| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

A Concise History of China

Chapter 6: THE NATIONALIST YEARS

1911 to 1949

This chapter covers the following topics:

| The Warlord Period | |

| Chiang Kai-shek vs. the Communists | |

| The Long March | |

| The Second Sino-Japanese War Begins | |

| Stalemate & Stagnation | |

| Ichigo | |

| The Final Showdown | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

The Warlord Period

The revolution that toppled the Manchu regime came so suddenly that even Dr. Sun Yat-sen was taken by surprise. On October 10, 1911, there was an accidental explosion in Wuzhang, the capital of Hubei province. The investigating authorities found lists of the revolutionaries in the city; to avoid arrest, the revolutionaries launched an uprising that soon won the support of the local soldiers. From Wuzhang the revolution spread like wildfire. Sun Yat-sen was in Denver, Colorado when he heard the news; when he got back to China, two months later, he that found three fourths of China Proper had gone over to him. On January 1, 1912, Sun's followers proclaimed the Chinese Republic, with its capital at Nanjing and Sun as its first president.

While the revolution overran central and southern China almost bloodlessly, most of the army stayed loyal, and it was not willing to give up the north so easily. Sun chose to negotiate with the commanding general, Yuan Shikai; he offered Yuan the presidency if he would bring the army around to support the revolution. Yuan agreed. The last emperor, a six-year-old boy named Pu Yi, was quietly removed from office, though he was allowed to stay in the northern half of the Forbidden City and the Summer Palace until 1924. Sun Yat-sen stepped down, after being president for only two months, and the seat of government moved to Yuan's headquarters in Beijing.(1)

Once in power, Yuan Shikai attempted to turn the clock back on the revolution. To start with, he charged Sun Yat-sen and his idealistic followers, the Guomindang (Nationalist Party, formerly spelled Kuomintang), with sedition and expelled them from the new parliament. Then he delayed the writing of a constitution until articles were added that gave him dictatorial powers. Those cabinet members who were not scoundrels like himself were either bribed into silence or assassinated outright. In 1916 he crowned himself emperor of a new dynasty. Riots broke out all over the country in protest, some of them started with Japanese help (we'll see why shortly). A few months later Yuan died without naming a successor, and the country went to pieces.

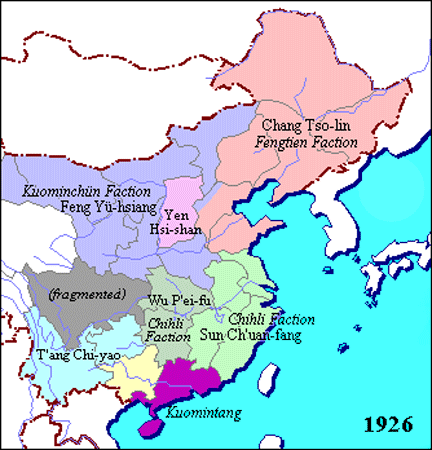

The period of Chinese history from 1916 to 1928 is commonly called the "Warlord Period." Today's Chinese also call this the time of "The Three Mores," because as they put it, there were "More officers than soldiers, more soldiers than guns, and more bandits than people." Nearly every province was ruled by an independent warlord (Sichuan had seven!), and they fought one another to gain control over all of China. The warlords varied greatly in character, from ex-generals to the 13th Dalai Lama of Tibet to a German baron in Outer Mongolia, but most of them had no political philosophy except "I'm the best!"

While a national government continued to exist in Beijing, it could not represent the nation or exert any control beyond the North China Plain. What it did do was act as a front for the warlord currently ruling Beijing. Whoever controlled Beijing and the national government enjoyed diplomatic recognition from foreigners, and got the customs duties and taxes (read: money) collected in Chinese ports by them, so the city of Beijing was the most fought-over part of the country.

In the north, after the previously mentioned baron, a communist revolution occurred in Mongolia, and Russia's Bolsheviks used this region's long distance from everybody to detach both Mongolia and the Tuva district from China, by establishing Soviet satellite governments in them. While Moscow recognized these as independent states right away, China did not recognize the loss of Mongolia until 1945; that's why pre-World War II maps are fuzzy about whether Mongolia belonged to China or not.

Across China, few serious attempts were made at tax, land, or economic reform; instead most warlords ruthlessly collected taxes, often many years in advance, and forced many farmers to divert land from food to more profitable cash crops, such as opium. This drove millions of already impoverished peasants to starvation; many joined the local armies so they could at least have a full stomach at the expense of the other peasants. The devastation caused by the fighting, coupled with the irregular requisitions made by the ill-disciplined armed forces, made every village dread the arrival of a military unit, no matter which side it was on.

During these years World War I took place in the West; both Japan and China declared themselves on the side of the Allied powers. The German port of Kiaochow on the Shandong peninsula was taken by the Japanese in 1914; from China's point of view that meant replacing one ruthless colonial power with another. Soon after that the Japanese issued twenty-one demands upon the Chinese government; these demands would have made China a puppet state of Japan if Yuan Shikai had complied. Yuan balked on some of them, though, and the Japanese sent aid to two of his opponents.

After World War I ended Japan, Britain and France were allowed to keep their Chinese ports and all of their economic interests in the country. The Chinese were on the same side but they got nothing whatsoever. For many Chinese this treatment at the hands of their allies was the last straw. On May 4, 1919, student demonstrations against the Versailles treaty and foreign imperialism took place all over the country. The May 4th movement, as this event is now called, is important to modern Chinese history for the following reasons:

1. It persuaded the Allies to re-negotiate the future of their Chinese assets. For example, Japan gave back the port of Kiaochow in 1922, and Britain returned Weihaiwei in 1930.

2. It gave new life to the Guomindang--now confined to Guangdong province--as the only Chinese political faction with a serious plan for the future.

3. It encouraged those students who had studied Marxism to form a Chinese Communist Party, which had its first meeting in Shanghai in 1921.

The Guomindang's response to these events was to establish diplomatic relations with the only European nation that did not sign the Versailles treaty: Russia. The Soviet government was now finished with the bloody civil war that put it in power, so it was more than willing to help any friend it could find. Soviet advisors, led by Mikhail Borodin, came and helped the Guomindang modernize its armed forces. Borodin's first act was to establish a modern military school, the famous Whampoa Academy, on the island of Huang Pu near Canton. Then he arranged for an alliance between the Guomindang and the fledgling Chinese Communist Party (CCP); the communists joined the Guomindang and many of them--including future communist leaders Zhu De, Lin Biao, and Zhou Enlai--rose to the top of the party's ranks, giving the Nationalist Party a leftist character from 1923 to 1927.

