| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Russia

Chapter 5: SOVIET RUSSIA, PART II

1928 to 1945

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The February Revolution and the Provisional Government | |

| The Bolsheviks Take Over | |

| The Russian Civil War | |

| The Russo-Polish War and the Comintern | |

| The New Economic Policy | |

| The Struggle to Succeed Lenin |

Part II

Part III

| The Cold War Begins | |

| Recompression at Home | |

| The Khrushchev Years | |

| Brezhnev Takes Charge | |

| Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Doctrine & Détente | |

| Gerontocracy Triumphant | |

| Gorbachev's Experiment | |

| The Union of Fewer and Fewer Republics |

The Nightmare of Stalinism Begins

Once Trotsky had become "The Prophet Unarmed," Stalin reversed his previous political stand and put Trotsky's economic program into action. Presenting his plans for the forced industrialization of the USSR, he told his followers: "We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries and we must make good this gap in ten years. Either we do it, or they crush us." It seemed an impossible task, but Stalin went ahead and set ambitious goals for his first Five Year Plan (1928-33). NEP was replaced by strict government supervision of industry and agriculture. The people were made to work hard at low wages and look to the future for their reward. Collective farms were set up, to be tilled jointly by peasants with farm machinery provided by the state. New cities and factories were built on a grand scale, especially in the Ural mts. and Siberia, far beyond the reach of any warplanes from Europe. 20 million people moved from the countryside into the cities to take the new jobs available there. The first Five Year Plan was followed by a second in 1933. Together the plans pushed the USSR into the industrial age and created an exhilarating feeling that all were working together to build a glorious socialist state.

But the cost in human life, freedom and well-being was almost unbelievable. To build a modern state overnight, workers labored long hours for poor pay, lived in cramped, unheated quarters and had to forego things that Westerners take for granted: shoes, radios, sometimes even food. And they had to live with the system whether they liked it or not.

To protest was futile. Stalin and his henchmen brutally repressed whatever real or imagined opposition they encountered. Factories and farms were given production quotas they had to meet; if they failed to do so, the plant or farm manager would be denounced as a "wrecker," "foreign spy," or "imperialist agent"; that failure often cost the manager his job, and sometimes his life. The peasants who did not give up their farms willingly to the collectives were herded into a network of concentration camps called the Gulag, and there the kulaks were ruthlessly liquidated as a class.(8) Even animals suffered as a result of the Five Year Plans; to avoid giving them up to the state, 2/3 of the country's livestock was killed by the peasants.

These brutal methods could not make agricultural and industrial production meet Stalin's goals, but they did get impressive results. Total industrial output increased fivefold under the first two Five-Year Plans. The new blast furnaces at Magnitogorsk and Stalinsk were producing as much iron and steel as the whole country had in 1914, to give just one example. Only the industry of the United States and Germany produced more, and the USSR was rapidly catching up with Germany. Part of this was because of the Great Depression; since the USSR had little trade with the outside world, it was unaffected by the worldwide slump that hit every other advanced nation, allowing the USSR to leap ahead while most of the world economy lay idle.

To justify his actions, Stalin launched a Soviet cultural revolution. Russian art and literature, which had been largely ignored by the state since 1917, now became Stalin's tools of propaganda. The cultural expression of minority groups was suppressed; when Soviet archaeologists found fourth-century artifacts left by the Ostrogoths, they had to invent a new civilization to explain them, because the party line would not have allowed this reminder that a German tribe once ruled the same parts of Russia that the Germans occupied in both World Wars. New history books were written that claimed the Russians invented everything years before the West did, and that the Bolshevik Revolution was the most important event in world history. Plays and movies that Stalin did not like were suppressed for being "ideologically unsatisfactory," and they were replaced by shows that glorified Russian heroes like Alexander Nevsky, Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and Alexander Suvorov; all of them emphasized submission to the state as the best way to stop foreign invasions. Later on, when Stalin had exterminated most of the revolution's participants, he had himself portrayed as the omnipotent and infallible leader, the only man who could finish what Lenin started.

Stalinism reached a new level of absurdity in the field of biology. In 1930 an agronomist named Trofim Lysenko claimed that he had proved through experiments with seeds that plants acquire their characteristics from the environment, not through heredity. Stalin endorsed the theory, thinking it was proof that a Marxist society could produce superior human beings. "Lysenkoism" was taught in the schools, and the teaching of classical genetics was outlawed because it disagreed with Lysenkoism. Lysenko's methods were not objectively tested until 1965, and only then was Lysenkoism shown to be the fraud that it really was.

Stalin dealt fiendishly with political opposition. After Trotsky was gone, the main opponent to Stalin's rule was Sergei Kirov, the young chief of the Leningrad Communist Party since 1926. By criticizing Stalin's heavyhanded tactics at the Seventeenth Party Congress (1934), Kirov immediately became the most popular man in the USSR. At the end of the same year, however, Kirov was murdered by a secret police agent. To cover up, Stalin immediately ordered the assassin and 49 alleged accomplices shot; Zinoviev and Kamenev were charged and sent to prison. Then the accusations became a horrible mass purge that arrested and sent at least half a million "Kirov's assassins" to the Gulag.

When the Kirov affair had reached the limits of excess, Stalin put into motion a series of purge trials in 1936. At the first one he put on trial all sixteen of the Party's highest ranking left-wing members, including Kamenev and Zinoviev. Stalin went back into the past of these men, digging out any "skeleton in the closet" he could find, such as:

1. Did this Bolshevik ever oppose Lenin on anything?

2. Did he ever support Trotsky's point of view?

3. Was he ever a Menshevik?

If any of those questions could be answered yes, Stalin had an open and shut case. Whether or not he did, he would accuse them of preposterous conspiracies, like plotting to kill Lenin, Stalin, and/or Kirov; attempting to sabotage Soviet industry; spying for the capitalist powers; or plotting to hand over the Ukraine to Germany. The defendants were forced to confess to these "crimes," recant, and put the finger on anyone else they might know who had done what they confessed to. The show trial was over in four days, and all the defendants were executed immediately.

This process was followed throughout 1937 and 1938. Stalin's next victim was the army; more than half of the officers, including Marshall Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the Civil War's most popular hero, were liquidated. Then he eliminated the right wing of the Party, accusing his former allies of overzealousness, becoming, as he put it, "dizzy with success" while carrying out the dictator's orders. One of these victims, for example, was Genrikh Yagoda, the police chief who had presided over the first trials; he was accused of supplying false evidence! His successor, Nikolai Yezhov, was so cruel that the purge trials were sometimes known as the Yezhovshchina afterwards. Finally, when the NKVD was the only power bloc left that could oppose Stalin, he purged it of the former purgers, including Yezhov, and filled its ranks with men like the new chief, Lavrenti Beria, who were devoted both body and soul to Stalin.

