| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 5: Uncle Sam's Backyard, Part V

1889 to 1959

This chapter is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Big Picture | |

| Cuba Libre! | |

| Costa Rica: King Banana | |

| The War of a Thousand Days | |

| The First US Occupation | |

| Mt. Pelée Kills St. Pierre | |

| The Panama Canal | |

| Peru: The Aristocratic Republic | |

| Venezuela: The Tyrant of the Andes | |

| Colombia: The Conservative Republic | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 1: Conservatives vs. Liberals |

Part II

| Uruguay's Welfare State | |

| The United States Occupation of Haiti | |

| Argentina: The Radicals In the Saddle | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 2: Moderates vs. Radicals | |

| Independent Cuba: The Early Years | |

| Guatemala: A Cultured Brute and a Napoleon | |

| Brazil: The Old Republic | |

| Honduras: La Republica de los Bananas | |

| Chile: Parliamentary and Presidential Republics |

Part III

| Ecuador: The Leftover Country | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 3: Coming Full Circle | |

| The Dominican Dictator | |

| The Chaco War | |

| El Salvador: The Coffee Republic | |

| Uruguay: The Terra Era | |

| The Somoza Dynasty, Act One | |

| Panama: The Bisected Protectorate |

Part IV

| The Infamous Decade | |

| Getúlio Vargas and the Estado Nôvo | |

| Colombia: "The Revolution On the March" | |

| The Battle of the River Plate | |

| Bolivia: Contending Ideologies | |

| Cuba: Batista's First Reign | |

| Venezuela In Transition | |

| The Rise of Juan Perón | |

| Haiti: Elections and Coups | |

| Peru: APRA vs. the Army | |

| Paraguay: The Rise of the Colorados | |

| Costa Rica: The Unarmed Democracy | |

| "There's No Place Like Uruguay" | |

| The Bolivian National Revolution |

Part V

Cuba: The Auténticos and the Second Batistato

The constitution Cuba adopted in 1940 did not allow the president to have two consecutive terms, so Fulgencio Batista stepped down when his term ended in 1944. However, the man he picked to succeed him, Carlos Saladrigas Zayas, was defeated in a fair election by Ramón Grau, who now became president for the second time (1944-48). Deciding not to live in Cuba under another Grau administration, Batista moved to the United States; when asked about it, all he said was, "I just felt safer there." There were unsubstantiated rumors that he had taken part of the national treasury with him, to make Grau's job more difficult. Most of the next eight years were spent either at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, or at a home in Daytona Beach, Florida. In 1948 he tried running for president again, but lost to Carlos Prío Socarrás, so Prío was president for the next four years (1948-52).

Grau made a deal with the labor unions to continue Batista's pro-labor policies. His administration oversaw programs to build public works and schools, increased social security benefits, and encouraged economic development and agricultural production. Unfortunately, prosperity also silenced calls for economic diversification, and brought corruption. Under Batista the corruption was mainly financial (bribes, embezzlement, etc.), but under Grau, political nepotism and favoritism, coupled with urban violence, grew at an alarming rate. In Havana the Mafia became visible enough to give the city a reputation as a base for organized crime.

Prío came from Grau's political party, Partido Auténtico (Authentic Cuban Revolutionary Party). He was so polite that people called him El presidente cordial ("The Cordial President"). He launched more public works projects and founded the National Bank and Tribunal of Accounts, but his government's reputation was ruined by increasing corruption and gangsterism, made worse because the postwar bust in sugar prices meant the country could no longer afford either the corruption or the government's expensive programs. Still, with hindsight, Prío does not look as bad as either Batista or the Castro family. Later he told Arthur Schlesinger: "They say that I was a terrible president of Cuba. That may be true. But I was the best president Cuba ever had."(86)

At first, the most vocal opponent of the Auténticos was Eduardo Chibás, a charismatic populist and the founder of Partido Ortodoxo (Orthodox Party), a party that emphasized clean government. He denounced both Grau and Prío for letting corruption run wild, and many expected him to run for president in 1952. But Chibás thought that either a coup or fraud would keep him from winning, so after making a speech on the radio, he committed suicide. The 1952 campaign became a three-way race, with Roberto Agramonte of the Orthodox Party leading in the polls, followed by Carlos Hevia of the Auténticos, while Fulgencio Batista, who came back for another try at the presidency, ran a distant third.

Outgoing president Prío heard rumors that Batista was planning a military coup, but because he saw nothing in the constitution authorizing him to act, he did not do so. Unfortunately the rumors were true. On March 10, 1952, three months before election day, Batista and his collaborators seized military and police commands, radio and TV stations. He cancelled the elections and appointed himself the "provisional president," while Prío boarded a plane and went into exile in the United States.

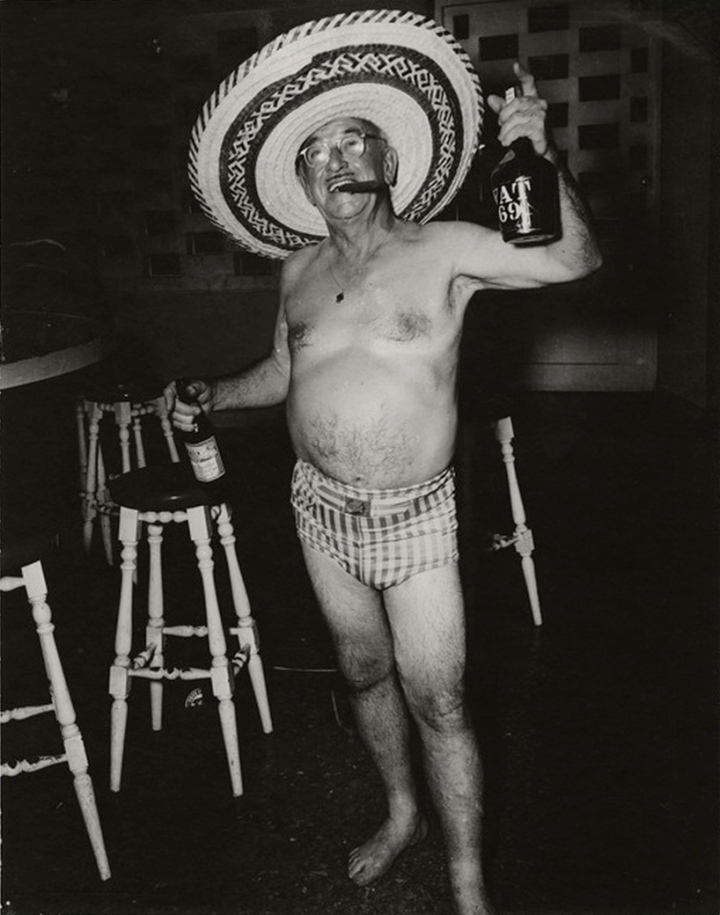

Fulgencio Batista in 1952.

Due to the corruption of the previous two administrations, the first reaction of Cubans to the coup was relief. The United States was also pleased, especially US businesses, because after Batista took over, there were no more strikes and the country was more stable. But soon everybody realized that the second Batista presidency would be different from the first; he suspended the 1940 constitution and attempted to rule by decree, and politically he shifted to the right; whereas he used to be a populist, now he became an elitist. He appears to have suffered from an inferiority complex because of his lowly birth; Cuba's upper class had never accepted him, and he wanted to join their social circles. He also worked to increase his personal fortune; instead of fighting organized crime, he made deals with it to earn a profit.

Under US pressure, Batista held elections in 1954. The CIA predicted that Batista would do anything to make sure he won the election, and he did. By using fraud and intimidation, he got most of the other parties to boycott the elections; his main opponent, former President Grau, was the last to drop out, so Batista was re-elected.

For Americans in the 1950s, Havana was the "Latin Las Vegas," a vacation hotspot where every business was dedicated to people-pleasing. This included illegal businesses as well as legal; gambling, prostitutes and drugs were all readily available. In fact, marijuana and cocaine were so common that a 1950 magazine article declared, "Narcotics are hardly more difficult to obtain in Cuba than a shot of rum. And only slightly more expensive."

