; now he pushed for a declaration so fast that Britain actually declared war on Japan before the United States did. In the Axis camp, Hitler and Mussolini were excited by the Japanese strike, and on December 11 both of them declared war on the United States. It was one of the rashest decisions ever made. At this stage of the war, the Italians were faring so badly that Mussolini was forced to do whatever Hitler was doing, but as a World War I veteran, Hitler should have remembered that the United States was the main reason why Germany had lost the last war. The battle of Britain showed he couldn't even transport the Wehrmacht across the English Channel, so taking the war to America was right out; he could only fight the Americans if the Americans came to him. Perhaps he was tired of Roosevelt's wholehearted support for his enemies, and felt the United States needed to be taught a lesson. Whatever his reasons, two previously separate conflicts, one in Europe and one in the Pacific, now merged to become a true worldwide war.

World War II

As this narrative did with World War I, you will not see a blow-by-blow description of World War II here. This section will concentrate on what was happening back home in the United States, because the conflict itself has already been covered in these history papers:

- The European Theater

- The Russian front

- Battles in the Middle East

- Battles in Africa

- Japan vs. China

- The Japanese homeland

- The war in Southeast Asia

To win World War II, the civilian population of the US was mobilized to a decree that could only be matched by the efforts made by Americans to win World War I. Indeed, the US government would exert far more control over the economy than the Axis dictators had over theirs. The War Production Board (WPB) organized industry for war, much like the War Industry Board had done in World War I. The War Food Administration did the same thing for agriculture, increasing the output of farms even though they had a manpower shortage. Taxes were raised, and bonds were sold, both at unprecedented levels. Vital materials like gasoline, rubber and copper were rationed for the time being, and Americans grew "victory gardens" to make sure there would be enough fruits and vegetables for the troops. There was some labor unrest at first, until the AFL, CIO and the leaders of the railroads agreed to a no-strike pledge. Hollywood played its part by producing movies that supported the Allied cause, expressing far more patriotism than its actors and directors have been able to show in the decades since.(13)

After Pearl Harbor millions of men and women volunteered to do whatever they could to help win the war. So many young men enlisted in the armed forces that the draft was no longer needed, while women joined the Red Cross and took jobs left by men going off to war. The result was a relaxation in the standards that previously restricted many jobs to white men; women like the famous "Rosie the Riveter" now worked in factories, shipyards, etc. Consequently the number of working women increased, from 12.7 million in 1940 to 20 million in 1944. After the war, however, a lot of them were discharged so that returning servicemen could have their jobs back. Black Americans also saw improved job opportunities, and during the war, many of them moved from the South to Northern cities to take advantage of them.

At the time, there was real concern that German ships and submarines would attack from the Atlantic, or that Japan would repeat Pearl Harbor with a strike on the US mainland. Fortunately it didn't happen, but it led to one of the more shameful events in twentieth-century America--the internment of Japanese-Americans. In 1941 there were 126,000 people of Japanese descent living in the 48 states, three fourths of them in California. The War Department saw them as a potential risk, so Roosevelt and Earl Warren, the Attorney General of California, ordered the removal of 112,000 Japanese-Americans in the states of California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona, to get them away from the Pacific coast. They went to ten relocation centers that were really prison camps, guarded with barbed wire and armed guards, though none of them had been charged with any crime.(14)

Some of the discrimination was racially motivated; most Americans of German or Italian ancestry were not arrested or otherwise bothered. Nor did it matter that only a third of the detainees were immigrants; most had been born in the United States to Japanese parents. They were not allowed to return home until after the war, and many lost both their homes and their jobs by then, because in the camps, they could not carry proof of what they had owned previously. Not until 1976 did Washington admit that the relocation was wrong, when then-President Gerald Ford said so. Two laws passed by Congress later on, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and the Civil Liberties Act Amendments of 1992, awarded reparation payments of $20,000 to each surviving detainee.