At the levels below party leadership, the purges grew to mass proportions before they stopped. Any arrest, deportation and/or execution could result in the same thing happening to the victim's family. Even trivial incidents could bring a sentence in the labor camps; it was said that the huge Baltic-White Sea Canal was dug by those punished for telling political jokes. The Eighteenth Party Congress in 1939 was a very subdued one; only one fourth of those who had attended the Seventeenth Party Congress, five years earlier, were still alive now. We may never know the exact number of Stalin's killings; during the Gorbachev years official Soviet figures put the grim total at 15 million. Of these 750,000 were executed in the purges; 6-7 million starved when the entire Ukrainian harvest of 1932 was confiscated and exported, causing a terrible famine; most of the rest were callously worked to death in the labor camps. And in case you were wondering, most of the victims were ordinary workers and peasants who never threatened Stalin’s position. To save his people from the danger posed by Nazi Germany and militarist Japan, Stalin murdered, beat and brutalized them in a reign of terror that even Adolf Hitler would have difficulty matching.

Prelude to World War II

Stalin was greatly concerned about threats from Nazi Germany and militarist Japan. In 1936 Germany formed an alliance with Italy that was called the Anti-Comintern Pact, or the Rome-Berlin Axis; this clearly showed that the Germans regarded the Soviet Union as their ultimate enemy. As Germany grew more powerful and more dangerous during the 1930s, the British and French thought they could keep Hitler in his place by renewing their World War I alliance with Russia. But terribly little was done about this; many Westerners viewed any sort of alliance with "Bolshevism" as a deal with the devil. The resulting Anglo-French deterrent was not very impressive, and this led Stalin to believe that since Germany, France, Great Britain and Italy were all capitalist countries, they might join together to destroy communism, instead of fighting each other.

In the USSR, nobody hated the Nazis more than the Jewish Foreign Minister, Maxim Litvinov, and when Stalin replaced him with the less independent-minded Vyacheslav Molotov in May 1939, Hitler took this as a hint that Stalin was willing to listen to a better offer from the Axis powers. Hitler stopped making anti-Soviet remarks in his speeches, and in August he sent his Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, to Moscow with the following offer: How would Stalin like to have the eastern half of Poland in return for keeping out of the upcoming war between Germany and the West? Stalin, angry and alarmed at the West's attitude toward him and his regime, accepted--with conditions. As well as eastern Poland he asked for, and got, Romanian Bessarabia (modern-day Moldova) and a free hand in Finland, Estonia and Latvia. In return for this he promised to supply the Nazi war machine with whatever raw materials it needed; that promise was kept punctually until the day Germany invaded Russia. Once the non-aggression pact was signed, both sides were elated; at the Kremlin banquet afterwards, Ribbentrop was bold enough to joke that soon the Soviet Union would join the Anti-Comintern Pact! One week later, on September 1, 1939, Nazi tanks rumbled across the Polish border from the west. Britain and France declared war, Russia moved in to grab its share of Poland 16 days later, and World War II was on.

The Winter War

By the first week of October Poland had been crushed between the Nazis and the Soviets. When negotiating with Stalin, the Germans had only talked about taking the western third of Poland; now, because the USSR had delayed its invasion, Hitler had central Poland, too. Stalin did not make a fuss; he just said he would like to have Lithuania added to his sphere of influence as compensation. Hitler agreed and Stalin now went ahead to claim the other areas promised to him. Too weak to resist, the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were pressured into allowing Soviet military bases on their territories.

Next, Stalin turned to Finland, demanding that the Finns abandon their fortifications--some of which were only 17 miles from Leningrad--and pull back to the Russo-Finnish border of 1743-1809. Finland refused, so Stalin, like Hitler had done with Poland, accused the Finns of attacking a Russian town, made another set of unreasonable demands, and when the Finns rejected them, he ordered an invasion, which began on November 30, 1939.

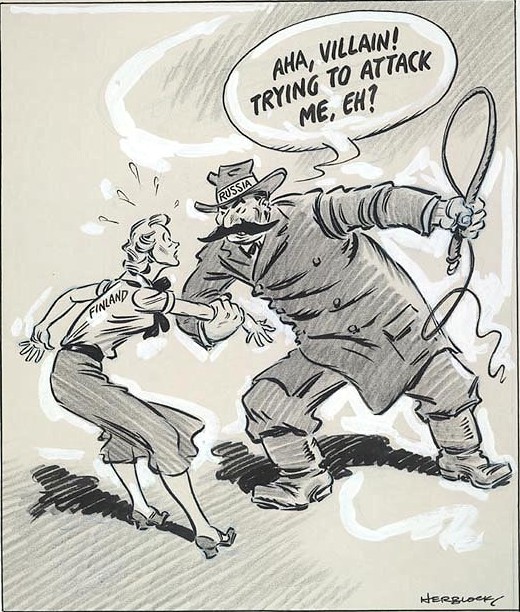

An early cartoon by Herblock made fun of the Soviet claim that Finland started the Winter War.

Naturally Stalin expected the Winter War, also called the Russo-Finnish War, would be a cakewalk for the Red Army, because it outnumbered the Finns in every way:

| USSR | Finland |

| Soldiers at the war's beginning | 450,000 | 180,000 |

| Tanks | 6,541 | 30 |

| Aircraft | 3,800 | 130 |

However, once the invasion got underway, nothing went as planned. To start with, the weather of the season produced temperatures ranging from 0o to -40o F., and snow that could be as much as six feet deep. Russians fight well in the winter, of course, but the Finns fought even better. Wearing white clothing to hide in the snow, and using skis to move quietly, the Finns put up a magnificent resistance, fighting the Red Army to a standstill and inflicting far more casualties than the Soviets inflicted on them.(9) World opinion supported the Finnish underdogs, but because the outside world couldn't get military aid to Finland, their sympathies weren't enough to decide the outcome of the war. Meanwhile, Stalin replaced the commander of the Soviet forces, Marshall Semyon Budyonny, with the more competent Semyon Timoshenko, and threw in enough men and materiel to win by sheer numbers. In February 1940 the Soviets broke through the Mannerheim Line, the defensive barrier the Finns had built between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga; in March the Finns sued for peace. They had to give up the territory Stalin demanded, but by keeping their freedom, they were more fortunate than the peoples of the Baltic states, which by July had been completely absorbed into the Soviet system as the USSR's 14-16th republics.

If Hitler forgot Stalin while he was crushing Denmark, Norway, the Low Countries and France, at the end of June 1940 he got a nasty reminder; that was when the Soviet dictator leaned on Romania, demanding Bessarabia and northern Bukovina. Bessarabia had been promised in the Nazi-Soviet pact, but no one had said anything about Bukovina. Being fully committed against the British, Hitler couldn't do anything except advise the Romanians to submit, but he wasn't at all pleased.

From there Russo-German relations got worse. Both Germany and Russia wanted to have military bases in the Balkans and Turkey, and they could not reach agreement on that. In September Germany, Italy and Japan announced they were dividing the Old World into three "natural spheres of interest": most of Europe would be for Germany, Africa for Italy, and Asia for Japan. It was ominous that Russia was not invited to that meeting, and so were the German troops stationed in Slovakia, Finland and Romania. The last attempt to patch up relations was made in November, when Molotov visited Berlin. At one point during the visit, Ribbentrop proposed dividing up the British Empire between Germany and Russia, because the war against England was really over. Suddenly a massive British air raid interrupted the speech. Molotov asked, "If Britain is finished, whose bombs are falling on us?" There was no answer, and negotiations broke down. By the end of the year Hitler had signed the directive for "Operation Barbarossa," the planned invasion of Russia.