Despite corruption, crime, and the lack of political freedom, Cuba prospered greatly in the 1950s. Although a third of the population still lived in poverty (mainly in the countryside), wages in the cities rose almost to the levels in developed countries. Moreover, Cuba ranked fourth among all Latin American countries when it came to education (the population was 80 percent literate at this point), and it was one of the most urbanized Latin American countries, with 56 percent of the population living in towns and cities. Cuba also had Latin America's highest per capita consumption of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones, radios and TV sets during this period. As the Cuban author/historian Humberto Fontova put it:

"When in fact Cuba had a higher standard of living in 1958 than half of Europe, a larger middle class than Switzerland, a more highly unionized work force than the U.S., more doctors and dentists per capita than Great Britain, more cars and televisions per capita than Canada or Germany, was inundated with immigrants.... I could go on--but will instead refer readers to my book for these statistics and the corresponding documentation."(87)

There were three aspects to the mid-century prosperity that weren't so rosy. First, there was the great difference in wealth between the urban and rural populations. A lot of tourists probably didn't realize how dirt poor the Cubans were, just beyond the city limits of Havana. Second, because the United States was so close, educated Cubans couldn't help knowing about life on the US mainland; they visited the states, read American newspapers, listened to American radio, and watched American movies and television. When they looked at Cuban society, they compared it unfavorably with US society, grew dissatisfied that the Yankees were richer and freer than they were, and grew frustrated at how little their government seemed to be doing to erase those differences. Third, by now it was clear that diversification would be a good idea, but the economy was still largely dependant on one product--sugar. And the nature of sugar cane agriculture contributed to unemployment; most cane workers were only needed four months of the year, so they had a hard time making ends meet, even when they were paid well. Finally, the factors that made sugar profitable were beyond the control of anybody in Cuba, namely, sugar prices and how much the United States was willing to import. Because the sugar industry decided whether each year would be a feast year or a famine year, it proved to be the weakness of both the economy and the Batista regime.

Puerto Rico: "Candy-Coated Colonialism?"

Up until the end of the nineteenth century, Cuba and Puerto Rico had almost identical histories. José Martí was aware of it; he declared that in the war of independence against Spain, the two islands would stand shoulder to shoulder as "two wings of the same dove." Maybe there weren't any revolutionaries on Puerto Rico when the Americans arrived, but the island had some a generation earlier, so who could say it would not produce revolutionaries again some day? What divided Cuba and Puerto Rico was the decision by the US government to keep Puerto Rico and let Cuba go; since the Spanish-American War, the "two wings" have followed different courses.

|

|

It took a couple years for Washington to decide what to do with Puerto Rico, after Spain surrendered; the US Congress did not make up its mind before the war, the way it had with Cuba. In the meantime, a military government was set up for Puerto Rico. It had to deal with disaster when two hurricanes struck the island in August 1899, killing 3,400 people, leaving thousands more homeless, and destroying most of the sugar and coffee plantations. After recovery from those storms, the plantations grew less coffee, and more sugar and tobacco, because there was more demand on the US mainland for the latter two products. The coffee, by contrast, had been exported to Europe, but now that market was no longer accessible.

The Congressional decision came in the form of the 1900 Foraker Act, which made Puerto Rico the first unincorporated territory of the US and established its government. This government had a governor and an 11-member executive council appointed by the president of the United States, a House of Representatives with 35 elected members, a Supreme Court and a US District Court, and a non-voting Resident Commissioner in Congress. The first civilian governor of the island was Charles H. Allen. Both Spanish and English were established as official languages.

The first decade of American rule also saw the formation of the first Puerto Rican political parties. Two of them were organized under the military government; these were the Partido Republicano (Republican Party) and the American Federal Party, led by José Celso Barbosa and Luis Muñoz Rivera, respectively. Both of those parties supported annexation by the United States, and hoped that would give native sugar growers access to the North American market (currently a US-imposed trade blockade kept them from exporting their crops). Then in 1900, right after the Foraker Act was passed, two more parties appeared. The Partido Federal (Federal Party) wanted Puerto Rico to become a state in the United States, the first party to openly call for statehood, while the Partido Obrero Socialista de Puerto Rico (Socialist Labor Party of Puerto Rico) wanted to establish some form of socialist society.

Meanwhile, Luis Muñoz Rivera had turned against the Foraker Act; he called it a disgrace because it allowed four American corporations to gain control over most of Puerto Rico's farmland. During the last thirty years of Spanish rule, Puerto Rico enjoyed considerable autonomy. Now that had been taken away; the new rulers were tactless, condescending mainlanders who had no experience in dealing with other cultures. For example, they had plans to "Americanize" Puerto Rico, starting with the local schools teaching all classes only in English; Muñoz Rivera protested that it couldn't be done, because most of the teachers only knew Spanish.(88) And when Puerto Ricans protested against an unresponsive government, the response was usually harsh. In 1904 Muñoz Rivera and José de Diego restructured the American Federal Party; they renamed it the Partido Unionista de Puerto Rico (Unionist Party of Puerto Rico), and fighting against the colonial government and the Foraker Act became their new goal. Another party, the Partido Independentista (Independence Party), was founded in 1909; as the name suggests, it wanted complete independence from the start.

However, Luis Muñoz Rivera was not a revolutionary like José Martí; he was still willing to negotiate, even when all he and the Americans could do was agree to disagree. He served in the Puerto Rican House of Representatives from 1906 to 1910, and then was Puerto Rico's non-voting observer, the Resident Commissioner in Congress, from 1911 until his death in 1916. Then in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Jones Act. Besides voiding the Foraker Act, the Jones Act made all Puerto Ricans US citizens (but they could not vote in presidential elections), and established a bicameral legislature for the island. It also made Puerto Ricans eligible for the draft; 20,000 were conscripted during World War I.

1917 also saw the United States purchase the nearby islands of St. Croix, St. Thomas and St. John from Denmark, for $25 million. Before the purchase they were called the Danish West Indies; afterwards they became the US Virgin Islands. The Americans had first proposed acquiring the Virgin Islands in the 1860s, but they didn't get around to it for fifty years. Now they were motivated to do it by the need to build more bases, to defend the Caribbean during World War I.

Since the purchase, change has come more slowly to the Virgin Islands than it did for Puerto Rico. The residents of the islands did not receive US citizenship until 1927, and they were ruled either by the US Navy or the Department of the Interior until 1936. Today it is classified as an organized but unincorporated United States territory, like Puerto Rico, Guam and the Northern Marianas. Since the current government was established in 1954, there have been five constitutional conventions; only the last one (2009) produced a constitution, and Congress rejected the proposed document.

Back on Puerto Rico, Muñoz Rivera probably would have approved of the Jones Act, had he lived to see it, but for others it left too many questions unanswered, leading to debates over the future of Puerto Rico's relationship with the US. In 1922, another pro-Independence party appeared, the Partido Nacionalista (Nationalist Party), with Pedro Albizu Campos as its most important leader. But the Nationalist platform was too radical for most Puerto Ricans, and interest in that party faded when an alternative came along.(89) The alternative was the PPD, the Partido Popular Democrático (Popular Democratic Party), founded by Luis Muñoz Marín in 1938.

Luis Muñoz Marín did better for two reasons. First, because he was the son of the widely respected Muñoz Rivera, he got attention immediately. Second, he was willing to let a plebiscite decide whether Puerto Rico should become a state or independent; the current limbo of being not-completely-American was unacceptable. In 1940 he was elected president of the Puerto Rican Senate, and he used his new position to call for such a plebiscite. However, in the late 1930s and early 40s, most PPD members favored independence; during that time, Washington did not seriously consider allowing any election that might result in a vote for independence, and laws were passed banning pro-independence activities.

We have seen already that unsatisfied reformers can turn to violence. Muñoz Marín did not resort to that because in his new position, he had plenty of other things to keep him busy. The main issue was the Great Depression. Puerto Rico suffered terribly during the 1920s and 30s, for the same reason that Cuba did--tumbling sugar prices. Under the Depression, much of the island was in a state of near-starvation. After Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, $230 million in emergency aid was sent to the island, as part of his New Deal program. Then as the 1940s began, the Great Depression ended on the mainland, but Puerto Rico's economy had not recovered yet. Working with the current governor, Rexford Tugwell, and the House of Representatives, Muñoz Marín developed a program that promoted economic recovery, agricultural reform, and industrialization. This program was called Operation Bootstrap, and it began to be implemented in 1948. The postwar years also saw thousands of Puerto Ricans move to the mainland, either because they had joined the military, or to take new jobs created by the postwar economic boom. The Puerto Rican communities now existing in states like New York and Florida got started because of that trend.