For Europe, the United States could send ships and warplanes almost immediately, but the ground forces faced the same logistics problem that they had in World War I; it took nearly a year to train the troops and ship enough of them across the ocean to make a difference. In the four years after 1938, the US Army grew in size from 185,000 men to three million, but the new soldiers were an inexperienced force; it would take quite a bit of combat before they were as good, man for man, as their battle-hardened opponents. Moreover, because the United States had been at peace for more than twenty years, its officers were more likely to have administrative skills than fighting skills. Fortunately there were fighting generals handy, and one of the newest was a former barefoot boy from Abilene, Kansas, named Dwight David Eisenhower.

Eisenhower had been in the army since 1911. For two years after finishing high school, he tried to save up enough money to go to college; then he got an appointment to West Point because it promised free college tuition. However, he turned out to be a natural leader when he graduated from West Point, and enjoyed training or teaching others, so he decided to make a career out of the military. During World War I he was put in charge of one of the first American tank corps, but to his disappointment, the war ended before his unit could be sent to Europe. After that he served on the staff of General Pershing in the 1920s, and on the staff of General Douglas MacArthur in the 1930s, which included four years in the Philippines. Although MacArthur called him the best officer in the army, Eisenhower was only a lieutenant colonel at the beginning of World War II, because the army's highest ranks were reserved for officers who had been in longer than he had.

With the expansion of the army just before World War II, Eisenhower's abilities were suddenly in demand. He was a staff officer in Louisiana, having recently been promoted to brigadier general, when he heard the news from Pearl Harbor. One week later the army chief of staff, General George C. Marshall, called Eisenhower to Washington, D.C., and put him in charge of the War Plans Division. There he made the argument that Hitler was the main enemy and the European theater of the war should take precedence over what happened in the Pacific. General Marshall and President Roosevelt agreed, and in March Marshall promoted Eisenhower to major general. Then in June Eisenhower was put in command of all American forces in Europe. By the end of 1944 he was a five-star general, the highest rank in the history of the US armed forces.

Eisenhower wanted to begin the liberation of western Europe as soon as possible, and Stalin demanded it, because this would force the Germans to ease the pressure they were exerting on the Russian front. Churchill, however, convinced Eisenhower that American soldiers weren't ready yet, and Britain was in no shape to lead an all-out Allied offensive, so the first European campaign involving US ground forces hit an area peripheral to Hitler's Fortress Europe--North Africa. In November 1942, while Germany and the Soviet Union were locked in the battle of Stalingrad, an Allied force that was 2/3 American, with some British and Free French troops, landed in Morocco and Algeria ("Operation Torch"). They quickly pushed east to Tunisia, where they met the British Eighth Army coming out of Egypt, and thus completely swept the Axis out of North Africa. 1943 saw this followed up with an invasion across the Mediterranean, first with landings on Sicily, then on the Italian mainland. The Italians surrendered at this point, but Hitler rushed some German divisions into the peninsula to save the situation, and those troops dug in and fought back bitterly; it took nine months for the Allies to advance from Salerno to Rome. Meanwhile in the air, American and British commanders worked out a strategy for bombing Germany at all hours of the day and night.

On June 6, 1944, two days after the liberation of Rome, the long expected Allied offensive from the west began, with the D-Day landings in Normandy, France.(15) They succeeded in liberating Paris in August and Belgium in September, and penetrated Germany's first line of defense, the Siegfried Line.(16) However, the first assault on the Netherlands, a series of airborne landings called Operation Market Garden, failed to achieve a breakthrough on the northern end of the front; most of the Dutch would remain under Hitler's tyranny until the spring of 1945. An even more shocking reverse came with the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, when the Germans launched a counterattack that briefly recaptured eastern Belgium, except for the city of Bastogne. For the Americans, this was the bloodiest battle of the entire war: 19,000 GIs killed, 47,500 wounded, and 23,000 captured or missing. Americans were particularly appalled by news of the Malmedy massacre, in which 150 American soldiers were shot after they surrendered. Fortunately for them, German losses were even heavier, and the Allies were able to contain this advance before it reached the English Channel or broke into France. After that came the final Allied offensive; in March and April of 1945 the Americans, British, Canadians and French surged across the Rhine into the heart of Germany. Along the Elbe River, as well as in Austria and in western Czechoslovakia, they met a solid Soviet line advancing from the east, and together they crushed the Third Reich out of existence.