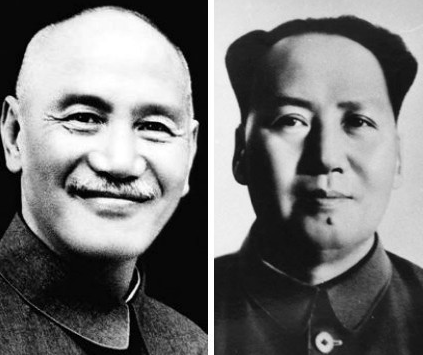

Another member of the CCP was not yet important, but would be soon. This was Mao Zedong(2) (1893-1976), a well-to-do peasant from Hunan province, a traditional center of Chinese revolutionary activity. He got started on this path in 1918 when he went to Peking University, where he worked as library assistant under Li Dazhao, the founder of an important Marxist study group and one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party. Mao began to emerge as a distinctive leader with a new program for revolution when he wrote a report for the Communist party in 1927 about the peasant movement in Hunan. In that document Mao expressed his belief that the revolution must base itself on peasant uprisings, a view that was condemned by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist party, which closely adhered to the Russian policy of basing the revolution on the urban proletariat.

Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, and a Moscow-educated officer named Chiang Kai-shek(3) (1887-1975) took his place. A rigidly formal man with gray eyes--unusual for any Asian--he had led a regiment financed by a Japanese-based secret society that joined forces with Sun in the 1911 revolution, and kept in touch when Yuan Shikai's crackdown forced him to flee to Japan. When the Warlord Period began, Chiang returned to Shanghai, where he made a fortune speculating on the Shanghai stock exchange. He also had connections with Shanghai's most notorious group of criminals, the Green Gang, which controlled much of the city's trade in opium, gambling, prostitution, and protection rackets. His wealth and influence was increased further in 1927, when he married a sister of the wealthiest banker in China, T. V. Soong; another sister was the widow of Sun Yat-sen. He became Sun's logical successor by serving as the first director of the Whampoa Academy.

These were not the credentials of a committed socialist, and despite the time he spent in the USSR, Chiang had a pathological hatred of communism. Furthermore, he had too many emotional ties to the United States, which did not recognize the Soviet Union until 1933.(4) But he knew he looked best when he cultivated the image of a revolutionary nationalist, and he was greatly admired by Borodin, so for the time being he accepted the help of the Russians and the communists. The most cultured of the communists, Zhou Enlai, became his personal assistant during this time. Meanwhile, Chiang also accepted aid from those inclined to be anti-communist, like the Japanese and the Shanghai business community. To the warlords he promised rank or money if they would join his side.

A year after taking over Chiang felt ready to begin the march northward, to reunite China under Guomindang rule. Helped along the way by the chronic disunity of the warlords, peasant and worker uprisings, the communists, and a friendly warlord in Shanxi province, Chiang's expedition was a complete success. By the end of 1926 he had reached the Yangtze River in Hubei; in 1927 he captured Shanghai; when he took Beijing in 1928, Zhang Xueliang, the warlord of Manchuria, surrendered without a fight. The entire eastern half of the country was now under Chiang's rule.(5)

Chiang Kai-shek vs. the Communists

Meanwhile, the left wing of the Guomindang grew exponentially; by 1927 the ranks of the communists had swelled to 70,000. After the 1927 battle for Shanghai Chiang decided it was time to break with the Reds while he was still stronger. In Shanghai it was easy; the communists wore red scarves to identify themselves, and in the summer weather the heat made the dye run from the scarves and stain their necks. When that happened the communists discarded their red clothing, but they couldn't hide the tell-tale stain; all Chiang's soldiers had to do was shoot any "redneck" they found. The Green Gang helped Chiang's army, and together they massacred about 5,000 leftists.

Those Reds who survived went underground or fled to rural areas. In response Chiang brutally suppressed the communists and their sympathizers wherever he could find them, killing 100,000 of them in Wuhan alone by the summer of 1928. Borodin managed to escape to Moscow, where he fell victim to Stalin's purges in the 1930s. When the Chinese Communist Party held its Sixth Congress in a Moscow suburb (1928), it had fewer than 10,000 members left.

Chiang's purge had eliminated communism in the cities, but peasant disaffection, caused by his failure to carry out land reform, provided new possibilities in the countryside.(6) Mao Zedong was the first to realize this, and his base of operations in Jiangxi province became the birthplace for a new form of communism. At this time most Chinese communists (and their Soviet advisors) still believed that a communist revolution should follow the traditional Marxist formula, starting with workers' uprisings in the cities. Mao disagreed, arguing that a non-industrialized country like China has no urban proletariat worth speaking of; one should instead look to the peasants for a real source of revolution. The years between 1927 and 1934 are marked by the success of Mao's strategy and the failure of the previous party leaders; consequently Mao's group became the largest base of communist activity in China.

Mao had his first test of leadership in his native Hunan in 1927, in a movement called the Autumn Harvest Uprising. It was a disaster. The peasants responded with apathy to Mao's calls for insurrection; those who did were poorly equipped and badly trained. Mao narrowly escaped with his life after being captured by Nationalist troops. He was dismissed from the Politburo of the Communist Party for this, but unaware of this action, he set up a new base in Jinggangshan, a notorious bandit lair in Jiangxi province. There he was joined in 1928 by 600 survivors. Among them was Zhu De, a professional officer from Sichuan who would later be hailed as the creator of the Red Army; Chen Yi, the deputy of Zhou Enlai (who remained in Shanghai until 1933); and a brilliant twenty-one-year-old soldier named Lin Biao, who would eventually become Mao's heir apparent.

While Zhu and Lin worked at turning peasants into soldiers, Mao became the political commissar of what was now called the "Jiangxi Soviet." He gave the soldiers their political training, reducing complicated patterns of thought to sets of slogans that even the illiterate could easily learn. For example, the rules of conduct were summarized in the "Three Principles": Obey orders at all times; do not take even a needle or a piece of thread from the people; turn in all confiscated land to headquarters. To deal with the superior numbers and weapons of the Guomindang, the Red Army played a cat-and-mouse game, never staying in one place for long, never attacking the enemy unless it had a clear advantage. This unconventional form of warfare that Mao and Zhu perfected has been studied and practiced by guerrillas everywhere since that time. The Red Army summarized it in this quatrain:

"When the enemy advances, we retreat.

When the enemy camps, we make trouble.

When the enemy seeks to avoid trouble, we attack.

When the enemy retreats, we pursue."

Instead of confiscating whatever they needed from the peasants, as the Guomindang and warlords did, the communists behaved as servants and liberators to the civilians they met. They repaired damages, performed public works, and never took anything from the peasants without payment. The notoriously greedy landlords, however, were fair game; wherever they went the communists executed landlords and divided their wealth between themselves and the poor. Because the peasants were encouraged to participate in these killings, they could expect no mercy from the Guomindang, and this collective guilt made them stay loyal to the Red Army after it moved elsewhere.

Chiang did not rest easy while all this was going on. In 1930 he launched what he called an "annihilation campaign," sending 100,000 troops--supplied mainly from the nearest warlords--to exterminate Mao's 30,000-man Red Army. But the rugged hills and narrow valleys of Jiangxi were perfectly suited for guerrilla tactics, allowing the communists to isolate and capture individual units of the enemy. The result was better than even Mao expected: 9,000 prisoners were captured, along with 8,000 rifles and machine guns, plus two radios that were promptly used to give the Red Army modern communications. The capture of the payroll for three Nationalist divisions was also a welcome bonus.