"The Great Patriotic War"

Our narrative is now up to World War II's eastern/Russian front. If you know anything at all about World War II, you know that the war had two major theaters loosely connected together, in Europe and in the Pacific; those conflicts started and ended at different times, and about the only common factor was that the United States and Great Britain were major players in both. This is emphasized by books, movies and TV programs that cover just one front of the war (e.g., the American miniseries "Band of Brothers" was set in western Europe, while a companion miniseries, "The Pacific," looked at battles in the Pacific war). However, the truth of the matter is that World War II was really three wars, not two. The part of the war in eastern Europe, called the Ostfront by Germans and the "Great Patriotic War" by Russians, was by itself nearly as bloody as all of World War I, and in terms of men and equipment committed, and the size of the area fought over, it is certainly one of the biggest wars in recorded history. Of the nearly five million lives Germany lost in World War II, 7/8 of them were lost on the eastern front. The Soviets in turn suffered more than ten million casualties; no other nation could lose that many and still go on to win (the Chinese lost more civilians, but their country and army were so backward and corrupt that they would not have come out on the winning side if they were fighting alone). Yet here in the West, the war between Nazi Germany and the USSR is the conflict we know the least about, despite all the death and destruction, so this narrative can be seen as an effort to give equal time to World War II's third (Russian) theater.

Operation Barbarossa

The non-aggression pact was supposed to last for ten years, but Hitler had no intention of keeping it any longer than necessary. In late 1940 and early 1941, Hitler massed 154 German, Finnish, Hungarian, Romanian and Slovak divisions along the Soviet frontier. Meanwhile the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, went to work on his plan for turning the Mediterranean Sea into an Italian lake by invading Greece (from Albania) and Egypt (from Libya). Both offensives quickly became embarrassing routs; by the spring of 1941 he had lost half of Libya and all of Ethiopia to the British, and a third of Albania to the Greeks. Mussolini called upon Hitler for help, and the German forces diverted to the Balkans and Libya did their job, but this also made Hitler postpone Operation Barbarossa for five weeks. Those turned out to be five critical weeks; they kept Hitler's panzers (armored divisions) from capturing Moscow before summer ended. By putting the Nazi flag on the Acropolis (see below), Hitler passed up his best opportunity to drape it over the Kremlin.

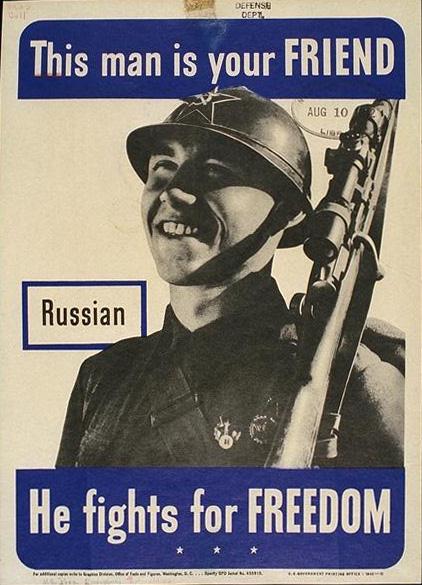

Paranoia was a strong motivator for Stalin, so it is amazing that he trusted Hitler, one of the least trustworthy leaders of modern times. When warned of the Axis buildup in the west; he did not see it as a threat; he even fooled himself into thinking that the Axis troops were using the wide-open spaces of eastern Europe to train for an invasion of Britain. During the last days before the invasion, German aircraft flew hundreds of reconnaissance missions, and German deserters crossed the border, warning that Germany was preparing for war with the USSR; Stalin refused to believe these warnings, arrested and "questioned" (meaning tortured) the deserters, and shot one for spreading false information. Therefore, when Hitler launched the onslaught on June 22, 1941, Stalin's surprise was total. For eleven days the "man of steel" was not seen, as he kept himself in shocked, near-catatonic isolation from almost everybody; he may have been drunk during this time. The British had mixed feelings about their new ally; anyone fighting Hitler was welcome, but Stalin had behaved shamefully up to this point. Nevertheless, a portion of the American military aid ("Lend-Lease") that had been sent to the British was soon going to the Russians as well.

The Axis forces were organized into three groups: Army Group North in East Prussia, Army Group Center in Poland, and Army Group South in southern Poland, Hungary and Romania. After crossing the Soviet frontier, Army Group North advanced toward Leningrad, Army Group Center repeated Napoleon's march on Moscow, and Army Group South drove on Kiev; all used the blitzkrieg tactics that had been perfected in Poland and France. The Soviet forces were always numerically superior, but they were strung out evenly along a 1,200-mile front, and thanks to the purges, were commanded by leaders chosen for their loyalty rather than their competence; the southern commander, for example, was Marshall Semyon Budyonny, who we last saw botching up the campaign against Finland in 1939. For this war, Budyonny topped his previous performance by refusing to use tanks, insisting that charges by men on horseback were still the best way to win battles; if you know anything about the German panzer divisions, I don't have to tell you how that worked out. The northern commander, former Defense Commissar Kliment Voroshilov, was hardly better, and only Semyon Timoshenko (the general in charge of the central front) showed enough skill to inspire any hope. Most of the generals feared Stalin so much that they would not withdraw to safer lines of defense. This gave the Germans a fabulous initial opportunity, and they seized it; Army Group North advanced fifty miles on the first day! On the central front, two pincer movements surrounded first Minsk, then Smolensk, capturing 348,000 Russian prisoners in the first month of the campaign.

The peoples living in the areas captured by the Germans welcomed them as liberators from Stalin. Many of them were non-Russians like Ukrainians, Byelorussians, and Lithuanians; recent events like the Ukrainian famine meant they never liked Stalin in the first place. Unfortunately for them, Hitler did not respond accordingly; to him all Slavs were untermenschen, inferior creatures only fit to be slaves of the master race. Before the war he had talked about Germany's need for lebensraum (living space), so his ultimate goal was to kill millions of Slavs, to make room for the Germans he planned to move there. Three million Slavs were put to work in German mines and factories, where they were treated like subhuman creatures. All Soviet commissars were shot on sight. As persecution of the eastern Europeans, particularly the Jews, increased, Soviet citizens realized there were no good guys in this war; their only choices were two forms of oppression, one bad, the other worse. A full-scale partisan movement developed, starting with the Red Army soldiers caught behind enemy lines. Their campaigns of sabotage, assassination, etc., seriously hampered the Axis war effort, and encouraged resistance to stiffen in those areas still under Soviet control. A "scorched-earth" policy was practiced, where the Russians burned or blew up everything that was likely to fall into German hands. After the war, surviving German generals wrote that if they had really been liberators, they could have teamed up with the USSR's citizens to topple communism, and that was probably the biggest reason why they lost the war.