The first sign of Puerto Rico's changing status came in 1946, when US President Harry Truman appointed a native Puerto Rican, Jesús T. Piñero, as governor. However, in 1948 Piñero signed the infamous "Gag Law" (also called Law 53), which made it illegal to display the Puerto Rican Flag, sing a patriotic song, and talk or fight for the island's independence. Then later in the same year, Puerto Ricans were permitted to hold their first election for governor, and Muñoz Marín successfully campaigned for it, becoming the first elected governor on January 2, 1949.

Surprisingly, Muñoz Marín approved of the Gag Law. In the years since becoming Senate president, he had changed his mind on independence. Now he supported a status passed by Congress in 1948, called Estado Libre Associado (ELA) or Free Associated State. This was a form of autonomy similar to what he had opposed previously, except that it kept the social and economic ties that had grown over the twentieth century between Puerto Rico and the United States.

In 1950, Truman signed Public Act 600, which gave Puerto Ricans permission to write their own constitution, and declared the island's government a self-governing commonwealth in association with the United States, much like the relationship between Canada and Britain. In 1952 a referendum was held on the island about all this, and voters approved both the new status and the constitution. However, there was a nationalist minority, the followers of Pedro Albizu Campos, who still preferred independence. In the 1950s they let people know they couldn't be ignored by staging several attacks; most of them were on Puerto Rico, but there was also an unsuccessful assassination attempt on President Truman.

Today Muñoz Marín is viewed as the founder of modern Puerto Rico. He served as governor for sixteen years (1949-65), longer than anyone else, and from 1944 until 1968, his party, the PPD, won every election. He asserted that with the establishment of the ELA, the status question had been answered, but for most Puerto Ricans, nothing changed. Islanders do not have to pay income tax, their representation in Congress is still limited to a nonvoting observer, they could not vote in US presidential elections, and until the draft was abolished in 1973, they had to serve in the US armed forces. Corporations from outside are attracted here because of tax breaks and low wages (compared with the US mainland). Those advocating statehood have derided the current commonwealth as "candy-coated colonialism," but for the rest of the twentieth century, most Puerto Ricans were satisfied enough with the system to leave it the way it was.

The Ten Years of Spring

After Guatemala threw out its dictators in 1944, the army stepped aside and allowed the first free election in the country's history, to establish a civilian government. This marked the beginning of a decade of democracy, sometimes called the Ten Years of Spring (1944-54). The winner of the election and the next president was a former university professor, Juan José Arévalo Bermejo, and he served until 1951.

Colonel Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán was another veteran of the 1944 revolution and a close associate of Arévalo, so he won the next presidential election by a landslide in 1951. Árbenz continued the progressive policies of the Arévalo administration, and saw a major industrialization/diversification of the economy as the next step. But unlike his predecessors, Árbenz was determined not to use foreign capital. The only way he could do this was by increasing the money supply within Guatemala, and the way to increase the wealth of individual Guatemalans was through land reform. For that reason, in 1952 he supported a land reform bill called Decree 900, that took unused agricultural land from the large estates, gave it to landless peasants, and compensated the previous owners of the land with 25-year government bonds. The next year, he announced the same thing would be done with fallow lands owned by the United Fruit Company. Currently the UFC was only cultivating 15 percent of its land, and Árbenz offered $525,000 for the land he wanted to give to the peasants. The UFC responded that the land they were not using might be needed someday, if the existing plantations were worn out or devastated by plant diseases, and the land's real value was $16,000,000, not $525,000. In addition, the government began to tacitly support strikes by banana workers against the UFC. For the first time in history, Guatemalans were more interested in cutting back the power and privileges of US corporations, than they were in disputing Britain's continued rule over the British Honduras (modern Belize, see Chapter 4).

Looking back, one can see that Árbenz was entering dangerous ground at this point. His policies were likely to be opposed not only by conservatives and the rich, but also by very powerful US interests. One of them was John Foster Dulles, the current Secretary of Defense; he had once been on the UFC's board of trustees. And while the United States was cooperating with the revolution in Bolivia at the same time, a revolution in Guatemala was too close to both the US mainland and the Panama Canal for comfort, especially if it looked like it was becoming a Communist revolution.

Communism was a minor movement in Guatemala until 1952, when Árbenz legalized the Guatemalan Party of Labor, a Communist party. Although the party remained small, holding just 4 seats in Guatemala's 58-member Senate, Communists gained considerable influence over peasant organizations and labor unions. Whereas the Bolivian revolutionaries kept extremists from taking over their movement, Árbenz listened to leftist advisors, and gave them concessions. Now the United States grew alarmed. There was no evidence that Árbenz was dealing with the Soviet Union, but the UFC persuaded the Eisenhower administration that if he wasn't stopped, he would turn Guatemala into the first Communist country in the western hemisphere. Opponents of Árbenz, in both Guatemala and the United States, clung to small details to prove this; e.g., they accused his wife, a famous activist, of being a Communist.

The United States had imposed an arms embargo on Guatemala, so Árbenz purchased a shipment of leftover World War II-era German weapons, from Czechoslovakia. Because Czechoslovakia was a Soviet Satellite, this confirmed US suspicions. The US Central Intelligence Agency had been training and equipping Guatemalan exiles, and led by Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, they invaded Guatemala from Honduras on June 18, 1954. The CIA made radio broadcasts declaring an anti-Communist coup against Árbenz, and American pilots in CIA planes dropped propaganda leaflets and incendiary bombs on Guatemala City. The Guatemalan armed forces refused to fight the invaders, denied weapons for workers and peasants who wanted to defend the revolution, and forced Árbenz to resign and go into exile.

After the CIA coup, a military government took over, disbanded the legislature, arrested communist leaders, and ruled the country until 1966. Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas was one of the presidents during this period, serving from 1954 to 1957; his followers were described as a gang of "grafters and cutthroats." Hundreds of Guatemalans were rounded up; opponents of the government regularly turned up dead or just disappeared. The land reforms were reversed, voting was made dependent on literacy (which disenfranchised about 75% of the population), and the secret police was revived. Because the government was so repressive, and had been installed by foreign intervention, it was never popular, and at the end of the 1950s left-wing guerrilla groups began to form.

After the Mahogany Rush

In the British Honduras, mahogany production slowed during the late nineteenth-early twentieth century. One reason for this was because the trees weren't replanted after they were cut down, so loggers had to go deeper and deeper into the jungle to find them. The other reason was falling mahogany prices; unlike sugar, there were limits to the outside world's demand for the hardwood. Some entrepreneurs responded by switching to agriculture, growing first sugar, and then tropical fruits; that allowed the United Fruit Company to get a foothold in this part of Central America.

World War I was an eye-opening experience for the regiment of Creoles that Britain recruited from the British Honduras. Because they were black, they were treated worse than other Allied soldiers, and could not even fight alongside white troops on the front line. Thus, the Creoles went to war as patriotic Brits, and came back as resentful Belizeans, so the war indirectly helped Belizean nationalism get started.

With the arrival of the Great Depression in 1930, the mahogany market virtually collapsed. Employers cut the wages of mahogany workers in half, causing labor unrest; the workers joined the "Unemployed Brigade" for weekend rallies against the system, at Battlefield Park in Belize City.

Pressured by the strikes and demonstrations, the government legalized trade unions in 1941. By then the Depression was over, but World War II caused another economic crisis, because it wasn't safe to export trade goods overseas. It took the rest of the 1940s to get over that slump; after the colony recovered, the unions switched from work-related demands to political ones. In 1950 the workers founded the People's United Party (PUP), the first political party in the British Honduras. Attempts by the colonial government and rival groups to portray PUP as a communist organization only made it more popular, turning it into a full-blown nationalist movement. Following a successful general strike, universal suffrage was granted to literate adults in 1954, and when PUP was allowed to run in legislative elections, it won most of the seats. By 1961 Britain was ready to let the colony go, and began preparing it for independence in that year.