While Chiang was preoccupied with the communists, Japan threw a wrench into his plans. In September 1931, a covert team of Japanese soldiers planted a bomb near the Manchurian city of Mukden (modern Shenyang), which blew a 31-inch crater next to a railroad track owned by Japan. Damage was minor, and no Chinese faction was blamed for this bit of sabotage, but the Japanese army stationed in Mukden used it as an excuse to leave its barracks and occupy the whole city--to restore order, of course. Nor did the Japanese stop with that; next they called for reinforcements from Japanese-ruled Korea, which fanned out to occupy the whole northeast. This put Chiang in an impossible situation; the country was under attack, but he knew that no Chinese army could defeat the fully modern Japanese army. Therefore he chose to look the other way, hoping that Japan's ultimate goal was not the conquest of China but an invasion of the Soviet Union.(7) Zhang Xueliang, the warlord in charge of the Chinese army in Manchuria, agreed with this sentiment, and ordered his troops not to resist the Japanese advance, though it meant giving up most of the territory he had controlled.

By March 1932 the Japanese had all of Manchuria. The region became a Japanese puppet state named Manchukuo, and former emperor Pu Yi was called in from exile to rule it. Then in 1933 the five warlords of Rehe (the province between Manchuria and Beijing) and Inner Mongolia chose to submit to Japan rather than fight. To the outside world, Manchukuo was obviously an artificial political creation; there had been no call to give the Manchus their own country, nor had they demanded their emperor back. Only two nations gave Manchukuo diplomatic recognition -- Italy and El Salvador. When Japan saw it wasn't winning friends or influencing governments the right way, it became the first nation to resign from the League of Nations, showing that the organization meant to maintain world peace was toothless. However, this did not mean that anyone on China's side would fight to put the Japanese back in their place. In the early 1930s, no government was willing to say stop to Japan.

The Chinese communists declared war on Japan almost immediately, which increased their popularity among the peasants. Chiang, on the other hand, stalled for time by avoiding a direct confrontation with the new enemy. He continued to see communism as a greater evil than Japanese imperialism, and kept trying to stamp out the Red Army while the Japanese advanced to the gates of Beijing. The public was outraged, but Chiang felt that losing the northeast was worth the aid that the Japanese were still sending him to fight the communists (see the previous footnote). "The Japanese are a disease of the skin," he said later. "The Communists are a disease of the heart."

The failure of the first annihilation campaign caused Chiang to try three more, which also failed miserably. The communists repeated the tactics they had used before, relying on their superior mobility and knowledge of the terrain. They also used psychological tricks, such as wearing enemy uniforms to confuse the opposing forces and pick them off one at a time. Their greatest advantage was the support of the local peasants. One Guomindang general described the situation with these words: "Wherever we go we are in darkness; wherever the Reds go they are in light." Finally, Chiang's warlord allies were reluctant to fight on behalf of the Guomindang; they believed, with some truth, that their men were being used as cannon fodder while the Nationalist army was kept intact in the rear, the better to coerce everybody else.

For the fifth annihilation campaign, started in late 1933, Chiang's strategy was different. He brought in German advisors, and surrounded the Jiangxi Soviet with barbed wire and pillboxes, the idea being to starve the Reds into submission. This time nearly a million troops, backed by tanks, modern artillery, and aircraft, were pitted against the 180,000-strong Red Army.

The communists could expect a slow death if they stayed, but the city-bred and Comintern-educated leaders of the party refused to budge; having been forced out of Shanghai, they could not bear to give up the peasant soviet they had worked so hard to build up. Instead they tried to build fixed positions to match those arrayed against them, and told the troops: "Don't give up an inch of soviet territory."

As the siege continued through the winter, the soviet ran short on salt, cloth, kerosene, and other vital materials. A shattering military defeat in April 1934 killed 4,000 communists and wounded 20,000; desertions reduced the Red Army even more rapidly. Mao, Zhu, and Zhou Enlai proposed that the Red Army break out of the ring of steel surrounding them at several points and regroup elsewhere. Not until October did the situation become serious enough for their associates to take this idea seriously. On October 18, 1934, 85,000 troops concentrated in the southern town of Yudu, breaking out at the point where the Guomindang stranglehold was weakest. 6,000 soldiers and 20,000 civilians were left behind, many of them Mao's supporters, which reflects his poor standing in the party hierarchy at this date; most of them were executed by the Guomindang when they overran the now abandoned soviet. Mao also left three of his children behind; he never saw them again.

The Long March

This was the beginning of the Long March, a thirteen-month, 6,000-mile-long journey that became a modern legend. At this point the communists had no idea of this and no plans for where their next base would be; they just marched west, hoping to re-establish themselves either in Hunan or Sichuan. Chiang moved his army west to close both options, and at the Xiang river in southern Hunan, there was a one-week battle that cost the communists 30,000 casualties. Once the Red Army was across the river, Chiang threw more troops and fortifications in the way, forcing it to wander around for weeks in the mountains of Guizhou province, unable to break through enemy lines. Once again the Guomindang generals thought they had the Reds bottled up, but low cloud cover hid most of the communists from the nationalist planes, allowing them to elude their pursuers again. Then the Red Army captured a major town, Zunyi, and there it camped for a month while it planned its future.

This meeting was the turning point for the Chinese Communist Party. After an exhaustive review of what had happened so far, it was concluded that the orthodox approach of the party leaders, most of whom were trained by the USSR or the Comintern, was impractical and a complete failure. Mao was elected as the party's new chairman and Zhu De became its military commander, with Zhou Enlai--now and henceforth a firm ally of the chairman he had disagreed with previously--as Mao's chief political officer.

By the time the Red Army started moving again, it had shed its printing presses and other heavy equipment so it could travel light, carrying only food, ammunition, and weapons. Now the plan was to pass through Yunnan, turn north to cross the Yangtze River and join up in Sichuan with other communists dislodged from their soviets in Hunan, Hubei and Anhui. Almost every day there were skirmishes with pursuing Guomindang forces. Ten years later, a Red Army general, Peng Dehuai, claimed that there were so many battles, he could not accurately remember anything else that happened. "Now when I look back, it seems to be one enormous battle going on all the time."

High in the mountains of Sichuan and close to Tibet, the Red Army began facing natural hazards that were as dangerous as the enemy. About 200 miles north of the Yangtze River, the Tatu River cuts through steep gorges; at some point it had to be crossed, but along a stretch of 100 miles, there were only two bridges and one ferry. Two Guomindang regiments guarded each bridge and a fifth watched over the ferry.

Zhu De made a feint to distract the garrison at the southern bridge, while he sent a regiment ahead to capture the ferry. Crossing fifty miles of rugged country in twenty-four hours, they surprised the local commander and his officers, capturing them while they played mahjongg at a relative's feast. A native of the region, the Sichuanese commander had not believed that strangers could cover the distance in such a short time.