Stalin sensed all this and when he appeared in public again, he did not talk about Marxist ideals. Instead, he called upon the Russians to defend the "Motherland" in patriotic terms, using heroes of the past like Alexander Nevsky and Dmitri Donskoy (see Chapters 2 & 3) as examples for their descendants to follow. Religious persecution was reduced, to win the support of the Orthodox Church; the Church was allowed to have a patriarch (the first since 1700) and own property again.

Though the Germans were doing great in the summer of 1941, there were some ominous signs that the war would not remain a cakewalk for them:

1. Their goals were set impossibly high. Russia's performance in World War I and the recent Russo-Finnish War led Hitler to believe that the Wehrmacht would have no trouble blowing away hordes of Red Army soldiers. Therefore, the Germans expected to take everything west of a line drawn from Archangel to Astrakhan (from the Arctic to the Caspian Sea) in six weeks, but nobody could do that. In fact, they did not capture any of their important objectives until Kiev fell in September. Meanwhile, Soviet factories were dismantled and moved to the other side of the Urals, meaning that the USSR could lose its western territory and still fight on.

2. Losses were high, too. Though the Germans had everything going their way, they still lost more men in the first weeks of the campaign than they had lost in Poland, Norway, the Low Countries and France combined.

3. The Soviets had caught up. The Germans were still ahead in organization and technology, but the difference between the armies was not as great as it had been in World War I. The best examples of how the gap had closed were a medium Russian tank, the T-34, and a heavy tank, the KV-1; both were good enough to stand up to Hitler's armor.

The Germans display some captured T-34 tanks, in the winter of 1943-44.

4. The army of Soviet Russia did not fight like the army of Tsarist Russia, and only gradually did the Germans realize it. Nor did it fight like the other Allies. Whereas the Poles, French, Belgians, British, Americans, etc. would resist for a while and surrender when they knew their chances were hopeless, the Russians didn't seem to know when to quit, and usually fought ferociously to the last man. Often Russian women fought alongside the men as well; this was a big surprise to the Germans, who kept their women at home. Russian women served exceptionally well as snipers and Red Air Force pilots; the latter earned the name "night witches" from the Germans, because their favorite tactic was to bomb German positions at night and cut their engines shortly before dropping their bombs, so that the Germans on the target would not hear them coming.

Hitler was more interested in the resources of the south (grain and oil) than he was in Moscow and Leningrad, so on August 9 he made an important intervention, which halted the German advance on the northern and central fronts. At this stage, one more push by Army Group North would have reached Leningrad, but instead that army was ordered to blockade the former capital, killing as many of its residents as possible, before taking it. Hitler may have felt that feeding Leningrad's large population would have been a burden for Army Group North. Whatever the reason for his decision, it kept Leningrad in Soviet hands, but for 900 days it endured what may be the most horrifying siege of any city in modern times; here cannibalism became a common survival tactic.(10) As for the panzer divisions, those from Army Group North and half of those from Army Group Center were ordered to strike south. They met the southern units 150 miles east of Kiev, trapping 600,000 troops. The whole Ukraine passed under German occupation.

Greatly elated by this victory, Hitler resumed the offensive on Moscow. Army Group Central's tanks broke through the first of three defense lines around Moscow, surrounding 45 divisions. The second line was carried almost as easily. The fall of Moscow looked so certain that the Soviet government moved to Kuibyshev (modern Samarra), 550 miles to the southeast; Stalin, however, chose to stay until the end. With more panzers racing up from the south, the envelopment of Moscow appeared to be proceeding satisfactorily, but now it was October. On the very first day of the Moscow offensive, the first snowflakes of winter fell. Most Russian roads between the cities were unpaved, with a notorious reputation for turning into mud when it rains in the spring and fall; this time, the fall rains bogged down foot soldiers, wheeled and even tracked vehicles. In addition, supplies were failing to get through, and the troops were exhausted. The best Soviet general, Georgi K. Zhukov, took charge of Moscow's defenses, and he brought in 40 fresh divisions of reinforcements from the Far East; those were now available because Japan and the USSR had signed a neutrality agreement in April. Winter immobilized the panzers with -40o weather that froze important pieces of equipment, split engine blocks, and made engine oil as thick as tar; sometimes fires had to be lit next to trucks and tanks in order to start their engines. The Germans had expected in be in Moscow by the end of summer, and still wore summertime uniforms; now there were stories of them adding layers of newspaper under their clothing, or stealing the heavier uniforms off the enemy dead, in order to keep warm. Finally the Soviets, especially the Siberians, were temperamentally better suited to cold weather, because they had to endure it every year. The Red Army introduced divisions of cavalry, which suffered frightful losses, but had the advantage in mobility while the tanks could not move. Swords, bayonets and grenades were the only effective weapons in this weather, and the Russians were better-trained in this hand-to-hand fighting than the Germans. At the gates of Moscow, the Red Army became the first army to stop a blitzkrieg.

Stalingrad: The Turning Point

By December 1941 the USSR had lost 2,500,000 men, more than three times as many as Germany, but it still had a tremendous supply of manpower in reserve. Because the Germans had reached the limit of their endurance, every one of Hitler's generals advised him to withdraw and regroup. Hitler would have none of this; anyone who suggested that he give up an inch of conquered territory was a traitor in his book, so he sacked the commanders who refused to obey his stand-still orders. Convinced that the victories of 1709 and 1812 were about to be repeated, Stalin ordered an all-out offensive on December 6 that pushed the Germans back from Moscow, and thrust alarming-looking salients into the central front. But the arms of that pincer movement, which were supposed to meet at Smolensk, were held apart by Army Group Center's panzer divisions, and the Russian paratroops landed near Smolensk in a last-ditch attempt to close the gap were not strong enough to do the job. Even so, some Russian forces had advanced ninety miles, and in the south, the city of Rostov-on-Don had been recovered only a few weeks after the Germans captured it. These minor successes encouraged Stalin to expand the offensive, though now his commanders were warning him that the drain on Soviet resources was immense. Instead of listening, he ordered new attacks to relieve Leningrad and Sevastopol; both failed, resulting in a loss of 100,000 men. They did succeed in isolating seven German divisions in the north, at Demyansk, but Hitler merely laughed this off and ordered his planes to keep Demyansk supplied, until ground forces could come to the rescue next spring. The surrounding Russians could not prevent either the supply or the rescue attempt.

Stalin was forced to admit that it would take a long campaign to get the Germans out of Russia. But when the weather warmed up in April 1942, he failed to see that it was now his turn to pull back. The first German offensive of the year cut off the Russian salients; the Russian gains, which had looked so menacing during the winter, now became death traps. Soviet losses for May and June exceeded three quarters of a million men; for anyone who thought that the Nazis would be quickly shoved into the garbage can of history, it came as a rude shock.