Here is a bit of trivia about Patton you may not have known; he was an athlete at the 1912 Olympic Games, held in Stockholm, Sweden. The 27-year-old Patton entered the Pentathlon, a combination of fencing, shooting, horseback riding, swimming and running--five appropriate macho sports for a future general. Patton did well enough overall to come in fifth place, but the final score was controversial. The reason why he did not win a medal was because the judges ruled that for the shooting, Patton completely missed the target on his final handgun shot. Patton, however, argued that he did not leave a mark on the target because his bullet went into the same hole left by the previous shot. Do you remember the story about how Robin Hood entered an archery contest, another archer hit the bullseye in the target, and then Robin Hood hit the exact same spot, splitting the first arrow? Patton may have done the same thing with a pistol, one of the most amazing acts of marksmanship in history. If he had gotten credit for that, he would have been remembered as a sports hero, as well as a war hero.

In the Pacific, a Japanese carrier force heading for Australia was sunk, in the battle of the Coral Sea (May 1942). Then in June another Japanese carrier force approached Hawaii, this time with the objective of capturing Midway Island, to use as an advance base for invading the rest of Hawaii. Part of this force broke off to capture Attu and Kiska, two of the Aleutian islands between Alaska and Siberia; this was the closest any Axis invaders got to the North American mainland. The rest of the fleet went down in the battle of Midway. With that, Japanese domination of the sea ended, and the tide of the war turned against Japan.

The Japanese invasion of the Aleutians was not followed up with other moves in the northern Pacific; it was merely intended to distract Americans during the battle of Midway. Most Americans did not even pay attention to the Japanese garrisons stationed there, and tundra conditions were so harsh that US forces waited for nearly a year to take the islands back. That operation began with the US 7th Division landing on the island of Attu on May 11, 1943. They found the going extremely tough because of mud and extreme cold weather. In fact, more casualties were caused by frostbite and disease than from the fierce Japanese resistance. Over the course of eighteen days, the Japanese were herded into a small pocket on the island, whereupon they staged a furious but futile suicide charge, from which almost none survived. This was the first "Banzai charge" that would later be reported in other Pacific battles during the war.

Then on August 7, 1943, a force of more than 34,000, including 5,300 Canadians, landed on the other occupied Aleutian island, Kiska. This time the result was quite different; for five days the troops looked for the enemy, sometimes shooting each other in "friendly fire" incidents when booby traps were set off. Eventually they realized that the Japanese weren't there; under the cover of fog, the Japanese had brilliantly evacuated their entire garrison, sneaking 5,000 men past the navy blockade in just fifty-five minutes.

The American strategy for winning the Pacific war was to advance on Japan from three directions, east, south-southeast, and southwest:

1. East: Led by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, this task force cleared out the central and north Pacific, capturing one island at a time in a strategy called "island-hopping." In a few cases, like Truk in the Marshall Islands, an island would be bypassed if fierce resistance was expected, but still each battle tended to be tougher than the last, as the Americans got closer to Japan itself. Finally in early 1945 they captured Iwo Jima and Okinawa, from which they began bombing the Japanese homeland.

2. South and Southeast: From his base in Australia, General MacArthur began the rollback of the Japanese with an amphibious landing on Guadalcanal, the southernmost island that had been captured, in late 1942. Next he advanced up the chain of the Solomon Islands, using the same island-hopping strategy as Nimitz. Along the way he had the help of the US Third Fleet in the south Pacific, commanded by Admiral William Halsey, and Australian soldiers assisted in the two-year campaign to recover New Guinea. Once this was done, MacArthur began the work of liberating the Philippines, thereby keeping the promise he had made to the Filipinos, when he left those islands two and a half years earlier ("I shall return"). However, the size of the Japanese garrison in the Philippines, the amount of land involved, and the rugged jungle terrain, all combined to tie down MacArthur's advance; he did not continue on to Japan, because he was too busy rooting out the Japanese from that archipelago for the rest of the war.