Contrary to Chiang's orders, there was a ferryboat docked on the south bank of the river when the communists arrived. A volunteer squad of sixteen Long Marchers took it across the river under fire, securing a beachhead that was used to get nearly a division to the other side. But now it was spring, meaning that the river was flooded and more treacherous than usual to travel on, and Chiang had reinforcements closing in. Under these conditions it would take weeks to get everyone across, so the Red Army commanders decided to capture the northern bridge.

In two days, a regiment made a forced march of 100 miles, resting only for ten minutes every two hours and with soldiers falling asleep as they marched. They found the bridge intact. Famed throughout the province, it had been built at great expense in 1701 by the emperor Kang Xi, and the Sichuanese warlord in the local town of Luding could not bring himself to destroy it. Instead he removed the wooden planks that made up the floor of the bridge, leaving just thirteen huge iron chains swaying over the tumbling river; it was thought that nobody in his right mind would try to use the bridge by climbing on the chains. But a unit of twenty-two soldiers did lead the way on the bridge chains; three were shot into the waters below, while the rest rushed the enemy on the other side, securing the bridgehead for those few critical moments needed to capture the bridge and get the rest of the Red Army across.

The next obstacle was seven mountain ranges, the most formidable being the Jiajin Shan (Great Snow Mountains). Crossing it took the marchers to an altitude of 16,500 feet; they suffered terribly from lack of oxygen and from the cold, since their clothing was quite inadequate. One marcher recalled, "All along the route we kept reaching down to pull men to their feet only to find they were already dead."

Waiting on the other side of the mountains was another Red Army force slightly larger than Mao's, led by a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party named Zhang Guotao (1897-1979). Zhang had been the commander of the Red Army base closest to Shanghai, the Eyuwan Soviet (on the Anhui-Hubei border), until the Guomindang dislodged him in 1932; since that time he had been wandering around in northern Sichuan. It turned out to be a chilly reunion. Mao and Zhang never got along; they immediately argued over who should lead the Communist Party, and where the Long Marchers should go from there. Mao argued for either Shaanxi or Ningxia, two rich provinces on the edge of the north China plain. Zhang preferred a base in Xinjiang, which was closer to the Soviet Union and thus relatively easy to supply. After a month of meetings failed to resolve the differences, the two rivals went their separate ways, Mao going north, Zhang moving farther west into the mountains between Sichuan and Tibet.(8)

The last obstacle in the Red Army's path was later remembered as the worst. This was the Grasslands, a trackless wilderness stretching for hundreds of miles along the Sichuan-Gansu border. No trees grew here, only clumps of grass hiding treacherous bogs. Sometimes the soldiers had to sleep kneeling back to back because there was no place to lie down. No landmarks guided the way, and the mists that blanketed the area often caused units to get lost and perish. Because it was impossible to carry stretchers, the sick usually had to be abandoned. And plenty of men were ill; the temperature dropped below fifty degrees F. every night, even in August, and there was no rice to eat, only a local strain of wheat which most of the men could not digest. On the fringes of the swamp Tibetan tribesmen--who hated all Chinese, whether the army was red or white--ambushed isolated units at every opportunity. As many as one third of the force died in the week it took to cross this terrible region.

Finally in October 1935, 20,000 survivors straggled into northern Shaanxi. Probably only 8,000 of them had been on the Long March since it began; the rest were recruited on the way. Here at last, at the town of Yan'an, Mao found a suitable spot for a new base that was safely out of Chiang's reach; during the next two years he was joined there by communists fleeing from other parts of the country. Yan'an remained the communist headquarters for the next twelve years.

Despite his losses, Mao had created a legend about an unbeatable army (fueled later by communist propaganda) which did not loot the poor, and whose officers and men, sharing the same uniforms and rations and dangers, preached an end to the injustices of high taxation and rent. The peasants would remember this during and after the next critical test, this time against the Japanese.(9)

The Second Sino-Japanese War Begins

Chiang was still as determined as ever to crush the communists, so he announced yet another extermination campaign. He ordered the Manchurian army under Zhang Xueliang and his Northwestern army under Yang Hucheng, both based in Shaanxi, to attack the communists. But these soldiers, particularly the homeless Manchurians, wanted to fight the Japanese instead; they sympathized with the communist slogan "Chinese don't fight Chinese." In December 1936, the generalissimo flew to Xian, the capital of Shaanxi, to take charge of the campaign. Instead he was arrested and held hostage by Zhang, who demanded that Chiang call off the civil war and form a united national army to stop the Japanese. Zhou Enlai, Chiang's former associate, led the communist team that came to negotiate the terms of the alliance. Some of Zhou's colleagues wanted to put Chiang on trial, but the Soviet Union pressured them to come to terms with their sworn enemy; Joseph Stalin felt that Chiang was the only leader strong enough to unite China against Japan, an enemy the Russians also feared. Faced with an apparent choice of cooperation or death, Chiang finally saw reason and agreed to an uneasy truce with the CCP. His reward was not only his release but also a considerable amount of Soviet military aid, including 1,000 planes and 2,000 pilots. In addition, the CCP agreed to adhere to Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People, abandoned the confiscation of landlords' property for the time being, and made the Red Army a component of the Nationalist army under the central government.(10)

As you will see in the next paragraph, the "Xian Incident" came just in time before the next Japanese move, but Zhang Xueliang gained nothing by forcing Chiang to turn his attention from the communists to the Japanese. As soon as the Guomindang leaders were away from troops loyal to Zhang, Chiang had Zhang put under house arrest. After that, Zhang was confined wherever the Nationalist capital happened to be. In 1949 he was taken with the Guomindang to Taiwan, and remained there under house arrest until after Chiang's death in 1975.

On July 7, 1937, the Japanese began their invasion of the rest of China. As with Manchuria, the invasion began with an act of violence, this time a skirmish on a bridge near Beijing. From there the Japanese army overran Beijing and Tianjin quickly. Then Shanghai was bombed savagely as a second Japanese army landed on the central coast and advanced up the Yangtze valley. Taking Shanghai put Nanjing within striking distance, and when Chiang Kai-shek tried to defend his capital, the attackers captured it anyway, and they tried to make an example of Nanjing to break Nationalist morale. During the next two months, the Imperial Army indulged in an orgy of destruction in which 20,000 women were raped and between 200,000 and 400,000 civilians were killed (the notorious "Rape of Nanking" incident). But as Nazi Germany found out when it bombed Britain in 1940, atrocities against civilians tend to have the opposite effect; they increase the determination of the survivors to resist until the end.

While Japan's naval and air superiority was unquestioned, Japan never committed its full strength to conquering China. The Japanese Army was always concerned about the prospect of fighting the Soviet Union, while the Japanese Navy was equally watchful over the United States. But though they pulled their punches, the Japanese won victory after victory against the Chinese. By the end of 1937, the Guomindang government had moved its capital to the central Yangtze metropolis of Wuhan.(11) By mid-1938, the Japanese controlled all major northern Chinese cities, and the railway lines in-between. In October they took Canton and Wuhan, so the Guomindang government moved again, this time to Chongqing (Chungking) in Sichuan, farther up the Yangtze and relatively inaccessible behind a protective mountain screen (the site of the present-day Three Gorges Dam). The Japanese did not pursue Chiang farther upstream than Wuhan, but by occupying the ports on China's southern coast, along with the island of Hainan, cut off most of his links to the outside world. The only ways left to get military and civilian supplies to Chiang was by roads from French Indochina and British-ruled Burma.