Hitler chose to be more cautious in the 1942 campaign. Rather than make a second attempt at Moscow, where the Russians now had most of their armor, he went for a purely economic objective, the oilfields of the Caucasus. One half of Army Group South would be used to drive the Soviets behind a line stretching from Voronezh to Stalingrad(11), while the other half would make a beeline for Azerbaijan. The first part of the operation, in July and August, followed the German plan perfectly; Russians called this period "the black summer," and a Soviet collapse looked likely. But the river and rail connections between the Caucasus and the rest of the USSR ran through Stalingrad, meaning that the Germans would have to conquer that city to isolate the areas to the south. By the time Hitler noticed this, a Russian army had moved into Stalingrad, ending all chances of taking it easily. Stalingrad had to be fought for street by street, and since Russian reinforcements came across the Volga every night, the Germans were soon measuring their daily gains in yards, counting their casualties in the thousands, and turning the entire city into rubble. This type of attrition, which had been so common in World War I, was deadly to an army that had shown the world how to win by moving fast. Yet Hitler would not give up; he sent division after division into Stalingrad. Germans on the front line called Stalingrad "the Cauldron," because it consumed men as fast as they could be committed. As for the Russians, they would not be driven out even when their backs were against the Volga.

Most of the German reinforcements for Stalingrad came from the army in the Caucasus, which had gotten halfway to Baku by this time (it halted just short of Grozny, in Chechnya). The Germans never had enough men to capture Stalingrad and the Caucasus at the same time, and now the offensive stalled before it had gained complete control of either. In fact, the demands of Stalingrad meant that only the most important points on the front had any Germans at all. Elsewhere the gaps were reluctantly filled by a mixture of Italian, Hungarian and Romanian divisions. The Wehrmacht even resorted to recruiting Soviet citizens, ignoring Hitler when he told them he didn't want untermenschen in the army. By the end of 1942, there were three million Axis soldiers on the Russian front, and 700,000 of them were ex-Soviets. When the Russian counterattack came on November 19, it struck the two Romanian armies stationed just north and south of Stalingrad; both crumbled so rapidly that the Russian forces joined hands four days later, surrounding a quarter of a million Germans in Stalingrad itself.

Whatever chance the German Sixth army had of breaking out of this trap, Hitler now threw away. He refused to allow a retreat while the Soviet cordon was still weak enough to break through ("I am not leaving the Volga!"), and ordered it to stand fast until a relief army came to the rescue. But before the rescuing forces could get there, General Zhukov launched a second pincer attack. Faced with a second envelopment of the same proportions as Stalingrad, even Hitler saw the light. For the first time in the war, orders to pull back to defensible lines were permitted. As a result, in December and January everything east of the Don River was abandoned.

Nothing could be done for the men trapped in Stalingrad. They fought until February 2, 1943, when the 91,000 survivors finally surrendered. Among them, only 5,000 lived to see the Fatherland again.(12)

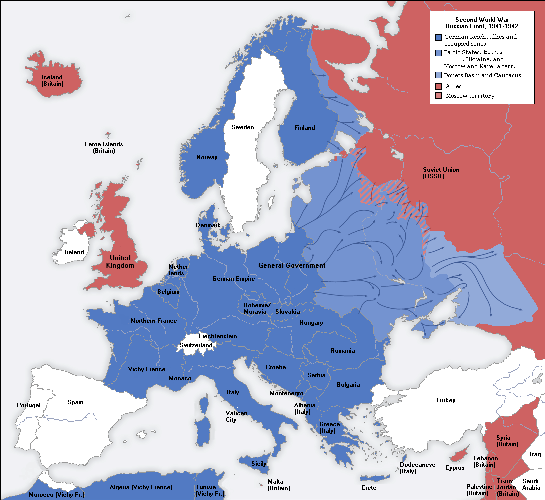

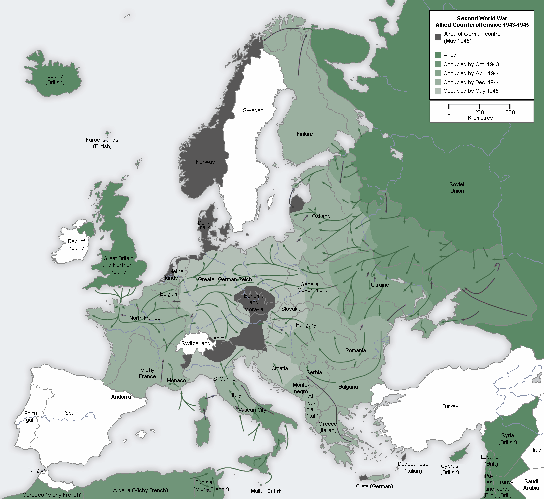

World War II: the Axis strikes. Click on the thumbnail for a full-sized map (214 KB, opens in a separate tab). The dark blue areas represent what the Axis countries ruled in June 1941. The medium blue area was conquered by Germany in Operation Barbarossa. The blue-red striped area was also conquered, but the Soviets recovered it by April 1942. The light blue area was conquered and lost by Germany in 1942. From Wikimedia Commons.

The Battle of Kursk

While the battle of Stalingrad was at its height, General Zhukov launched a counter-offensive on the central front, at Rzhev (Operation Mars, November-December 1942). Though Rzhev was in an exposed position, fog and snow forced the Red Army to go without air support, and the Germans held their ground, inflicting very heavy casualties in the process. Even so, this successful defense was no compensation for the disaster at Stalingrad, and the latter made Hitler listen to his generals. When they warned him that they would not be able to hold onto Demyansk and Rzhev, should the Russians try to take them again, he allowed the evacuation of those cities, one year after Demyansk had been defended with such determination. This freed up enough troops to secure the rest of the north and central fronts, except around Lake Ladoga; there the Russians pushed along the southern shore, giving some relief to Leningrad.

However, Hitler still was not going to concede any losses in the Ukraine. In mid-February 1943 the Russians captured the Ukrainian city of Kharkov (modern Kharkiv). Hitler personally flew to the war zone and ordered the commander of Army Group South, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, to take Kharkov back, though he gave Manstein freedom to conduct the operation as he saw fit. Fortunately for Manstein, the Russians had overextended themselves, and they underestimated the strength and skill of the Germans, even when in retreat. This allowed him to concentrate German forces for a brilliantly timed offensive that took the cities of Kharkov and Belgorod in late February-early March. The 1943 battle of Kharkov was the last German victory in the war, and it put the front lines back where they had been in the spring of 1942.

Once the German generals had tidied up a desperate-looking situation, Hitler ordered an extraordinary amount of men and supplies sent east, to make up for the previous year's losses. They still held the cities of Orel and Belgorod, and the plan for the 1943 summer campaign was to capture Kursk, a Russian-held city between them. If they took out the "Kursk salient," it would rip a hole between the central and southern Soviet armies, and the Germans would have the critical breakthrough they needed. For this task seven panzer divisions were assembled at Orel, and six panzer divisions were grouped at Belgorod. The Russians also knew that Kursk was vulnerable and massed thousands of guns, tanks and defensive barriers, and 1.3 million soldiers, within a 65-mile radius of the city; in the sectors where the attack was expected, there was an average of 4,000 landmines per square mile. Unlike the summer campaigns in 1941 and 1942, this time the Russians had their forces in the right place; it was the ultimate defense-in-depth strategy.