3. Southwest: From the start, the Allied campaign in Burma was a cooperative effort, involving Americans, British and Chinese. This front didn't see as much activity as the others, because both sides had a hard time moving in Burma's rugged jungle terrain, and because neither side considered this front very important. The lack of attention and supplies meant that the Japanese waited until March 1944 to attempt an invasion of India from there, and after it was turned back, the Allies moved into this former British colony very slowly. By the end of the war they had recovered the most important cities, Mandalay and Rangoon, but had not even reached the frontier of Thailand.

In some ways the 1944 presidential election was a repeat of 1940. Roosevelt had no trouble getting nominated for a fourth time, and again his message was a variation of Lincoln's "Don't swap horses when crossing a stream." As FDR put it, in 1933 the United States was very sick economically, so "Doctor New Deal" was called in. Under the doctor's care, the patient got better, but then he was caught in a bad accident called Pearl Harbor. This required a different kind of specialist, "Doctor Win-the-War," and he had been taking care of the patient ever since. And yes, it was only a coincidence that the two doctors happened to look alike.

In the Republican camp, Thomas Dewey ran again. Since his last run for the White House, he had become governor of New York, so this time he had the executive experience that he needed to be seen as a serious candidate. However, his platform was much like that of Wendell Willkie; he pointed out that it took a war to make jobs under the New Deal, but that didn't mean he would do away with the New Deal completely.

The New Deal had become a political liability, but neither party saw a way to do without it, so both candidates preferred not to talk about it. The main issue became Roosevelt's health, because he was obviously old and ailing by this time. Roosevelt tried to calm fears about that by telling jokes, but it did force him to choose a new running mate. Several high-ranking Democrats grew concerned that he wouldn't be able to complete a fourth term if he won again, and they didn't want someone as liberal and unpredictable as Henry Wallace taking his place, so they urged him to pick somebody more moderate, like Senator Harry S. Truman of Missouri. Although FDR still liked Wallace, and didn't know Truman very well, he agreed to do it. This decision would have fateful results after the election.

The Republicans responded by accusing the Democrats of corruption (one story claimed that FDR sent a warship to Alaska to pick up his dog Fala), and of being too friendly with big-city political machines and communists. However, it was war news that decided the election. In 1944 most of the war news was good, so most voters felt that victory was certain if they stayed the course. The result was that Dewey got 12 states and 22 million votes, but Roosevelt's 36 states and 25 million votes won.(17)

We noted in Chapter 4 that no president had traveled abroad before the twentieth century. FDR was the first to do it in wartime, and his contribution to the war effort was to become a roving commander, meeting with as many other Allied leaders as possible. In January 1943 he flew to Casablanca, Morocco, where he met with Churchill again and the two leading generals of the Free French, Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle. Here they announced that their ultimate goal was the unconditional surrender of Germany, Italy and Japan. Churchill came to Washington in May to plan the war's Italian campaign with Roosevelt. Then in August another strategy session was held in Quebec, Canada, this time between Roosevelt, Churchill and the Canadian prime minister, William Lyon MacKenzie King. Roosevelt went to Cairo in November for the "Big Four" summit with Churchill, Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang Kai-shek. Immediately after Cairo came the first "Big Three" conference in Tehran, where Roosevelt finally got to meet Joseph Stalin; Roosevelt and Churchill promised to launch a second front in France in 1944, and Stalin agreed to start up a new Soviet offensive at the same time. On the way back from Tehran, Roosevelt and Churchill stopped in Cairo again, to meet with the president of Turkey, Ismet Inönü. A second Quebec conference was held by Roosevelt and Churchill in September 1944, to begin planning what to do with Germany after the war. Behind the scenes, representatives of 39 Allied nations met at Dumbarton Oaks, a mansion in Washington, D.C., in late 1944 to organize the United Nations; in the long run, this was probably as important as the more visible summits. Finally, there was a second "Big Three" conference at Yalta in the Crimea (February 1945), where Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin worked out their final plans for the defeat of Germany, their postwar Europe plans, and set the date for the first United Nations conference; Stalin also promised to go to war against Japan. After Yalta, Roosevelt took a yacht to the Suez Canal, where he met Egypt's King Farouk, Ethiopia's Haile Selassie, and Ibn Saud, the first king of Saudi Arabia. The meeting with Ibn Saud was recognition of the importance of the oil discovered in his kingdom, just a few years earlier.