At the end of the first phase of the war (1937-8), the Nationalists had lost the best of their armies, air force and arsenals, most of China's industries and railways, its major tax resources, and all their ports had been taken or isolated. The Japanese advance ground to a halt, at the cost of hundreds of thousands of peasants, who died from either floods or famine in the war zone. What China still had was a vast though backward territory in the interior, and unlimited manpower reserves. So long as China continued to resist, Japan's control over the conquered east, as well as its war effort elsewhere, would be difficult to sustain.

Stalemate & Stagnation

Between 1939 and 1943 the battle lines changed very little and all engagements were on a limited scale. Japan sent repeated air raids against Chongqing, killing thousands of civilians in an effort to bomb Free China into submission. After 1940 the Japanese put the China campaign on the back burner while they expanded their "Co-Prosperity Sphere" in other directions, occupying the Pacific and Southeast Asian colonies of the Western powers.

Chiang Kai-shek's longterm strategy was to trade space for time. He made little effort to recapture lost territory; the most significant victory his troops won was in March 1938, when they inflicted 16,000 Japanese casualties in the battle of Taierzhuang (in Shandong province). He did not even bother to declare war on Japan until 1941. He was biding his time because he expected the United States to enter the war on his side, and then together they would win. Until then, he would fight the Japanese only when he could not retreat, keeping his government and army intact so he could take control of the whole country upon the war's end.

The result of Chiang's waiting was an erosion of morale among the Guomindang. Deprived of the revenues obtained by trade and customs, the Nationalists financed the budget and lined their own pockets by printing paper money without gold or other reserves to back it up. This caused massive inflation, raising prices 250-fold between 1942 and 1944, and the wages of most workers failed to keep up. Local governors also introduced new taxes, limited only by their imagination; among these were the "contribute-straw-sandals-to-recruits" tax, a "comfort-recruits'-families" tax, and a "train-antiaircraft-cadres" tax. The Guomindang government-in-exile became so corrupt and unpopular that the local residents of Sichuan called them "downriver bandits." For this reason, the Guomindang made no effort to mobilize the peasants as the communists were doing.

The war had the opposite effect on the CCP. Not believing in enforced idleness, the communists infiltrated the Japanese-controlled areas of north China and began to organize resistance. The railway system, secured by blockhouses every few miles, was an ideal target for guerrillas on the move. Soon the Japanese only had firm control over the parts of the countryside that they happened to have troops in. In response the Imperial Army launched what it called the Three Alls campaign: Kill all, loot all, and burn all. When that began the Red Army deliberately avoided pitched battles, restricting itself to harassing the enemy. "The people are the sea," declared Zhu De's deputy, "while the guerrillas are the fish swimming in it." Meanwhile, Mao Zedong worked at winning local support by reducing rents and taxes and improving the standard of living in the areas they controlled. The result of all these actions was that Yan'an became a magnet for idealistic young people from all over the country. This swelled the ranks of the Communist Party from 40,000 in 1937 to 400,000 by 1940.

In 1939, the United States, Great Britain and France joined the Soviet Union in providing aid to the Guomindang. More aid--both in money and arms--came in 1940, when Japan made a formal alliance with Nazi Germany and Chiang warned he would have to make some sort of accommodation with the Japanese if he could not beat them on the battlefield. He really had no intention of following through with this threat, but the possibility of a Chinese collapse was taken seriously when Wang Jingwei, Chiang's chief deputy and political rival, defected to the Japanese and was installed as the head of a puppet government in Nanjing. Elsewhere, warlords and generals teamed up with the Japanese, in a few cases fighting with them against the communists.

The beginning of World War II in Europe all but ended European contributions to the Chinese war effort, especially after Germany invaded the USSR. One by one the Japanese cut off the supply lines to Free China from the outside; by mid-1941 supplies to Chongqing were forced to come in either by an air route from Hong Kong, or via the 715-mile long Burma Road, which ran from Kunming (the capital of Yunnan province) to Lashio, the nearest city in Burma connected by road and railway(12). The USA supplied fighter planes and pilots--the famous Flying Tigers Squadron--in early 1941. In December of 1941 the USA and Britain entered the war, thanks to Japanese attacks on their territories. One of Japan's new targets was Hong Kong; it was attacked on December 8, and taken on December 25.

For what the Americans called the CBI (China-Burma-India) theater, they sent General Joseph Stilwell, to command the troops there and serve as Chiang's chief of staff. Stilwell, like Chiang, was tough as nails (he soon was nicknamed "Vinegar Joe"), and disagreements caused the two leaders to develop a strong dislike for each other; e.g., Stilwell gave Chiang the nickname of "Peanut." At one of their early meetings, Chiang stunned Stilwell by telling him that Chinese divisions should not be deployed even in defensive positions unless they outnumbered the Japanese by at least five to one; in fact, the generalissimo continued, Chinese forces should never be massed, since that would be an invitation for the Japanese air force to destroy them wholesale. "What a directive," Stilwell wrote in his diary. "What a mess."

The Chinese did serve with distinction alongside American and British forces in Burma, but Chiang was probably right. Most of the Nationalist army was in terrible shape, and the best soldiers were kept in the north to contain the communists. Most of the troops were conscripts who were in theory chosen by ballot, but the process was warped so that the rich were spared and the ranks were filled with miserable, illiterate peasants, who were treated more like coolies than regular soldiers. Many conscripts had to walk hundreds of miles to reach their units, and as many as 44% of them deserted or died of disease/malnutrition on the way. During the war the Guomindang mobilized some 14 million troops, and 3 million of them became combat casualties, many of them dying of infection from relatively minor wounds that went untreated. Most of the remaining 10+ million are simply unaccounted for; they probably either deserted or died of starvation (food was so rare that officers often stole it to sell on the black market). Morale was so bad that there were reports of soldiers on leave being chained together to keep them from deserting.

It was a very different story in the communist zone. When the United States sent its first official representatives to Yan'an in July 1944, they found such a contrast that one delegate said, "We have come into a different country, and are meeting a different people." The communist leaders had survived over a decade of civil war and had developed a unity, camaraderie, and a powerful sense of mission that would see them through hard times. They claimed control over 310,000 square miles land and 95,000,000 people, about a fourth of China's population. They enjoyed widespread support and the troops were loyal, well-disciplined, and highly motivated. Finally, the Red Army did not abuse the rights of civilians.