The largest land battle of World War II began on July 4, 1943. The panzers fought their way steadily, but the deepest they could penetrate Soviet defenses anywhere was twenty-five miles. German casualties were very heavy (1,000 tanks and 200 planes were lost on the first day!); the Soviet losses were even heavier, but they, unlike the Germans, still had the reserves to replace them. Eight days after the battle started, Hitler called the offensive off. He claimed that the Wehrmacht was needed elsewhere; although this was true, he wouldn't have canceled a successful operation. Stalingrad meant that Germany could not win the war; Kursk guaranteed that Germany would lose.

The place where German troops were needed was the Mediterranean, where things had been going badly for a long time. A few months earlier a combination of American, British and Free French forces cleared the Axis out of North Africa, and at the height of the battle of Kursk the Allies landed on Sicily, as a prelude to an invasion of the Italian peninsula. Soon after that the Italians jailed Mussolini and announced they wanted to join the Allies; Hitler was forced to occupy Italy to keep it on his side.

Though his forces got considerable relief, Stalin was not impressed with the Allied victories in the Mediterranean. There were still 200 German divisions on Russian soil and what happened to the odd ten deployed elsewhere mattered little to him. When Winston Churchill visited Moscow in 1942, Stalin gave him a good dressing down, asking him questions like, "When are you going to start fighting? Are you going to let us do all the work?" What he wanted to see was an Anglo-American invasion of France that would force Germany to divide its forces equally between east and west. The Americans agreed that this would be the quickest way to win the war, but they did not have enough troops in Europe yet to fight on this sort of scale, and the British were very reluctant to take part in a campaign where they would have to provide more than half the men. Remembering the long casualty lists of World War I, the British instead proposed the attack on Italy, which Churchill called "the soft underbelly of the Axis beast." Rather unhappily, the Americans agreed to go along with this plan.

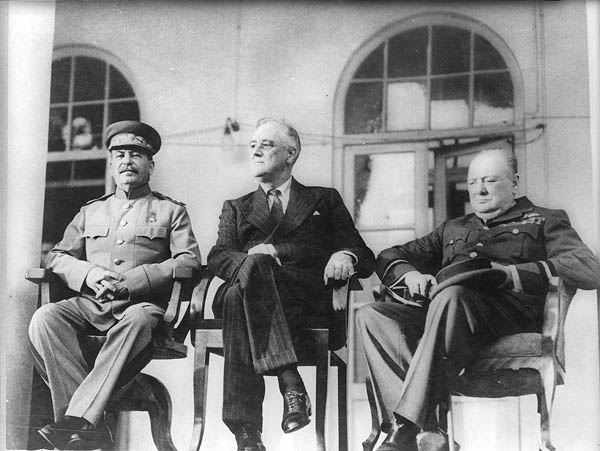

To avoid misunderstandings in the future, Churchill and Roosevelt met with Stalin in Tehran in September 1943. Stalin's victories were the most impressive to date, allowing him to negotiate from a position of strength. It was here that he got his allies to promise a cross-channel invasion of the European continent in 1944.(13) He also proposed annexing eastern Poland and compensating the Poles with German territory; in return he promised to help Roosevelt against Japan, and to cooperate with the new international organization Roosevelt was setting up (the United Nations). On most of these proposals the details were set aside to be worked on in future conferences.

From left to right: Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill in Tehran.

Crushing the Third Reich

Hitler had hoped to wage a successful defensive war in Russia until he could achieve a victory somewhere else, but more things went wrong as soon as the Kursk offensive was called off. The Russians counter-attacked in the two areas the panzers had struck from, recovering Orel and Belgorod on August 4-5, and Kharkov on August 23. A second wave of attacks began to push back the Germans on the central front (Smolensk was retaken on September 25), and cleared out the Taman peninsula in September-October, where a German army had been isolated since spring. The Germans made an orderly retreat from the Donets to the Dnieper River, but Red Army units began crossing the Dnieper on September 22, meaning that for Army Group South, holding the Dnieper would be no easier than defending the Donets. Stalin was determined to get the Germans out of the Ukraine and he committed every man and gun he could muster to achieve this objective. The Russian assault to take back Kiev began on November 3, 1943, and the last Germans were driven out by December 6. Throughout the following winter, Stalin launched one division after another across the Dnieper to keep the Germans retreating. By March 1944 he had cleared out the entire Ukraine and had Red Army troops just across the border in Poland and Romania.

To the north, three Soviet armies attacked the German positions around Leningrad in January 1944. By January 27 the Moscow-Leningrad railway had been secured, thereby ending the long siege of Leningrad. Another Soviet army liberated Novgorod at the same time, and in February these armies worked together to sweep the Germans from the Russian territory north of Smolensk. By March 1, Army Group North had been driven into Estonia and Latvia. Then the Russians turned their attention to Finland; in June they began an offensive against the Finnish trenches near Leningrad and in Karelia (see footnote #10). This part of the war zone had been quiet for so long that the Finns were hoping the Russians would ignore them until they were done with the Germans. Instead, the Russians recovered more than half of Finland's gains from 1941, including the city of Vyborg, before the Finns fought them to a standstill along new defensive lines (the battle of Tali-Ihantala, June 25-July 9, 1944).

The only disappointment in the Red Army's performance was its failure to grip and destroy any large German units, because Stalin insisted on attacking everywhere at once. This strategy kept Army Groups North and South on the run, but it also meant that none of the envelopments were strong enough to hold what they captured; time and time again apparently doomed German units fought their way out of traps and withdrew to safety. Soviet plans for the summer of 1944 showed that this point had not gone unnoticed; the pincer movement on the central front was both simple and strong.

The campaign to liberate Belarus began on June 22, the third anniversary of Hitler's invasion of Russia. It started with pincer movements to surround Vitebsk and Bobruisk, two towns 150 miles apart that Hitler had overgarrisoned. Once both were cut out of the German line, the Russian tanks converged on Minsk in a great pincer attack that enveloped most of Belarus. On July 4 they reached Minsk, and they proved to be strong enough to keep and crush what they held. It was a staggering haul; Army Group Center, desperately trying to re-form in eastern Poland, had lost 550,000 men, 70 percent of its total strength, compared with 200,000 casualties on the Russian side. Nor could Hitler mend this gaping hole torn into the eastern front, because the D-Day invasion of France had given him a disaster that was just as bad in the west.

By the beginning of August the Russians were on the east bank of the Vistula river, with Warsaw just on the opposite side. Thinking that liberation was only a few days away, the Poles of Warsaw revolted. Their aim was not only to give the boot to the Nazis but also to get the flag of independent Poland aloft before the Russians imposed a puppet communist government on them. Tragically, instead of helping the Poles, Stalin halted his advance into Poland and just watched while the Germans cut the Polish resistance to bits over the next nine weeks.(14)

World War II: the Allied road to victory, 1943-45. Click on the thumbnail for a full-sized map (286 KB, opens in a separate tab). From Wikimedia Commons.

With the assault on Germany having (temporarily) run out of steam, Stalin spent the late summer and fall of 1944 stripping Hitler of his Axis partners. When he launched an attack against Romania on August 20, it only took five days for the Romanians to surrender and join the Allies, leaving twenty German divisions in the country to be quickly overwhelmed. In the first week of September Bulgaria also switched sides. At the same time a new offensive on the Baltic and Finland fronts made up the Finns' minds for them; they accepted Stalin's terms (the loss of Petsamo, Finland's only Arctic port; the 1940 frontier in the south; and a heavy reparations bill) and left the war.(15) So did Army Group North; in October it was forced into Latvia's Kurland peninsula, and confined there until the war ended.