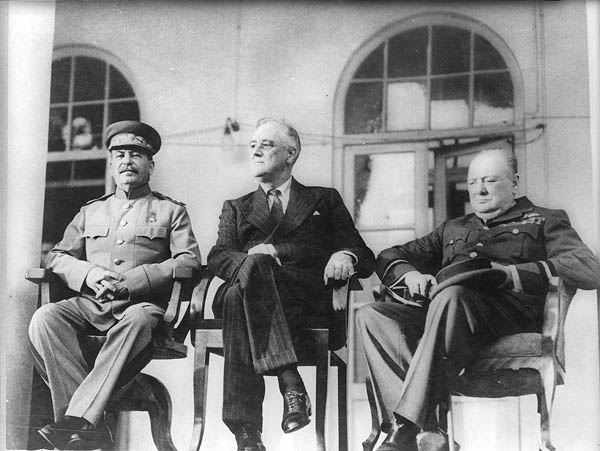

The "Big Three" in Tehran. . .

And at Yalta.

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES

1. Indeed, the desperate situation created by the Great Depression prompted passage of the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution, which moved inaugurations from March 4 to January 20, thus shortening the interregnum between presidential administrations from sixteen weeks to ten. Congress ratified it on January 23, 1933, even before Roosevelt was sworn in, but it did not go into effect at that time, so Roosevelt's second term was the first to begin on January 20.

2. To the casual observer, the AAA's policy of reducing the supply, or even destroying crops, looked like pure foolishness, especially since many Americans at the time did not have enough to eat. Roosevelt's Secretary of Agriculture, Henry A. Wallace (the son of Henry C. Wallace, Harding's secretary of Agriculture), may have been the most leftist Cabinet member in US history; he believed it was no longer safe to let farmers raise and sell whatever they wanted, and that the Soviet Union's planned agriculture was the way of the future. His most unpopular orders called for slaughtering six million pigs and plowing under ten million acres of cotton. The only way to defend the AAA was to argue that raising the price of crops was more important than increasing the supply. Wallace asserted this was no different from a factory reducing output because too much of its product already existed on the market. We haven't experienced deflation since the Depression years, but we can see those practices today; not only does the government still pay farmers to leave part of their fields fallow, but it may keep the prices of their products artificially high by buying surpluses, which are later given away or simply thrown away.

3. The first chairman of the SEC was Joseph Patrick Kennedy, a prominent businessman. He had made his fortune selling liquor and real estate. Later on there were rumors that he had imported liquor during the Prohibition years, and when somebody asked Roosevelt why he put an alleged crook in that job, he answered, "Takes one to catch one." The rumors were never verified, though. They now appear to be exaggerations of what he did regarding Prohibition. Right before it became illegal to sell liquor, the elder Kennedy stockpiled an emergency supply of whiskey (something you'd expect an Irishman to do), and when he heard that Prohibition was about to end, he imported some of the more fancy brands of gin, and kept it sealed in warehouses until the repeal took place. In both cases he did not resell the liquor while Prohibition was in effect, so his actions were technically legal. Then in the 1940s, Roosevelt made Joe Kennedy his ambassador to Great Britain.

4. Social Security was inspired by Francis Townsend, a California physician who proposed giving a $200/month pension to the nation's elderly, which would be paid for by a 2% sales tax. Millions of Americans endorsed the idea, prompting Roosevelt to come forward with his own proposal.