Many Americans questioned whether the Guomindang was fit to govern a liberated China, but their warnings were drowned out by Patrick Hurley, President Roosevelt's flamboyant ambassador to China, whom Mao regarded as little more than a mouthpiece for the generalissimo. When Hurley's clumsy efforts to set up a democratic coalition government that included both Nationalists and communists broke down, he urged Washington to give its full support to Chiang alone. In all fairness, it would have been difficult for the US to do anything but that, since Chiang had already been recognized as the rightful leader of China. The Soviet Union also regarded Chiang as the legitimate head of state, despite Stalin's strong backing of the CCP. Furthermore, Stalin did not like the way the Chinese communists were deviating from the orthodox Marxist line. Soviet wags called the Chinese style of communism "two peasants wearing the same pair of pants," and on a stopover in Moscow, Stalin told Hurley that Mao's supporters were really "radish communists--red on the outside, white inside."

Ichigo

The Japanese launched their last offensive in the spring of 1944, long after the Axis had been forced to retreat everywhere else. The objective was to starve Chongqing into submission, either by capturing the Allied airfields at the western (Indian) end of the Hump, or by taking the Chinese airfields used by the United states on the eastern end. The first attack, an invasion of India from Burma, was turned back after 4 months (March-July 1944) and the Allied liberation of Burma began. The Chinese part of the campaign, known as Ichigo (Operation One), was more effective in that it showed how weak, inefficient and poorly led the Nationalist armies were after nearly seven years of war. During April and May the Japanese cleared the Peiping-Hankow railway and conquered Henan province. They traveled at night to avoid attacks from the Flying Tigers, which constantly bombed their lines of march. Every time a Chinese force opposed the Japanese, it was overcome. Some of the Chinese soldiers were even attacked by their own countrymen, who were enraged by the excesses of other soldiers; starving peasants disarmed retreating Nationalist troops, shot them, and welcomed the Japanese.

June saw the beginning of Ichigo's second phase, a pincer movement of two armies from Wuhan and Canton to take Guilin and open a land route between Central China and Southeast Asia. Changsha, the capital of Hunan province, had been successfully defended against Japanese attacks in 1939, 1941 and 1943; now it was quickly taken. By November all of Guangxi and eastern Hunan had been overrun, and the Japanese were approaching Guiyang, the capital of Guizhou province. At this point they had also captured all but three of the American airfields in south China. If Guiyang fell, they would be in an easy position to go after both Kunming and Chongqing. This was the high watermark of Japan's war in China.

Guomindang incompetence led to a falling out between Chiang and the Americans. General Stilwell insisted that he be made supreme commander of the China-Burma-India Theater; Chiang balked at the idea of Stilwell outranking him, and the dispute between them got so heated that Washington had to replace Stilwell with another general to save the alliance. In October 1944 the United States began its campaign to liberate the Philippines, and there had been plans to land American troops on the south China coast when the Philippines were secured. But now that the Americans were disillusioned with Chiang's government, they dropped the idea of a Chinese campaign, and the B-29 bombers stationed in China were transferred to the Marianas Islands.

In December the Japanese force moving on Guiyang was turned back, and the first four months of 1945 saw limited offensives to consolidate the gains of 1944. They finally stopped when the threat of war with the USSR prompted them to withdraw several divisions to defend Manchukuo and the homeland. Between May and July the Nationalists took advantage of this, recovering Guangxi and western Guangdong, as well as the port city of Wenzhou, but most Chinese territory captured by Japan remained in Japanese hands until the end of the war.

Chiang knew that taking control of and rebuilding China would be a monumental task. Aware of his army's own weaknesses, he was still hoping an American invasion force would drive out the Japanese for him; that looked likely after the war ended in Europe. Indeed, the Americans drew up a plan to liberate Canton and Hong Kong in August, called Operation Carbonado. But the dropping on Japan of the first atomic bombs--a weapon neither the Chinese nor the Soviets knew the Americans had--meant that Operation Carbonado would not be needed, and American forces would not have to come to China at all. Instead the newcomers were the Soviets, who had promised to declare war on Japan no later than 90 days after Germany surrendered. On August 9, one and a half million men, 3,704 tanks, and 3,721 aircraft from the USSR invaded Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, crossing the frontiers at twelve points. It was a lightning advance that resulted in a decisive victory; eight days after the invasion began the Japanese commander of the largest force in the northeast, the Kwantung Army, received news of Japan's surrender to the Allies. Negotiations began with the Russians the next day (August 18) and a surrender document was signed on the 19th, giving up all of Manchuria and northern Korea to the Soviets.(13) For the Soviet Union it was a last-minute triumph that contributed nothing to the Allied victory over Japan, but spread communist control over a vast new stretch of territory.

The United States rushed 53,000 marines to the cities of Beijing, Tianjin and Qingdao, just in case the Russians got too enthusiastic about their advance, but Stalin promised to return all Chinese territory he had captured. In fact, Chiang asked the USSR to stay in the northeast until he could move his own troops there. Now that the US no longer needed the enormous arsenal it had stockpiled in China, it was turned over to the Nationalists, and American pilots flew Guomindang representatives to take the surrender of the Japanese, even in sectors claimed by the CCP; Chiang also ordered those Japanese soldiers not yet disarmed to resist the Red Army.(14)

The Final Showdown

Because the war had lasted for so long in China, the amount of death and destruction was appalling--though China came out on the winning side, it wasn't much better off than the countries that lost. Throughout the war, the Allies had put on a show of making it look like China's contribution to the war effort was almost as important as the American and British contributions, hiding the real weakness of the Guomindang and its troops. Then with the founding of the United Nations at the end of the war, the United States made China look like a major power again, by insisting that the Nationalist government hold one of the five permanent UN Security Council seats.

Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-shek had his own plan for the postwar years--he would destroy communism in China. On the other side, Zhu De ordered his men to move into Japanese-held territory and confiscate Japanese arms, in clear defiance of Chiang's order for the Red Army to stand where they were. Red Army General Lin Biao became commander of the communist forces in Manchuria, now known as the Northeast Democratic Allied Army, which included former "puppet" troops of Manchukuo as well as new volunteers. The next four years can be divided into three phases: (1.) from August 1945 to the end of 1946, the Nationalists and Communists built up their forces, raced to grab as much land as possible, and fought limited engagements while negotiating at the same time; (2.) during 1947 and the first half of 1948, big battles were fought, with the Nationalists winning at first until the strategic balance tipped in favor of the Communists; (3.) the rest of 1948 and 1949, when the Communists won the smashing victories that led to their final triumph.

Unwilling to see a new war break out in the heart of its ally so soon after the previous war ended, the United States sought for a peaceful solution. In December 1945 President Truman defined American policy toward China: the United States regarded the Nationalist regime as the legal government of China but since it was a one-party system, it was necessary that full opportunity be given to other groups to participate in a representative government. To that end, Truman urged an end to the fighting. General George C. Marshall, US Army chief of staff during the war and future author of the Marshall Plan that would restore western Europe, was sent to do whatever he could to keep the Nationalist-communist alliance from coming undone. Leading a negotiating committee of three that included Zhou Enlai and Nationalist general Chang Chichun, Marshall tried everything he could to bring the two sides back together, including a summit meeting between Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong. But both sides were convinced that they could win on the battlefield what they could not win on the negotiating table--namely dominance over the other side. In January 1947 Marshall left China, confessing his mission a failure and denouncing the intransigents on both sides. "The greatest obstacle to peace," he reported, "has been the complete, almost overwhelming suspicion with which the CCP and the Guomindang regard each other." The last negotiations ended in March, and the die was cast for war.