Getúlio Vargas, Back for an Encore

With Brazil a democracy again, a new constitution was drafted in 1946 that combined the best features of the 1891 constitution with the social legislation of the Vargas era. President Eurico Dutra also continued to encourage industrial development through state planning, as Vargas had done. But under Vargas, Brazil had high inflation and borrowed lots of money to pay its bills, so Dutra had to cut back on spending, and release some controls over trade to invite more foreign investments. A determined anti-communist, he made the Communist Party illegal again in 1947, now that the Cold War was underway.

For the 1950 election, Getúlio Vargas ran as the candidate of the two parties he had created in 1945. He won by a plurality, with 48.7 percent of the vote; this marked the beginning of his third term as president, and the only term that he won by election. Unfortunately, Vargas was now sixty-eight years old, and had lost his touch since the days of the Estado Nôvo. He could not cope with the country's economic problems, and nationalists were offended when he tried to get help from abroad. Nor could he get along with the legislature, which had its own agenda. There were also personal matters; he broke an arm and a leg in a fall in 1953, and suffered from loneliness, insomnia and depression. Part of the depression came from US politics; when the Eisenhower administration took over in Washington, it decided that Brazil was no longer an important ally, now that the Soviet Union had replaced Germany and Japan as the main enemy, so it promised less economic aid than the Roosevelt and Truman administrations had. Finally, because he had promised to rule democratically this time, Vargas could not silence his opponents by locking them up.

Because of corruption, always a problem where you have politicians for any length of time, the opponents had plenty to complain about. The loudest among them was Carlos Lacerda, a politician who also owned a newspaper. In 1954 there was an assassination attempt on Lacerda at his home; Lacerda only suffered a minor wound but the air force officer guarding him was killed. Vargas did not order the attack, the chief of his bodyguards did. Still, this was a huge scandal, a sign that Vargas wasn't keeping his administration clean, and there were widespread calls for him to resign. On August 24, 1954, a group of military officers delivered an ultimatum for Vargas to give up power, the way they had done in 1945. Vargas sat down and wrote a lengthy note, of which the last sentence read, "Serenely I take my first step towards eternity and leave life to enter history." Then he went from his office to his bedroom and shot himself in the chest.(90)

In the ten years between the death of Vargas and the next military coup, Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira was the only elected president that served a full term (1956-61). Because his name was so cumbersome, he is often called by his initials, "JK." Avoiding the emotional appeals of Vargas, his campaign promise was "Fifty years' progress in five," and his critics came back with "Forty years' inflation in four." What really happened was somewhere inbetween those two statements. Though the economy remained troubled during JK's term, and he was a big spender, he accomplished more than most presidents, so Brazilians remember him fondly today.

Probably the most important of JK's achievements was an 80% increase in industrial production. The growth of the automotive industry was particularly impressive. Basically, Brazil was in the horse-and-buggy era until Kubitschek took office, but by 1960 the new factories were producing 321,000 cars, trucks and busses a year. Matching automobile production was the beginning of a massive road construction project. We noted previously that there were few roads between Brazil's cities; even on the coast it was easier to travel by boat than by land, which became a dangerous undertaking during World War II, with German U-boats in the Atlantic. Now Brazil would have a great highway network, to match the Interstate highways Eisenhower was building in the US at the same time. Not only did they connect the cities, but the highways also opened up large portions of the interior to farming.

Speaking of the interior, Kubitschek created a new capital there. Up until now, Brazilians had been preoccupied with the coast, because that was where the action was. This left most of the interior untouched, and more than one visionary saw the country's future in the jungle, not on the coast. As early as 1827, José Bonifácio (see Chapter 3) presented a plan for a new city called Brasília, to be built in the middle of the country. Brazil's emperors did not act on the idea, so it appeared again in the 1891 constitution, which called for moving the capital from Rio de Janeiro at the earliest convenient date. This would not be a city that grew naturally from immigration and commerce, like Rio--the layout would be designed in advance, a fully artificial city with the federal government as its only industry, like Washington, DC. Some architects were brought in from Europe to draw plans for the city in the early twentieth century, and that was as far as the project got until JK came along and ordered construction on the city to begin. The site picked for the new city was in the Brazilian Highlands, 600 miles northwest of Rio, in the underpopulated, centrally-located state of Goiás; a new Federal District (Distrito Federal) was carved out of the Highlands for it. To make a complete break with the past, the city was given ultramodern architecture, and the streets were laid out to look like a flying bird or airplane when seen from the air; for these jobs, Lúcio Costa was the principal urban planner, Oscar Niemeyer was the principal architect of the buildings, and Roberto Burle Marx was the landscape designer. Kubitschek promised to complete Brasília before the end of his term, so on April 21, 1960, 41 months after construction started, the windswept, shadeless streets of Brasília were declared open for human traffic with much fanfare. Because of the cost and seemingly emotionless architecture, the city's existence remains controversial even today, but love it or hate it, Brasília is still the nation's modern capital.(91)

or "Don't Cry For Me Argentina"

Argentina's first elections since the 1943 coup were held in February 1946. Juan Perón ran as the presidential candidate of a brand-new political party, the Labor Party. The party platform called for the nationalization of public services (meaning railroads, hospitals, and homes for workers and the elderly), and promised to protect all the gains Perón made as Minister of Labor. Because Perón had already made a name for himself, the election attracted outside attention; the Catholic Church endorsed Perón, while the United States, noting that Perón was an Axis sympathizer during World War II, did everything it could to discredit him. When the time came to vote, gangs of pro-Perón descamisados(92) terrorized the voters, but there was general agreement that these were the cleanest elections anyone in Argentina could remember. Perón won with 54 percent of the vote; his party won almost two thirds of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies, and all but two seats in the Senate.

Juan Perón at his 1946 inauguration.

As president, Perón promoted both liberal policies and a fascist-style cult of personality. The most visible examples of this were the mass rallies he held from the balcony of the presidential palace, the Casa Rosada; often he wore a dress uniform, and the glamorous Evita stood at his side. The first years were his best; large food exports to a ravaged, postwar Europe gave Argentina a healthy trade balance, until Europe recovered under the Marshall Plan. As promised, he nationalized the banks and the railways; and in 1947 he announced a five-year plan to promote the growth of nationalized industries. His wife ran a charitable organization to help the poor, the Eva Perón Foundation, causing the public to see her as an angel of mercy; she also worked with labor and women's groups, and secured the right to vote for women in 1947. But while they had enough activity going on to suggest a revolution, the Peróns never tried to nationalize the great estates of the estancieros; they felt such a move would be too disruptive for the economy and the social structure. This showed that Peronism wasn't as ruthless a doctrine as communism, though it gave the rich a hard time politically and financially.

Peronism was brought down by the same force that discredited communism and socialism--too much regulation of the economy. Agricultural production began to fall in 1948, due to a severe drought and the farmers' reaction to unreasonably low prices the government paid for their products. Oil and coal shortages hit at the same time. Export earnings dropped 30 percent by 1949; the peso lost 70 percent of its value in two years; inflation reached 50 percent by 1951. Perón responded by decreeing an austerity package, freezing wages and prices for the next two years. Despite all this trouble, Perón won re-election in 1951.

One thing worth noting about the 1951 election is that it almost had Eva Perón as the vice presidential candidate. She was interested in the job, the working class was overwhelmingly in favor of it, and Juan Perón was impressed at her popularity, but the military and upper classes were horrified at the idea that a former actress of illegitimate birth could become president if her husband died. But after hundreds of thousands chanted her name at rally, Evita suddenly bowed out, telling the crowds that she only wanted to help her husband and serve the poor. The truth is that she probably chose not to run because she was starting to feel the effects of the cancer she had been diagnosed with in 1950. Hortensio Quijano, the vice president during the first term, ending up being the running mate again, though, ironically, he was in poor health and died before either of the Peróns did.

It has been said that behind every great man there is a great woman, and after Eva Perón died of cancer in 1952, things just weren't the same for her husband; he lost his populist touch. Rising prices and unemployment caused widespread discontent. To fix the money shortage problem, Perón let foreign corporations back into the country in 1952, and in 1954 he gave Standard Oil the right to develop oilfields in Patagonia, a move sure to offend nationalists. Opponents of the regime were imprisoned and some were tortured; censorship and a rationing of newsprint were used to stifle criticism from the press.