5. After becoming president, Franklin Roosevelt invited Huey Long to a lunch with his family. Long had a reputation for wearing gaudy outfits; once when he was governor and staying in a New Orleans hotel, the captain of a German ship paid a courtesy visit. Long greeted him in green pajamas, a red-and-blue robe, and blue slippers; one reporter said the Kingfish looked like an "explosion in a paint factory." For the luncheon he wore a loud suit, pink necktie, and orchid shirt. This prompted Roosevelt's mother to ask, "Who is that awful man sitting next to my son?" Long kept quiet, but later remarked, "By God, I feel sorry for him. He's got even more sons of bitches in his family than I've got in mine."

6. Maine had a reputation for picking the winners of presidential elections, leading to the saying, "As Maine goes, so goes the nation." That ended when it voted for Landon in 1936, and Jim Farley, FDR's postmaster general and campaign manager, changed the phrase to: "As Maine goes, so goes Vermont." The day after the election, an anonymous joker put a sign beside a road crossing the Vermont-New Hampshire border which read, "You are now leaving the United States."

7. "By June 1937, the recovery...was over."--Gene Smiley, economic historian, writing for The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

8. Those Americans who could afford it found temporary escape from the problems of the day, through entertainment like movies and ball games. Nowadays the late 1930s are seen as a golden age for Hollywood, because this is when Bing Crosby, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Charlie Chaplin, Shirley Temple, and many other actors made their most celebrated film appearances. Walt Disney did the same thing with cartoons, turning them into animated features like "Snow White." A few of these films were produced in color, but that would not become a common practice until the 1950s. Celebrities in other fields included Dizzy Dean (baseball), Jesse Owens (track & field), Joe Louis (boxing), Benny Goodman (music) and Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck (literature).

9. Woodrow Wilson found the Bolsheviks detestable; he and his Republican successors tried to undermine the Soviet Union, in the hope that the Russians would topple their government and install one more to the tastes of the West. By the time FDR came along, this policy had been in effect for a decade and a half, without results. Therefore he declared it a failure, and replaced the proverbial stick with a carrot. In November 1933 the United States granted diplomatic recognition to the USSR; the idea now was that improved relations would encourage the Soviets to act more moderate, and make profitable trade agreements with the outside world. Instead, Stalin continued to brutally lift the USSR into the modern world by working his people to death, and his notorious purges occurred a few years later.

10. The "no third term" tradition became law in 1952, with passage of the Twenty-second Amendment to the Constitution. By this time the Democrats had controlled the White House for nineteen years, so as you might expect, most of the amendment's support came from Republicans.

11. During the Depression years, some Americans were attracted to the governments of foreign nations that didn't seem to be suffering as much. Leftists, for example, had been fascinated with the Soviet experiment since Lincoln Steffens, a muckraking journalist, visited the USSR in 1919 and came back saying, "I have been over into the future - and it works!" The Soviet Union was largely unaffected by the Depression because almost nobody wanted to trade with it. The image of communism was also helped by reporters like Walter Duranty from The New York Times, who denied that Stalin was starving millions of Ukrainians in order to make his first "five year plan" a success. Meanwhile in the US, the American Communist Party (CPUSA) saw its membership grow while the Depression continued. To the communists, Roosevelt was a "tool of Wall Street," Norman Thomas, who had replaced Eugene Debs as the perennial Socialist candidate for president, was a "social fascist," and John Lewis was a "labor faker." Regarding World War II, they followed the party line at first, arguing that the war was simply a conflict between rival imperialists that did not concern the workers. Hitler's invasion of the Soviet Union changed that point of view in a hurry!

On the right fringe, an American Nazi party called the German-American Bund sprang up. Most of its members had German ancestry, and while the group was not controlled by or officially sanctioned by the Nazis in Germany, it looked a lot like the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth), the organization set up to indoctrinate young Germans and train them for war. The Bund's main activity was camping, where the participants would march around in military drills, and practice with rifles. Of course, most Americans found Hitler no more appealing than Lenin and Stalin, and these Nazi summer camps gave the neighbors the creeps. The Bund immediately went out of business after the United States entered the war; the camps were closed, and Julius Kuhn, the German-born Bund leader, went to prison for tax evasion and embezzlement (no, I don't know if he met Al Capone there).