On paper, it looked like just about every advantage was with the Nationalists. They had more than three million men in their army, many of them trained by Britain and the United States. They had 1,000 American-supplied planes, while the Communist air force was practically nonexistent. Most of the cities and major sources of revenue were under their control, and Chiang enjoyed the security of being regarded as a near-equal partner by Britain, the United States, and even the Soviet Union. On the Communist side the Red Army had under 1 million men, of whom only about half were even armed, and Mao's name was still not well known outside of China. For this reason, Stalin hinted that Mao should form another coalition with Chiang, with the CCP as subordinate partners. The USSR also did not actively help the Communists while it had troops in Manchuria, choosing instead to dismantle the local factories and ship them back to Russia, along with hundreds of thousands of Japanese prisoners of war.

Chiang was so certain of his strength and the need to attack now that nothing could make him do more than pay lip service to the truces hammered out by the Americans. In June 1946 he started to move in force against the Communists, and for a while his armored divisions were successful everywhere against the lightly armed Reds. Many of the early battles were fought over Manchuria, a vital iron and coal-rich region that holds much of China's railroads and industry. The Soviets did not withdraw until June 1946, allowing Lin Biao's Communists to seize control of more than half of the Manchurian countryside in the meantime. Once the Nationalists arrived, however, the advantage went to them, and after a month of bloody fighting, Lin was forced to retreat. By the middle of 1947, the Guomindang controlled virtually every major city, and the main transportation routes. Even Yan'an had fallen into the hands of the Guomindang.

But Chiang's chosen tools were unreliable ones. His personal integrity was beyond question, but his Nationalist associates had lived for eight years in Sichuan on a combination of inflation, graft and American aid. Instead of changing their habits, they descended on the rest of the country like robber barons. Loyalty to Chiang was more important than competence, and indeed it can be said that they were loyal precisely because they were so incompetent. But they did not let their loyalty get in the way of enriching themselves; corruption at every level of the administration made sure that the generalissimo's orders did not get obeyed. He also lost the support of the middle class, which was expecting democratic and economic reforms, only to see them postponed indefinitely.

On the other side the Communists used the same strategy which had worked against the Japanese: avoid indefensible positions and do not fight battles when the enemy has the advantage. No longer restricted by the alliance of World War II, they also renewed their land reform program, confiscating and redistributing the property of the landlords, often killing the landlords in the process. The party tried to control the process in order not to alienate those peasants who had done well in recent years, but soon the land reform took on a momentum of its own, and rural China went through a reign of terror. Despite excesses the CCP emerged more popular than ever; morale had been raised to a fever pitch and, for those who had gained from the land distribution, there was no turning back.

Economic problems added to Chiang's military dilemma. The Nationalists had been unable to rebuild the economy after 1945, and the answer to uncontrolled spending was to simply print more money; about 65% of the government's budget was financed by the printing press and only 10% came from taxes. This caused inflation to soar out of control. By mid-1948, the U.S. dollar came to be worth 93,000 Chinese dollars on the black market, and one pound of rice cost almost 250,000 Chinese dollars. In August the government introduced a new dollar bill, the Gold Yuan, to replace the old notes at a rate of 3 million to one, showing how worthless the money had become. Speculation, hoarding, black market operations and excessive regulations also hindered commerce, despite draconian attempts to stop them. Each night, people starved to death in the streets, their bodies collected by garbage trucks in the morning. Serious riots broke out, and thousands of workers went on strike in Shanghai. In the Communist-controlled areas, by contrast, there was little starvation, because the Communists lived without cash, using what was in effect a barter system. Nor was hoarding of food permitted; rations were the same for all ranks.

Chiang's army--poorly equipped, miserably paid, and suffering low morale--now began to disintegrate. Support for Chiang had to be enforced on the point of a bayonet, and hungry Nationalist troops began defecting to the other side, happy to exchange their rifles for a square meal. At the beginning of 1947, an entire Nationalist division went over to the "People's Liberation Army." Ignoring warnings from the US that his troops were dangerously overextended, Chiang refused to give ground.

In September 1947, Lin Biao resumed the offensive in Manchuria and Shandong. Soon his men had shut down the railway system in Manchuria, isolating 250,000 of Chiang's best troops in the cities of Harbin, Changchun (the former Manchukuo capital), and Mukden. And every major city on the north China plain was under siege as well.

By the end of 1947 the Nationalist forces were in full retreat. Defections increased; indeed, of the Nationalists who fell into Communist hands, three quarters simply surrendered. In the autumn of 1948 the Nationalist presence in Manchuria collapsed(15); by now the relative strengths of the two sides had been reversed.

The last year of the war saw the communists capture city after city, frequently facing only token resistance. The most important battle was fought for sixty-five days on the banks of the Huai River, just outside of Nanjing. Half a million troops were committed on each side; the Nationalists had the advantage in armor and air power, but the outcome was decided when the Communists cut communications and picked off Chiang's divisions one by one. Whole Nationalist units switched sides with all their military equipment. When the battle ended on January 10, 1949, the ancient port of Nanjing, Suzhou, was captured, and the Nationalist capital lay exposed.

At the end of January the "People's Liberation Army" entered Beijing without meeting any resistance. Chiang Kai-shek temporarily resigned, and the Nanjing government sued for peace. But negotiations proved hopeless. Mao Zedong wanted nothing less than a complete surrender of the other side, and the Nationalists were not prepared to do that while they still had a large army and three quarters of the country. In April Mao ordered his troops to cross the Yangtze and go for a final victory.

On April 25 Chiang abandoned Nanjing for the second time, retreating to Canton.(16) In May the Communists captured Wuhan, Shanghai, and Xian. The rest of the year saw the Communists overrun the provinces remaining to the Nationalists in the south and the western provinces controlled by the Ma Family Clique, a family of Moslem warlords (Gansu, Ningxia, Qinghai and Xinjiang). The last Guomindang-held city on the mainland, Chengdu, fell in December; when that happened, Chiang Kai-shek and nearly two million of his followers fled to the island of Taiwan, taking with them most of the government's gold reserves and the Nationalist Air Force and Navy. Another group of 12,000 Nationalist soldiers fled across the border into Burma; they staged raids on Yunnan province and gave the Burmese government trouble for many years.

Chiang stayed on Taiwan for the rest of his life, despite vows to return to the mainland some day. Aside from Taiwan there was only Tibet, a minor warlord in the remote mountains of western Sichuan, some Moslems in the west who refused to submit to communist rule, and offshore islands like Hainan; most of those were subjugated by May 1950.

Right-wing Americans, influenced by the demagoguery of Senator Joseph McCarthy, charged that liberals and "fellow travelers" (those who supported social aims similar to the communists') lost China. U.S. American military aid to China during World War II totaled $845 million; from 1945 to 1949 it came to slightly more than $2 billion. As was the case in Vietnam a generation later, it is extremely doubtful whether pouring additional American military aid into China could have changed the final outcome of the civil war. The bulk of the Nationalist forces had lost the will to fight. Large quantities of American arms sent to Chiang's army were turned over to the communists by apathetic Nationalist leaders.