The Catholic Church was offended by Peronism's personality cult, and because Perón legalized divorce and secularized the schools, so Perón added the Church to his lest of enemies. Though the Church was past its prime, attacking it in Latin America was still a capital mistake; because of it, the Church rejected calls from the poor to canonize Evita.(93) Religious processions now turned into anti-Perón demonstrations, and Peronistas retaliated by burning churches in Buenos Aires.

In June 1955, Pope Pius XII excommunicated all government officials taking action against the Church, and some military aircraft tried to start a coup by bombing the presidential palace during a pro-Perón rally, killing hundreds. After several more acts of violence from both sides, Perón appeared at another rally on August 31, and called on his followers to kill five opponents for every murdered Peronista; there was also a rumor that Perón was going to pass out arms to the trade unions. Because it looked like Perón had just ordered a civil war, the armed forces began a "liberating" campaign in the provinces, later called Revolución Libertadora. In the first two weeks of September, the navy blockaded the Rio de la Plata estuary, and both the navy and air force threatened to attack Buenos Aires if Perón stayed. Recognizing that he could not win if the armed forces and the whole country beyond the capital were against him, Perón quietly slipped away to a Paraguayan gunboat in the harbor of Buenos Aires. By the rules of Latin American politics, this was giving up the fight, so the military let him go into exile, settling first in Paraguay, and later in Spain.

Perón may have been gone, and his party was banned, but his followers remained, so next the coup leaders expelled Peronistas from the military, government, courts, and universities. Military interventores were also put in charge of the trade unions. Beyond that, they weren't sure what to do. There were three possible governments for the future:

- A military dictatorship, answerable to no civilian authority.

- A partial democracy, that excluded the Peronistas from running or holding office.

- A full democracy, where everyone, including the Peronistas, could participate.

In 1958, the junta felt the country was ready for elections to set up a limited democracy. They had gone so far as to outlaw even saying Perón's name, but Perón was the main issue of the campaign anyway; everyone referred to him as El-qué-te-dije ("You Know Who"). Leading in the polls were the two Radical parties. Outgoing President Aramburu endorsed one of the Radical candidates, Ricardo Balbín, so Perón instructed his followers to vote for the other candidate, Arturo Frondizi. Though unmentionable and in exile, Perón managed to spring a "February surprise"; with the Peronist votes, Frondizi beat the junta's favorite to become president.

Unfortunately the military, Frondizi, and succeeding governments were unable to revive the declining economy or stop terrorism, which became a serious problem from the 1960s onward. The names of Perón and Evita became rallying cries for the left-wing opposition to each government. Thus, the failure to fix Argentina's troubles opened the way for Perón's return.

La Violencia

The president Colombia elected in 1946, Luis Mariano Ospina Pérez, was from the moderate wing of the Conservative Party, and he invited six Liberals to join his Cabinet and form a National Union government. The radical leader, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, was not among them; it looked like both Conservatives and moderate Liberals wanted to isolate him politically. Gaitán's exclusion, coupled with high inflation and unemployment, angered radical Liberals; they talked about a "double oligarchy"--both Liberals and Conservatives--conspiring to keep out anyone who wanted social and economic change. On the other side of the political aisle, the fiery leader of the extremist Conservatives, Laureano Eleuterio Gómez Castro, purged the National Police of its Liberal officers, and encouraged armed gangs to attack Liberals in the countryside, removing them after they had been in power for the past sixteen years. Ospina's response was to create a new police force, the policia politica, but instead of restoring order, it also sided with the Conservatives, and was nicknamed the "Creole Gestapo." Liberals--peasants, members of the middle class, and landowners--armed themselves and retaliated, and though Gaitán did not endorse violence, support for him grew dramatically.

The last time Colombians were polarized between two political parties, it caused the War of a Thousand Days, and now history repeated itself. The Church got involved on the side of the Conservatives; there were unproven accusations of several priests openly encouraging the murder of Liberal politicians during Mass. In March 1948 the Liberal Party called on every one of its members in the Conservative-run government to resign. Conservatives rejoiced; one of them wrote, "At last we are alone."

By this time, Gaitán was so popular that many felt he would win the next presidential election. Instead, on April 9, 1948, while he was walking to lunch, Gaitán was shot dead on the sidewalk. An angry mob, outraged that they had lost the only man whom they felt represented them in the government, immediately seized and killed the assassin, starting a riot called the Bogotazo; before it was over, some 2,000 people were killed, and much of downtown Bogotá was destroyed. This was the beginning of a decade of undeclared civil war called La Violencia, which spread all over the country and killed between 200,000 and 300,000.

As violence increased, the Ospina government became more repressive. Ospina banned public meetings in March 1949 and in November he ordered the army to forcibly close Congress, before it could impeach him. For the 1950 presidential election, the Liberals refused to nominate a candidate, so Laureano Gómez ran unopposed as the Conservative candidate, and had no trouble winning.

Gómez was a textbook example of a reactionary; he favored authority, hierarchy, and order, while scorning universal suffrage and majority rule. As president, he assumed dictatorial powers and offered a program that combined the values of sixteenth-century Spain with modern corporate capitalism. While import and export restrictions were removed and foreigners were encouraged to invest, pro-labor laws passed in the 1930s were canceled by executive decree, independent labor unions were dissolved, and the government dealt with strikes by making strikebreakers and blacklists legal again. When congressional elections were held in 1951, the Liberals did not participate again, resulting in an all-Conservative Congress. In the cities, civil liberties were curbed: Gómez denounced Liberals as Communists, the press was censored, courts were controlled by the president, and mobs threatened freedom of religion by attacking Protestant chapels. In the countryside, goon squads forced Liberal peasants to give up their voting cards and register as Conservatives. Communists and Liberals responded by organizing guerrilla zones, especially in the Llanos region east of the Andes; some of their commanders became legends before long.(94)

The economy improved because it was now unrestrained, but the violence, the breakdown of public order, and the repression caused Gómez to lose support anyhow. Following a heart attack in October 1951, he appointed his Minister of War, Roberto Urdaneta Arbeláez, as acting president in his place. While Gómez was recovering, Urdaneta carried out his wishes for the next year and a half, except for one thing: he did not dismiss General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, whom Gómez thought was conspiring against him. On June 13, 1953, Gómez tried to return to office, and a coalition consisting of moderates from both parties and the armed forces deposed him. They did it because they thought this was the only way to end the violence. Gómez fled to Spain, and General Rojas Pinilla asked Urdaneta to stay on as president, because he had experience in the job; Urdaneta declined and Rojas Pinilla assumed the presidency.

To bring peace as soon as possible, Rojas Pinilla offered unconditional amnesty to all combatants who returned to civilian life. Thousands accepted the offer, except for the communists, who did not trust Rojas Pinilla and went on to lay the groundwork for the guerrilla movements in Colombia today. Meanwhile, Rojas Pinilla transferred the National Police to the armed forces to depoliticize it, relaxed press censorship, and released political prisoners. Because it was the government's refusal to allow social reform that had polarized the country in the first place, Rojas Pinilla launched an extensive series of public works projects to help the poor, and introduced reformist measures like giving women the right to vote.

The honeymoon between Rojas Pinilla and the rest of the nation lasted less than a year. By the end of 1953, it was clear he was not going to put the old political system back together, but instead establish his own dictatorship, with a cult of personality and a populist program. In other words, he was imitating Argentina's Juan Perón. In addition, he allowed hired assassins, Conservative vigilantes, and members of the army and police to seek out and kill guerrillas who had already accepted amnesty. Because of that, former guerrillas left their farms to rejoin surviving units, La Violencia was resumed, and Rojas Pinilla responded with strict measures, starting with a hefty increase in police and military budgets. Several of the country's leading newspapers, both Liberal and Conservative, were closed. A new law put a fine or prison sentence on anyone speaking disrespectfully of the president, and a new constitution created a legislature in which the president appointed twenty of the ninety-two members. Atrocities mounted; one of the most notorious was the 1956 "Bull Ring Massacre," where the president's henchmen killed 8 and injured 112 spectators for failing to cheer Rojas Pinilla with enough "vivas." And if that wasn't bad enough, falling coffee prices, combined with inflation caused by government spending, threatened to undo the economic gains made since World War II.