In October 1944, Red Army units crossed the prewar German frontier and entered East Prussia. This was an area that had not been threatened since the battle of Tannenberg, thirty years earlier. Russian soldiers were astonished at the relative luxury of German communities; the hardships caused by war and communism meant that no part of the USSR looked that good. Some figured that the Germans were well off because they had plundered the rest of Europe, and that gave them the excuse they needed to start looting. One of the reasons why the Russian advance on the central front paused was because members of the Red Army were getting their revenge on Nazi Germany, with an orgy of plunder, arson, rape and murder. On the other end of the central front, the Red Army entered Silesia in January 1945, and the same tragedy happened there. Eight and a half million surviving Germans fled East Prussia and Silesia, clogging the roads and railroads going to other parts of Germany.

The loss of Romania and Bulgaria convinced even Hitler that it would be necessary to evacuate the rest of the Balkans. As the Germans withdrew to a new defensive line in Hungary (which held until February 1945), communist guerrilla leaders Josip Broz Tito and Enver Hoxha seized control of Yugoslavia and Albania respectively; a British landing in Greece completed the liberation of that country. In response to the loss of his allies, Hitler reversed his anti-Slavic prejudice and organized an anticommunist "Russian Liberation Army," composed of 1 million ex-POWs and led by one, General Andrei A. Vlasov. But this move came too late to be convincing, and too late to do much good; at the end of the war Vlasov's Russians were opposing Americans in Czechoslovakia, rather than trying to halt the Soviet drive from the east.

In February 1945 came a second conference of the "Big Three" Allied leaders, held at Yalta in the Crimea. At the time of the meeting Soviet troops were only 30 miles from Berlin; that plus the massive casualties suffered by the USSR gave Stalin the same negotiating advantage he had enjoyed at Tehran. Stalin agreed to support the embryonic United Nations and to declare war on Japan 90 days after the fighting ended in Europe.(16) In return for these he was given sizeable territorial concessions, permission to continue Soviet occupation of eastern Europe (though he did promise free elections there), and a role in the occupation of Germany; nobody in the West at that time expected either the second or third of these concessions to become permanent. To put it in a nutshell, what was proposed at Tehran was elaborated and confirmed at Yalta.

Once Germany's river barriers were crossed, the end of the Third Reich came quickly, especially in the west, where Germans surrendered in large numbers to American, British, Canadian and French forces, rather than risk falling into Soviet hands. The Russians crossed the Vistula River in January; three months later they crossed the Oder and entered Berlin. Hitler committed suicide a day before the Russians reached the bunker in which he was hiding, and one week later Germany surrendered.

News of the surrender reached Moscow on the morning of May 9, and thousands of people took to the streets, many of them still in pajamas, to celebrate in the way Russians do best--by drinking. They drank so hard that on May 10--probably the only time it happened in Russian history--Moscow actually ran out of vodka. The war was at last ended.

Aftermath

Russia was generously compensated for its role in defeating Germany and Japan; before long many would say too generously. In Europe Stalin kept everything he got from his pre-1941 honeymoon with the Nazis, except for the district of Bialystok, which he gave back to Poland. He also took half of East Prussia and the Ukrainian-inhabited eastern tip of Czechoslovakia; the latter gave the USSR a common border with Hungary. To make the new frontiers stable he ordered ethnic deportations on a massive scale, clearing the Soviet Union of Poles, and Poland & Czechoslovakia of Germans. In the Far East Soviet involvement was brief and unnecessary (Japan surrendered just five days after Russia invaded Manchuria), but since nobody at the time knew that would be the case, the USSR also gained much in that region: the Tuva district of Mongolia, the Kurile Islands, south Sakhalin Island and Port Arthur. The USSR also temporarily occupied parts of Germany, Austria, Korea and China (Manchuria). In all of these except Austria the Red Army stayed long enough to remove the few remaining factories and made sure that those who ruled after they left would be communists.

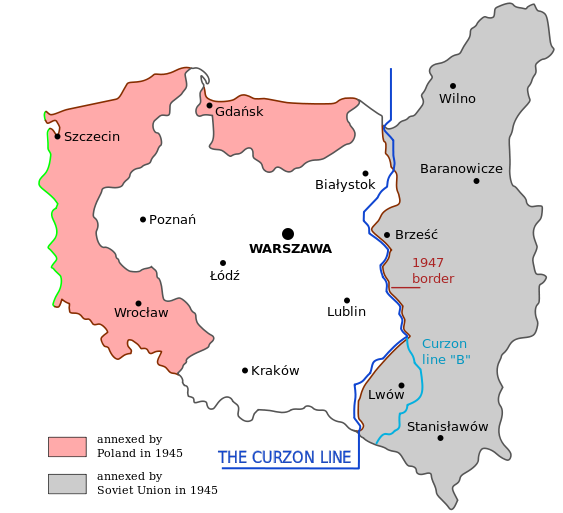

Poland in the twentieth century. At the end of World War I, the Polish state was given the white territory west of the "Curzon Line," shown here in blue. By winning the Russo-Polish War of 1920, the Poles added the grey area to their country, too. After World War II, the Soviets took back the grey area, and gave Poland the pink areas (Pomerania, Silesia, Gdansk and half of East Prussia), which used to belong to Germany. You could say that Poland was picked up, carried more than a hundred miles west, and dropped down again; e.g., Warsaw used to be in western Poland, but it's in eastern Poland now. The white and the pink areas still belong to Poland today.

Although these gains added 265,850 square miles and 23,477,000 people to the USSR, the Soviet Union actually controlled less European territory than the old Russian Empire did, thanks to the independence of Poland and Finland. When Averell Harriman, then the American ambassador in Berlin, asked Stalin if he was happy to have his soldiers in Berlin, the Soviet dictator answered wistfully, "Yes, but those of Alexander I were also in Paris."

This is the end of Part II. Click here to go to Part III.

FOOTNOTES

8. Gulag is a Russian-language acronym, meaning "Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps and Labor Settlements." The Gulag system of labor camps worked much like the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, in that they served the double function of producing forced labor for the state, and getting rid of those individuals deemed unfit to live in normal society. Conditions in the camps were so awful that the Gulag is now considered one of the most horrid examples in recent history of man's inhumanity to man, but not much was known about the camps until a former inmate, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, published The Gulag Archipelago in 1973. He called the system an "archipelago" because the camps were scattered all across the Soviet Union, like a cluster of islands.

The largest camps were in the parts of Siberia that the government wished to develop, which also sharply limited the ability of prisoners to escape. Those who broke out and managed to get past the guards, dogs and barbed wire found themselves in a frozen wilderness, probably hundreds of miles from the nearest town or city. The most hideous Gulag stories tell of escaping prisoners that invited another inmate, preferably someone young and trusting, to come with them. Then when they got away and their food ran out, the inmate that had been brought along would be killed and eaten. Russians grimly referred to the victim in this case as a korova, or cow, because the escapees took him with the intention of slaughtering him later, like a real cow. And even those who survived long enough to make it to civilization were still in the Soviet Union; getting out of the USSR was another adventure altogether.