When it came to demagogues, Americans always preferred the home-grown kind. We saw one of them already, Huey Long. Others included Father Charles Coughlin, a priest who used radio to promote Hitler and anti-Semitism, until his superiors in the Catholic Church ordered him to get out of politics; and Gerald L. K. Smith, the leader of the America First Movement. And Henry Ford, the automobile tycoon, was an anti-Semite and an open Nazi sympathizer; the German branch of his manufacturing empire was called Ford-Werke. After the war started, Ford-Werke built military equipment instead of cars, and it used the forced labor of POWs. Nevertheless, Ford continued to do business with Hitler until August 1942, eight months after Germany declared war on the United States.

12. Denmark had fallen to the Nazis in April 1940, and one month later the British occupied Iceland, then part of Denmark, to keep it out of German hands. The other Danish colony in the north Atlantic, Greenland, agreed to allow a US occupation force in April 1941. In July 1941 American troops also went to Iceland, freeing up the British to defend their home shores. The temporary presence of all these foreigners created enough jobs to guarantee total employment on Iceland and Greenland during the war years; at its peak, the occupation force on Iceland numbered 40,000, exceeding the adult male population!

13. Go to http://wyolife.com/KerryFest/WWII%20Actors.htm for a list of actors who served in World War II. You'll be impressed by the names you recognize.

14. However, the Japanese-Americans living in Hawaii, where they made up a third of the population, were left alone, even though a few of them turned out to be Axis sympathizers (e.g., the Niihau incident). Also, 17,600 Japanese-Americans proved their bravery and loyalty by serving in the armed forces during the war, mainly in the European theater. One of them was a future senator, Daniel K. Inouye, who lost an arm as a result of injuries suffered during the Italian campaign. Most amazing of all, 1,200 of those soldiers were volunteers from the internment camps, who enlisted to clear their names. That they definitely did; two Japanese-American units, the 100th Battalion and the 442nd Regiment, were the most highly decorated American military units of all. After the war, President Harry Truman told a delegation of solders from the 100th and 442nd, while giving them their seventh presidential citation: "You fought not only the enemy but you fought prejudice - and you have won."

15. The historian Andrew Roberts calculated that of the 4,572 Allied servicemen who died on D-Day, more than half--exactly 2,500--were Americans. Of the rest, 1,641 were British, 359 were Canadian, 37 were Norwegian, 19 were French, 13 were Australian, two were New Zealanders, and one was Belgian.

16. A reporter for Yank magazine discovered this graffiti from an American soldier at Verdun, France:

"Austin White - Chicago, Ill. - 1918

Austin White - Chicago, Ill. - 1945

This is the last time I want to write my name here."

17. Here are two bits of political trivia for anyone interested. First, for the 1944 presidential election, both the Democrats and Republicans nominated candidates from the same state, New York. That would not happen again until 2016. Second, Dewey was the most recent candidate from a major party with any facial hair; remember all the presidents with beards in the late nineteenth century? A comedian named Fred Allen joked about Dewey's mustache by remarking that "Thomas Dewey seemed to be eating a Hershey bar sideways."

It now appears that Roosevelt made a serious gamble with his health, and won, when he ran for re-election in 1940, let alone 1944. According to FDR's Deadly Secret, a 2010 book by Eric Fettman and Dr. Steven Lomazow, FDR was sicker than we thought, and knew he shouldn't run again. In his second term, melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, appeared as a lesion over his left eyebrow. Whatever cancer treatments he was given didnít work, because by 1944 it had metastasized in his abdomen and brain. This caused a blood loss so bad that he required nine emergency transfusions in the spring of 1941, and he suffered several seizures during the last year of his life. Nevertheless, he ran anyway, because he believed he was the man needed to win the war and establish the United Nations. If he had lost one more pint of blood at the time of the tranfusions, Henry Wallace, and not Harry Truman, would have become the next president.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

The Anglo-American Adventure

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|