In early 1956, the Liberal and Conservative elites decided that Rojas Pinilla had become more dangerous to them than they were to each other. While still in exile, former president Gómez signed an agreement with Alberto Lleras Camargo, the current leading Liberal and the first secretary-general of the Organization of American States; however, the moderate Conservatives stayed with Rojas Pinilla for now. Then in 1957, two more agreements were signed, this time with all Conservative and Liberal factions participating. The three agreements called for a coalition government, henceforth called the National Front, which would restore the 1886 constitution, share power 50-50 between the two parties, and rotate the presidency between them every four years.

Back in Colombia, Rojas Pinilla ordered the arrest of Guillermo León Valencia, one of the Conservative leaders in the National Front; student demonstrations, strikes and riots broke out, and then the Church and top-ranked military officers turned against him. Under pressure from all these folks demanding his resignation, Rojas Pinilla quit in May 1957, and a five-man junta took over. At the end of the year, Colombians voted overwhelmingly in a national plebiscite to approve the agreements the elites had already made in the previous paragraph. Elections were held in 1958, and because the Conservatives split along moderate and reactionary lines, the Liberals won the first round, and Lleras Camargo became the first president under the National Front. Thus, Colombia now had a democracy run by the elites of the two major parties, with no effective opposition.

The National Front held together for sixteen years, until 1974. President Lleras Camargo issued another amnesty in 1958, promising a pardon for all guerrillas who laid down their arms during the next year. Some guerrillas and other outlaws continued to operate on a low scale, but the country became stable enough that the 1958 elections marked the end of La Violencia. Also in 1958, Lleras Camargo introduced an austerity program to improve the economy, with immediate results; in 1958 Colombia recorded its most favorable balance of trade in twenty years. Still, there were difficulties, caused by the need for bipartisan support to get anything done (and gridlock when they didn't agree), and the contradictions produced in national policy by constant switching between Liberal and Conservative administrations. The overall score was mixed; while progress was made in some sectors, social and political injustices continued elsewhere.

Venezuela: Back In the Barracks

The leader of the three-man junta established after the 1948 coup, Carlos Delgado Chalbaud, had been in the 1945 junta, and was Minister of Defense under Gallegos. He promptly backpedaled by voiding the 1947 constitution, brought back the 1936 one, and outlawed the AD. Delgado was assassinated two years later, in 1950; whoever was behind the assassination was never caught. A lawyer, Germán Suárez Flamerich, was brought into the junta as a caretaker leader, and then the junta agreed to allow elections in 1952. When early election results showed another party (one supported by the AD) was running far ahead of the government party, one of the junta members, Marcos Evangelista Pérez Jiménez, ordered the count halted and declared himself president. The other junta members were sent abroad "on vacation," so the country was under the thumb of a caudillo again.

By now Venezuela was notorious for providing the best examples of Latin American dictators, and Pérez Jiménez was cast from the same mold as the others; he was born and raised in the mountains of Táchira, to start with (see footnote #19). Whereas Juan Vicente Gómez had talked about "Democratic Caesarism," Pérez Jiménez called the same doctrine the "New National Ideal," declaring that Venezuelans should stay away from politics and commit themselves fully to material progress. His opponents declared that he was just as brutal as Gómez had been. Political power was concentrated around Pérez Jiménez and six colonels from Táchira, and a restrictive new constitution brought back indirect elections by a puppet legislature. Strict controls were put on the press, labor unions were harassed, and when opponents of the regime appeared at the Central University of Venezuela (remember the Generation of 1928), the university was shut down. A vast National Security Police network rounded up hundreds, maybe thousands of opponents, and tortured or murdered them at the Guasina Island concentration camp in the Orinoco jungle.(95)

Oil revenues continued to increase every year, and Pérez Jiménez plowed much of it into public works projects. Some of the projects--highways, blocks of apartments for workers in the suburbs of Caracas, a major power and steel plant on the Caroni River, and an irrigation dam on the Guárico--were useful to the people, but the most visible ones were little more than monuments to the dictator. Examples of these included a replica of New York's Rockefeller Center, a luxurious mountaintop hotel on Mount Ávila, and the world's most expensive officers' club. Even worse than the unneeded projects was the corruption; as much as 50 percent of the state treasury may have been wasted or stolen. At the same time, by keeping the taxes on the oil companies low and maintaining a strong anti-communist policy, Pérez Jiménez won friends abroad; e.g., US President Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded him the Legion of Merit in 1954.

Stories of the insatiable greed Pérez Jiménez had for money and power turned the country against him, including much of the military (navy and air force officers resented him giving preferential treatment to the army). When his term in office ended in 1957, he pulled a shameless electoral trick. Elections were canceled, and instead he held a plebiscite in which voters could only choose between voting "yes" or "no" to another term for the president. Only two hours after the polls closed, the government announced that Pérez Jiménez won with an unbelieveable 85 percent "yes" vote, suggesting that the count had been rigged anyway.

The entire population cried foul at the plebiscite, and on the first day of 1958, the air force bombed Caracas. Although the expected coup did not materialize, three weeks of strikes and demonstrations followed; during that time, 300 were killed and 1,000 were wounded in street fighting. When the navy revolted, a group of army officers, fearing for their own lives, forced Pérez Jiménez to resign, and he fled to Miami with an estimated fortune of $250 million.(96)

A provisional junta took over after Pérez Jiménez left, and its biggest priority was to make the country financially solvent, so it stopped work on most of the ex-dictator's projects, and raised both income and oil taxes. Elections were scheduled for December 1958, and the long-time people's favorite, Rómulo Betancourt, won with 49 percent of the vote; the AD also won majorities in both houses of Congress. Betancourt was still a liberal, but this time he acted more cautiously than he had the first time he was president, and cooperated with the armed forces, instead of ignoring them. Although he had not answered the question of how to pass reforms by the parliamentary method if the military does not approve, otherwise his policies paid off, because he actually completed a five-year term in office--the first elected Venezuelan president to do so. Thus, for Venezuela anyway, this chapter will end on a happy note.

|

|

|

In the twentieth century, British Guiana's resources were sugar, rice and bauxite, and Dutch Guiana had rubber, gold and more bauxite. Britain restricted bauxite mining in British Guiana to British and Canadian companies, while the bauxite in Dutch Guiana was mined by the US company Alcoa, providing the United States with as much as 75 percent of its aluminum. Because the Netherlands fell under Nazi rule during World War II, on November 23, 1941, with the permission of the Dutch government-in-exile, the United States occupied Dutch Guiana to keep the bauxite mines in Allied hands. After the war, in 1954, the Netherlands granted autonomy to Dutch Guiana, retaining only control over defense and foreign policy.

France was also under Nazi occupation for much of the war. At first the government of French Guiana sided with Vichy France. However, there was considerable support for Charles de Gaulle and the Free French, and those who preferred the Allies over the Axis succeeded in changing the government to a pro-Free French one on March 22, 1943. Then three years later, in 1946, France declared French Guiana an overseas département. This made the colony equal in status to the districts and regions of France itself, very much like what happened when the United States granted statehood to Hawaii. However, there were no moves toward self-government, because nobody asked for it.

We mentioned in the previous chapter that France closed the Devil's Island prison in 1953. Even so, horrified visitors reported in December 1954 that the prison was still in use. Prisoners who had gone insane were kept there; conditions for them were almost as bad as when they were doing their time, and screams from them were heard constantly. The cellblock's only windows were small ventilation slots in the wall just under the roof; those in charge pushed in food once a day and removed bodies at the same time.

In British Guiana, the colonial government had been investigating and applying constitutional reforms since 1938. In 1953 a bicameral legislature was established, and the governor and other existing colonial officials were enrolled in a Court of Policy. In addition, universal suffrage was granted, and property qualifications for office were abolished. But when elections were held for the lower house of the new legislature in the same year, they sparked a crisis, because a left-wing group, the People's Progressive Party (PPP), won 18 of the 24 available seats. Fearing that the PPP was pro-communist, the British Government suspended the constitution, declared a state of emergency, and put British Guiana under martial law. This arrangement lasted until 1957. Obviously, by 1957 the British were less scared about who their Guyanese subjects might vote for; when elections were held again in 1957, the PPP won nine of fourteen elective seats in a new legislature.