9. One Finnish soldier, Simo Häyhä (1905-2002), has gone down in history as the deadliest sniper of all time. If you put his name into a search engine, chances are you will get a bunch of pages that honorably call him "badass." In the 1920s Häyhä did his mandatory one year of service in the army, and after that he lived the dull life of a farmer, with some hunting in his spare time. When the USSR invaded Finland, he was called back to active duty, and sent to Kollaa, a forest north of Lake Ladoga. This area saw the toughest fighting of the Winter War, with around 8,000 Russians killed and wounded -- and almost one tenth of those casualties were Häyhä's. Most of the time he would hide in the trees and snowbanks with his rifle and a couple cans of food, and he singlehandedly made 505 confirmed kills this way. Add to that another 200 kills after the Finnish army gave him a submachine gun, and his final credited kill-score was 705. Even more amazing, the rifle he used the most was a bolt-action M/28-30, a vintage World War I weapon, meaning he usually could only get one shot at a target, and he refused to use a telescopic sight, because the glint of sunlight on the sight could have given away his location.

Naturally, the Russians were terrified when they learned that one man they could not see was picking off so many of them. They called him the "White Death," and sent out first a task force, and then a team of counter-snipers, just to take out Häyhä; in both cases the White Death killed them all. Finally on March 6, 1940, some Russian made a lucky shot and hit Häyhä in the face, but even then he did not die. Instead he went into a coma, and was rescued by his buddies; he woke up a week later, on the same day that Finland surrendered, and though he had lost a cheek to the shot, he lived to a ripe old age.

Simo Häyhä, the "White Death."

10. Because of the beating Finland took from the USSR in 1940, it didn't take much to persuade the Finns to re-enter the war on Germany's side. Today's Finns refer to their involvement on the Russian front in World War II as the "Continuation War," because they see it as the rematch after the Winter War. When Operation Barbarossa began, the Finns waited until the Russians launched a major air raid against Finland on June 25, 1941; then Finland declared that the Soviet Union had broken the previous year's treaty, and declared war. However, they were only interested in getting back the land they had lost in the Winter War. By the end of 1941 they had recovered the land, and also captured the territory between Lakes Ladoga and Onega, giving them the whole southern half of Karelia. Along this line they dug in, hoping to hold their gains until the Germans won the big battles. Two and a half years of inconclusive trench warfare followed, until the Russians launched their 1944 counter-offensive. Throughout the whole war the Finns were reluctant members of the Axis; they allowed food to get into Leningrad from their direction while the city was under siege, and they refused to participate in the Holocaust.

Finnish reluctance may help explain how one Finnish soldier, Lauri Törni (1919-65), became a hero in three countries: Finland, Germany and the United States. A veteran of both the Winter War and the Continuation War, he hated the Soviets so badly that he didn't want to stop fighting when Finland did, so he defected to Germany; his experience allowed him to join the SS. However, Germany also surrendered less than a year later, and Törni ended up in a British prisoner of war camp. Escaping from that, he returned to Finland, but the Finnish government now considered him a traitor; it first threw him in jail, then changed its mind and pardoned him in 1948. After that Törni moved to the United States, changed his name to Larry Thorne, tried working as a carpenter, got bored, and took advantage of a law that allowed foreigners to become US citizens, if they served in the US Army for five years. Thorne started out in the US Army as a private; he couldn't transfer his officer's rank from previous service in other armies, but he was such a talented soldier that he rose quickly through the ranks, eventually becoming a captain. Finally he got his wish to fight the communists some more, by taking part in the Vietnam War. Here he served so bravely that he was award a bronze star and five purple hearts, before getting killed in a helicopter crash in Laos. As a result, he is probably the only former Nazi buried in Arlington National Cemetery. For more about Larry Thorne's amazing story, click here and here.

11. The original name for Stalingrad was Tsaritsyn. During the Russian Civil War, Stalin led the Red Army force that defended Tsaritsyn from Admiral Kolchak, so he renamed the city after himself in 1929. Just the name was enough to give Hitler an obsession for capturing this place.

12. An effort was made by the Luftwaffe (German air force) to airlift supplies into Stalingrad, because they had successfully supplied the German force in Demyansk the previous winter. It failed for two reasons. First, the Sixth Army was more than twice as large as the Demyansk garrison, so the logistics of keeping the troops fed and clothed were much more difficult. Second, the airlift itself was badly organized. In one case, thousands of right shoes were sent without matching left shoes. Another time the soldiers received four tons of spices, as if somebody thought they were chefs or sixteenth-century explorers! And when the soldiers opened one shipment, they were stunned to discover millions of condoms. Third, the Russians stationed anti-aircraft guns close enough to shoot down many of the planes when they tried to leave again.

13. Stalin was really worried that the British would begin the liberation of the Continent by landing in the Balkans rather than France, a move which would have kept the Red Army out of most of the future Warsaw Pact countries. By getting an Allied promise to launch D-Day in the west instead, he gained a major diplomatic victory, with results that would not become clear until years after the war ended.

14. Stalin could never get along with the Polish government in exile, which he scornfully called "the London Poles." In 1941 he released most of the Polish soldiers he had captured two years earlier, but not the 15,000 officers who led them; when the Polish government demanded to know where they were, all he said was, "Maybe they have fled to Manchuria." The truth was that he had executed them in 1940, adding them to his long list of atrocities. In April 1943 the Germans discovered the mass grave of these officers in the Katyn forest, near Smolensk; the USSR accused the London Poles of believing slander, broke diplomatic relations with them, and set up a communist government, "the Lublin Poles," to oppose the pre-1939 regime. When the Red Army finally liberated Warsaw and western Poland in January 1945, there were only communists left to rule the area. A similar denial of help to non-communist Slovaks late in 1944 gave the USSR uncontested control of Slovakia.

15. A number of Germans were caught in Finland when the Finns surrendered, and at first they were allowed to leave the country peacefully; by September 15 all Germans in southern Finland had departed. However, the German navy mined the Gulf of Finland, and tried unsuccessfully to take Suursaari Island. Because of this incident, and because the Russians insisted that German soldiers be disarmed and handed over to them, fighting broke out between the Germans and Finns in the third week of September. German forces in the northern third of Finland occupied the territory instead of leaving, causing a conflict known as the Lapland War. The Finnish general Hjalmar Siilasvuo drove most of the Germans out in October and November, but before withdrawing to Norway, the German commander, Lothar Rendulic, retaliated by destroying more than one third of the homes in Lapland, burning down Rovaniemi, the provincial capital, and leaving landmines to kill and maim civilians. A Russian army got involved by driving west from Murmansk, occupying the Norwegian province of Finnmark in the winter of 1944-45. The last Germans, holed up in the northwest corner of Finland, were finally expelled on April 25, 1945, less than two weeks before World War II ended in Europe.

16. At that time, before the first test of the atomic bomb, it was feared that the war in the Pacific might continue until 1947.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Russia

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|