On October 1, 1949, Mao appeared at the entrance to the Forbidden City, the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tiananmen), and proclaimed the People's Republic of China. "Ours will no longer be a nation subject to insult and humiliation," he declared. "We have stood up." But he also had a word of warning of what was to come. "The victory of the Chinese people's democratic revolution, viewed in retrospect, will seem only like a brief prologue to a long drama. A drama begins with a prologue, but the prologue is not the climax."

Even Mao probably could not predict the major events his actions would cause during the rest of the twentieth century: involvement in the Korean and Vietnam wars; the lunacy of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution; and the ups and downs of China's relations with the rest of the world. The peasant boy from Hunan had come a long way, but as far as he was concerned, the journey was not yet over. "Our past work", he declared, "is only the first step in a long march."

This is the End of Chapter 6.

FOOTNOTES

1. Beijing means "northern capital," and until the late twentieth century it was usually spelled "Peking." However, during the years when Chiang Kai-shek ruled from Nanjing or Chongqing, it was known instead as Peiping, meaning "northern peace." The "southern capital" was Nanjing, of course.

2. Mao Tse-tung in pre-1979 texts.

3. Chiang Kai-shek is also a south Chinese name; in Pinyin it is spelled Jiang Jieshi.

4. Chiang was a Methodist convert, and his in-laws, the Soong family, lived in the USA. After Chiang's death, Madame Chiang (1897-2003) returned to New York City.

5. The western warlords, except for the Dalai Lama, swore loyalty to the Guomindang, and thus were allowed to keep their positions, some of them as late as 1949. The governor of Xinjiang got Soviet help to put down a Uygur rebellion in 1931, and for the next eleven years, the Soviet consul in Xinjiang had so much power that the province was Chinese in name only; for all intents and purposes, Xinjiang was a satellite of the USSR, like Mongolia and Tannu Tuva.

6. Even in peacetime the peasants suffered under high rents and interest rates that approached 80 percent. And when a particularly bad famine struck (see Chapter 1, footnote #2), it went almost unreported in the world press.

7. At the time this was not a totally unreasonable assumption. The militant leaders of Japan hated communism as much as Chiang did, and not until 1940 did they decide that the USSR was too strong for them; that was when they decided to attack Pearl Harbor instead.

8. A year later Zhang Guotao tried to establish his base on the far northwestern frontier. His force was ambushed by the Moslem warlords of the northwest, in cooperation with the Nationalists; they were so badly mauled that only 2,000 of them made it to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang. Now discredited as a general, Zhang was flown by a rescue plane to Mao's new headquarters in Shaanxi. In 1938 he defected to the Guomindang, but was never given an important position under them, so he moved to Hong Kong in 1949, and to Canada in 1968. One year before his death, he converted to Christianity.

9. Chiang Kai-shek failed to destroy the communists, but he did strengthen his control over the southwest, by removing the warlords in the areas the Guomindang troops marched through.

10. The Red Army became the Eighth Route Army at this point, and later the 18th Group Army.

11. Before the mid-twentieth century, Wuhan was three cities--Hankou, Hanyang, and Wuzhang--which grew together following industrialization.

12. When the Japanese conquered Burma in May 1942, they also cut off the Burma road; they finished extending their control over the south China coast when they captured Hong Kong on December 25, 1941. Now the only supply line left to the Guomindang was a dangerous air route from northeast India (Assam) to Kunming, over a part of the Himalayas nicknamed "the Hump."

13. Pu Yi, the last emperor of China and Japan's puppet ruler over Manchukuo, was captured by the Soviets and locked up in a Communist Chinese prison camp until 1959. After his release, he went back to Beijing and became a gardener on the grounds of the Forbidden City, the same place where he had once been hailed as the "Son of Heaven." He died there in 1967.

14. Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands were returned to China when the war ended, and France handed over its enclave at Guangzhouwan in the same year (1945). However, the Soviets got the Japanese naval base at Port Arthur (modern Luda), on the southern tip of Manchuria, and they did not give it to the Chinese until 1958.

Hong Kong almost went the way of Guangzhouwan; it wasn't returned to China because of some quick thinking on the part of a British civil servant, Franklin Charles Gimson. Gimson arrived in Hong Kong as its new colonial secretary on December 7, 1941, the day before the Japanese attacked and seized the colony. Like most British civilians in Hong Kong, Gimson was taken to the Stanley Internment Camp, where he spent most of the next four years. After Hong Kong's governor was removed from the colony, Gimson found himself the highest-ranking prisoner in the camp, so he became the spokesman and unofficial leader of the internees. During those years they received no news on how the war was going, so they had to guess that the Allies had won on August 15, 1945, when the Japanese suddenly lifted all restrictions and regulations on them. The terms of Japan's surrender called for Japanese troops to maintain order in the areas they occupied until Allied forces could take their place. To keep Hong Kong from falling into the wrong hands during this precarious time, Gimson first declared himself lieutenant governor, a title he had just made up, then acting governor. He managed to hold on for two weeks, until British warships arrived at the end of August. What Gimson did not know was that the United States was planning to give Hong Kong to Chiang Kai-Shek. Why the Americans thought of doing such a thing without Britain's permission is unclear; perhaps US President Harry Truman felt the British were willing to do it, now that Winston Churchill was no longer prime minister. If it had not been for Gimson's action, Hong Kong would have quickly passed first under Nationalist, then Communist rule, and it would have missed out on half a century of stupendous prosperity.

15. It required a lengthy siege (June-October 1948) to capture Changchun. At least 160,000 civilians are believed to have perished. A Communist lieutenant colonel, Zhang Zhenglu, wrote a book about the siege, White Snow, Red Blood, and compared it to the dropping of the A-bomb on Hiroshima: "The casualties were about the same. Hiroshima took nine seconds; Changchun took five months." From Andrew Jacobs, "China Is Wordless on Traumas of Communists' Rise", The New York Times, October 2, 2009.

16. In 1948 Chiang Kai-shek's son, the future Taiwanese president Chiang Ching-kuo, bought a villa in Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang Province, and Chiang Kai-shek briefly stayed there as well. Naturally the Communists seized the villa when they took over the city, and for the rest of the twentieth century it served as a government employee residence. Then the Communists discovered who had lived in the villa previously, and declared it a cultural relic in 2004. However, it was a money-losing property for its owners, so in 2015 it was converted into a McDonald's! Because zoning laws allow historic properties to be turned into businesses as long as open flames are not used, the villa became a McCafe, not a full-fledged restaurant, and there are pictures on the walls telling about the villa's most famous owner. Still, many Chinese see it as an example of Western commercialism running over Chinese culture, and you have to admit it shows present-day China doesn't follow communist doctrine like it used to. In fact, the Forbidden City in Beijing hosted a Starbucks from 2000 to 2007.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A Concise History of China

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|