The Cuban Revolution

One of the opponents of Fulgencio Batista's dictatorship was a young lawyer named Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (1926-2016). The son of a successful immigrant farmer and a servant girl in Oriente Province, his father had him baptized at the age of eight so he could attend Catholic schools. Ultimately he went to El Colegio de Belén, a famous Jesuit high school in Havana, where he was known as a good athlete, but not for his academic achievements.(97) He graduated in the same year (1945) and then went to the University of Havana, where he studied law and got his first exposure to stormy Cuban politics. In 1947 he joined an expedition of Dominican exiles and politically-minded students, who were planning to invade the Dominican Republic and overthrow that nation's dictator, Rafael Trujillo. However, the current Cuban government found out and arrested many of the expedition's members before they could sail between the islands; Castro was not among those arrested.

Castro's first chance at a political career failed because of Batista. In 1952, as a member of the populist Partido Ortodoxo, he ran for a seat in the Cuban Chamber of Representatives, and did not win because Batista suspended the elections with his coup. Castro's first reaction was to circulate a petition declaring Batista's government illegitimate because it was not an elected government, but the courts simply ignored this and all other legal challenges. Because of that, Castro decided to use armed force against Batista in the future; over the next year he and his brother Raúl (1931-) recruited 1,200 supporters in an anti-Batista rebellion that was simply called "The Movement." At the end of the 1940s, Fidel Castro read the writings of Marx, Engels and Lenin, which had radicalized his political views, but he was not yet ready to declare himself a Communist. That would have scared away potential recruits who had moderate political views, and at this stage he was willing to take anybody who opposed Batista. However, Raúl Castro considered himself a Communist from the early 1950s onward.(98)

Fidel Castro began his revolution with a raid on the Moncada Barracks near Santiago de Cuba, on July 26, 1953. The plan was to have 165 men sneak into the base disguised in army uniforms, steal weapons and ammunition, and leave before reinforcements could arrive. In the nineteenth century, rebels against the Spanish government had supplied themselves this way, but this time the tactic failed badly. Three of the sixteen cars used to transport rebels to the barracks never made it, the alarm was raised when the rest got there, and most of the rebels never entered the base, being pinned down by machine gun fire at the gate. When the fighting ended, nineteen soldiers and six rebels lay dead. Batista declared martial law, and the army rounded up the surviving rebels over the next few days. Many prisoners (though not the Castros) were tortured, mutilated, and/or murdered before they could stand trial. When the trial did take place, Fidel acted as his own defense attorney, and turned the trial into an embarrassment for the Batista administration, by revealing its atrocities against the prisoners. He made long speeches until the government tried to keep him out of the courtroom by claiming he was too ill to leave his cell, but the few reporters allowed to attend made sure word got out about the trial's proceedings. The last speech went on for nearly four hours and ended with the words, "Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me." This gave Castro national attention and made him a hero to many poor Cubans. Likewise, the July 26 raid on Moncado would be remembered as a defeat which later led to victory, much like how Texans remember the battle of the Alamo.

While more than half of the defendants at the trial were acquitted, Fidel and Raúl got long prison sentences on the Isle of Pines. Then in 1955, the Batista government came under international pressure to clean up its act, so it released many political prisoners, including the Castro brothers, in a general amnesty. Fidel and Raúl moved to Mexico, seeking new recruits and guerrilla training for The Movement, now renamed the "26th of July Movement" in memory of their first attack on the regime. While in Mexico, they received money from former Cuban president Prío. They got the training they wanted from Alberto Bayo, an exile from Spain who had been one of the Loyalist commanders in the Spanish Civil War. Among the new recruits they found, the most important were a Cuban exile named Camilo Cienfuegos and an Argentine medical school graduate named Ernesto "Che" Guevara.(99) When he wasn't studying, Guevara had traveled around Latin America, saw poverty and misery everywhere, looked for a way to do something about it, and got caught in Guatemala during the failed revolution of Jacobo Árbenz. Now when he joined the Cuban revolution, he became a rebel with a cause, the 26th of July Movement's doctor, and eventually Fidel Castro's right-hand-man.

For the return trip to Cuba, Fidel Castro purchased a small, run-down yacht, the Granma. The boat was not designed to carry more than twenty people (eight crew + twelve passengers), but when they left the Mexican port of Tuxpán, eighty-two rebels were crowded aboard. Still, that meant leaving fifty others behind; later it was said that Cienfuegos was allowed to go because he was the skinniest in the group. After a dreadful, week-long voyage (November 25-December 2, 1956), they made it to Cuba's southeastern coast, the traditional landing place for rebels.

The landing was a classic comedy of errors. Castro had instructed allies in Santiago de Cuba to launch an uprising to distract the army from his arrival, and predicted it would take five days to sail from Mexico. But as we saw, the trip took seven days, due to the Granma having engine trouble and being overloaded, so the uprising happened two days before Castro's landfall. On top of that, they landed on a beach fifteen miles away from the beach he had targeted, and because Batista's forces spotted the Granma from the air beforehand, they were ready for him. Consequently several rebels were killed on the beach, and more were lost in running battles over the next few days. Castro had chosen to make the Sierra Maestra, the mountains running along that coast, his base of operations, but by the time he made it there, he only had twelve of the original eighty-two men left; Raúl, Cienfuegos and Guevara were among those twelve. Even so, when they arrived in the mountains, Castro asked a peasant, "Are we already in the Sierra Maestra?" The peasant said yes, and he optimistically declared, "Then the revolution has triumphed."

What happened next sounds more like a story from fiction than a real-life event. Whereas most Latin American revolutions are started and led by military men, and the rest are peasant uprisings, the twelve survivors were strictly urban radicals, with no military training or experience in living in the countryside--and they were taking on the armed forces of an entire nation. Moreover, their opponent had plenty of money, an effective secret police, and the grudging support of the United States. Yet they managed to survive and attract recruits until they ultimately won.(100) And throughout the struggle the revolutionaries were always outnumbered; Castro's guerrilla army numbered only eighty men in the spring of 1957, 300 in mid-1958, and barely 3,000 at the final victory.

On Pico Turquino, the highest mountain in in the Sierra Maestra (elevation 6,000 feet), Castro had a radio station built, Radio Rebelde, which carried his message far behind enemy lines and let everyone know he was still alive, despite government claims to the contrary. The trees and valleys of the mountain range gave the revolutionaries plenty of places to hide from aircraft, while the soldiers, not willing to engage the revolutionaries in close combat, tried without success to surround Castro's base. By using the hit-and-run attacks that always work best for guerrillas, Castro won more often than he lost, and gained the support of the peasants in Oriente Province. Meanwhile in the cities, opponents of Batista, most of them not connected with Castro's group, staged strikes and acts of terrorism. On March 13, 1957, the Revolutionary Directorate (RD), a group of anti-communist students, stormed the presidential palace in an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Batista. The RD leader, José Antonio Echeverria, was among those killed; the survivors escaped to the Escambray Mountains in the middle of the island. There they became the 13th of March Movement, and helped Castro's group by defeating the local pro-Batista forces.

The government response to all this unrest was so brutal that the United States cut off arms shipments to the government in March 1958. Around the same time, the Cuban middle class abandoned the dictator as well. In the summer of 1958, Batista went for a make-or-break move, sending a large part of his army into the Sierra Maestra to flush out Castro once and for all. Instead, the nimble rebels gave the army the slip again, and struck back at the soldiers until many of them switched sides or deserted.

After that, the Batista government collapsed from within. While a US envoy urged Batista to leave the country, he actually held a presidential election, hoping to establish a new government that the United States would recognize and support. Of course it wasn't a fair election; Batista printed filled-in ballots in advance, and had a puppet president ready to begin his term in February 1959. But the revolutionaries got to Havana first. In December 1958, after spending two years in Oriente, the 26th of July Movement broke out of that province. Fidel Castro sent one group of fighters with Raúl to capture the northeast coast, and three columns (led by Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos and Jaime Vega) charged west, following the Central Highway. Government forces ambushed and destroyed Jaime Vega's column, but the other two columns reached the Escambray Mountains, joined up with the 13th of March Movement, and after Cienfuegos won a key battle at Yaguajay, they captured Santa Clara, the provincial capital. Next the barbudos ("bearded ones") made a beeline for Havana.

On January 1, 1959, Batista and his closest associates grabbed whatever loot they could take with them, and fled Cuba. This time he would not return, staying in exile until his death in 1973. Today Batista is all but forgotten; most people simply remember him as "the guy Fidel Castro threw out."(101)

Six members of the 26th of July Movement wave a banner as they celebrate victory.

Back in Cuba the people took to the streets, welcoming the rebels as they reached every city and town. Cienfuegos, Guevara and their men entered Havana on January 2, one day after Batista left, and disarmed the remaining soldiers. Fidel Castro stayed behind in Oriente to take Santiago de Cuba, the city that had defeated him in 1953, and then he went west, entering Havana in triumph on January 9.

The narrative for this chapter ends here, and if Fidel Castro's story had ended here, it would have been well and good. But his success had made him a role model for a generation of rebels around the world. Unfortunately for them, conditions were not right to duplicate the Cuban example in most countries (see the last footnote); nowhere in Latin America was a government as universally detested as the Batista regime in 1958. Twenty years later in Nicaragua, the Sandinistas would successfully carry out a Cuban-style revolution; elsewhere the typical revolutionary was a young loser, likely to be in exile from his homeland.

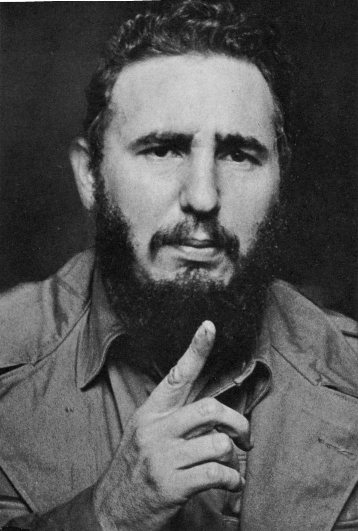

Castro and Che wannabes should also remember what happened in Cuba after the Castro brothers won; they exchanged a despiccable right-wing dictatorship for a despiccable left-wing dictatorship. The months following their victory saw a bloodbath; Raúl Castro and Che Guevara were put in charge of the squads that imprisoned and executed former Batista supporters. Although they eventually allowed the 13th of March Movement and some socialists to join the Communist Party, the Castros turned against the other rival rebel groups that had helped them come to power, once they ran out of enemies to persecute. Hundreds of thousands of middle and upper class Cubans fled to the United States and Mexico, forming the largest ethnic group in Miami, Florida. And because Raúl Castro is alive at the time of this writing, we cannot say the story of the Cuban Revolution is over yet. At this date, the revolution looks like a prime example of the cure being worse than the disease.

Fidel Castro, at the end of the 1950s.

This is the end of Chapter 5.

FOOTNOTES

86. Schlesinger, Arthur M., A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, New York, Houghton Mifflin (2002), pg. 216.

87. http://archive.frontpagemag.com/readArticle.aspx?ARTID=26996

88. From 1898 to 1932, the island's name was given an Anglicized spelling = Porto Rico.

89. Having non-native Anglos from the mainland running the entire Puerto Rican government caused multiple misunderstandings. The worst, now called the Ponce Massacre, involved the Nationalist Party; in 1937 the Nationalists held a parade to celebrate 100 years since Spain abolished slavery on the island, and the police killed nineteen of them in an unprovoked attack.

90. Today the anniversary of Vargas' suicide is an unofficial Brazilian holiday. Each year on August 24, the newspapers will devote several pages to the former president's life. Likewise, most Brazilians choose to remember his social welfare programs and forget his dictatorial rule.

91. Naturally the residents of Rio de Janeiro were unhappy at their loss of status, when the capital moved to Brasília. Some critics call the Federal District "ilha da fantasia" ("fantasy island"), because here the builders created a Utopia, while the rest of Goiás remains poor and underdeveloped.

92. In European history, Benito Mussolini took over Italy and held onto power with a goon squad called the Blackshirts. Likewise, Adolf Hitler's goons were the Brownshirts, British troops in early twentieth-century Ireland were the "Black and Tans," and we saw that Mexico had a right-wing goon squad, the Gold Shirts, in the 1930s. Decamisados was a name for the Argentine poor, meaning "shirtless," and because Perón used thugs from this social class in the same way as the others mentioned here, you could call them the "No Shirts."

93. In this work we have covered the strange stories of Christopher Columbus and Gabriel García Moreno after their deaths. Well, Evita had a post-mortem adventure, too. Her devastated husband brought in an expert embalmer from Spain, who did such a good job preserving her body that Perón wanted to put it on permanent display, the way the Soviet Union did with Lenin. After the funeral, which was attended by nearly three million people in the streets of Buenos Aires, Perón began building a suitably grand memorial to her, but he was overthrown before he could finish it, and left the body behind when he fled. The post-Perón government, deciding it was not safe to have Evita around, sent the body to Milan, Italy, where it was placed in a crypt under a fake name. Sixteen years later, in 1971, they revealed where the body was; Perón recovered the body, and because it was still in good condition, he put it on display, on a platform in his dining room. Since Perón had already remarried, his final wife, Isabel, must have been incredibly understanding (and she must have had a strong stomach, too!). When Perón returned to Argentina, he brought the body back with him. After his own death, both bodies were displayed side-by-side until the funeral, and then they were buried in separate cemeteries of Buenos Aires, presumably their final resting places.

94. When La Violencia peaked, both before and after the 1953 coup, there were an estimated 20,000 guerrillas at large.

95. The chief of police was an especially cruel and notorious fellow, Pedro Estrada. Costa Rican President José Figueres Ferrer called him "the Himmler of the Western Hemisphere," while in The History of Latin America From the Beginnings to the Present, the historian Hubert Herring called him "as vicious a manhunter as Hitler ever employed." When US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles invited Estrada to visit Washington and meet with him (1954), the Venezuelan public was angered more by this than by the favorable treatment Washington gave to the president. Because of this, when US Vice President Richard Nixon visited Caracas in 1958, shortly after Pérez Jiménez was overthrown, anti-American protesters spat on him and stoned his motorcade.

96. Pérez Jiménez left behind an empty treasury, so naturally it was believed he took the money with him. In 1963 he was extradited back to Venezuela on a charge of embezzling $200 million. The trial was delayed until 1968, and though he was convicted, the sentence was commuted because he had done time in prison while waiting for the trial. Afterwards he was exiled again, and stayed in Spain for the rest of his life. A later dictator, Hugo Chavez, dropped the murder charges against him in 1999, and partially rehabilitated his image, because Chavez was an enemy of the two-party democracy that existed between the reign of Pérez Jiménez and his own.

97. In 1961, after Cuba had become Communist, the government confiscated the school's property, so its faculty moved to Miami, Florida, where the school's campus stands today.

98. Cuba's Communist party was founded in 1925, but before the Castros came along, it was too small to have much influence. During the first three decades of its existence it allied with stronger groups, e.g., supporting Machado in 1928 and Batista in 1940.

99. "Che" is not a real name or even a proper nickname. It's an Argentine idiom that more or less means "Hey there." He got called that because he said it all the time.

100. The only other revolutionary I can think of who had this kind of luck was Giuseppe Garibaldi, on his campaign to unite Italy.

Incidentally, Fidel Castro grew his trademark beard while he was camping in the Sierra Maestra; previously he was clean-shaven.

101. Today the only relic from Batista's rule that you are likely to see in Havana is the Christ of Havana, a 66-foot-high white marble statue of Jesus, overlooking Havana Bay. Batista's wife commissioned the sculptor Jilma Madera to create the work in 1953, figuring that it would persuade God to bless her husband and keep him in power for life. No such luck; the statue was completed on December 24, 1958, just eight days before the revolution forced Batista to flee the country. Though communists are notorious atheists, they left the statue alone, perhaps because the sculptor gave Jesus a Cuban face. Locals like to joke that the statue is missing two other Cuban features; it was meant to hold a cigar in one hand, and a mojito in the other!

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|