| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of the South Pacific

Chapter 5: Oceania Since 1945, Part III

Part I

| First, A Word on the Cargo Cults | |

| The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, and Nearby Atolls | |

| Australia: The Menzies Era | |

| Rabbits Gone Wild | |

| Recolonial New Zealand |

Part II

| Independence Comes to the Islands | |

Part III

| The Australian Constitutional Crisis | |

| Australia in Recent Years | |

| New Zealand: Labour and National Reforms | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part IV

| The Smaller Island Nations Since Independence | |

| Conclusion for the Islands |

The Australian Constitutional Crisis

Robert Menzies retired in 1966. Four prime ministers followed him over the next six years. Three of them, like Menzies, came from the Liberal Party; the fourth, John McEwen, was from the Country Party. For all four, the main objective was to continue the prosperity the Menzies administration brought to Australia.

At the same time the Australian public, influenced by the creation of dozens of new Third World nations, and the Civil Rights movement in the United States, came around to the idea that the Aborigines were people too, and should be treated as such. Up to this point, the Aborigines had not been citizens of their own country; for land ownership purposes, the law had declared Australia Terra Nullius (“nobody’s land”), meaning the continent was empty before European settlers arrived. Aborigines were not counted in censuses, meaning their status was even lower than that of slaves in the Antebellum United States (the Americans counted each slave as 3/5 of a person, when calculating how many congressmen would represent each state), and only the handful that served in the Australian armed forces during the two World Wars were allowed to vote.

In the early twentieth century, the government’s policy was to protect the aborigines by keeping them isolated from modern society. Then in the 1940s, “protectionism” was replaced by a policy of assimilation, which declared that Aborigines could only survive in the modern world if they were totally immersed in white Australian culture. The most notorious part of this policy was the program that took Aboriginal children from their families, even when nothing was wrong with the parents, and sent them off to be raised by white families or church-run institutions, to make sure the right culture was programmed into them. A recent national report on the assimilation policy found that at least one child was taken away from every indigenous family; Aborigines will now sometimes refer to the years from the 1940s to the 1970s as the Stolen Generations.

Though the government may have had good intentions when it implemented first protectionism, and then the assimilation policy, life did not get better for the Aborigines under either. The status of Aborigines remained low in modern society, they were paid less than white Australians doing comparable work, and their roles in World War II and the development of the outback usually went unrecognized.

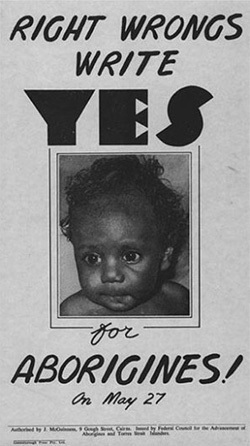

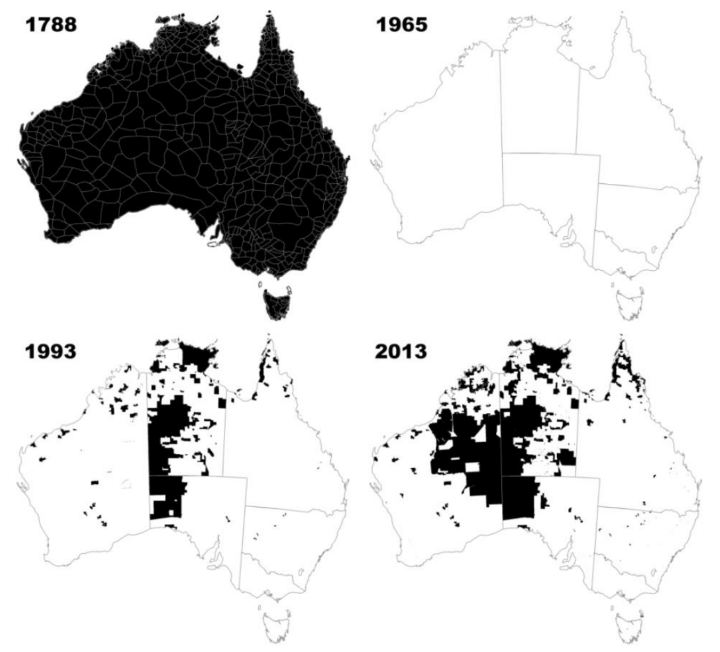

Some effort was made in the closing years of the Menzies administration to give the Aborigines more rights, but the real breakthrough came in 1967, when voters were asked whether they favored the removal of wording from the constitution that discriminated against Aborigines. They overwhelmingly voted “Yes”; 90.77% approved the amendment. With that, the White Australia Policy was declared dead, and it would be officially buried by the Whitlam government in 1973.

A campaign poster from the 1967 referendum. Using pictures of cute kids has always been an effective campaign strategy. Source: Righting wrongs in the 1967 referendum.

For the Aborigines, their situation has improved slowly since 1967. In 1972, for instance, they were given back limited rights to their land. However, in all statistics regarding health, education and economic well-being – from life expectancy to income, they are still worse off than other Australian citizens, so just about everyone agrees that more needs to be done.(23)

Since the white man arrived in 1788, the Aborigines first lost their land, then regained part of it.

Finally, in the late 1960s-early 1970s, there was a feeling among young people, artists and intellectuals that Australia had become a rather boring country, a southern hemisphere imitation of the United States and United Kingdom. One thing that they did about it was launch a cultural blooming, a new wave of nationalism. This period saw the establishment of the Australian Council for the Arts, the Australian Film Development Corporation and the National Film and Television Training School. A new TV show about a boy and his pet kangaroo, “Skippy the Bush Kangaroo,” became popular worldwide. The most famous building in Australia, the Sydney Opera House, was built at this time, and opened in 1973. “Advance Australia Fair,” the current Australian national anthem, was adopted in 1984, replacing the British anthem “God Save the Queen.”

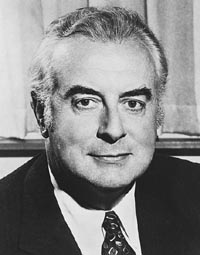

The other thing Australians did to make things more interesting was elect a Labor government in 1972, the first in twenty-three years. Edward Gough Whitlam, the new prime minister, campaigned using the motto “It’s Time,” meaning everyone had waited long enough for Labor to have a turn at running the ship of state. He was tall, handsome, a brilliant lawyer, an excellent orator – and full of ideas about how he wanted to reform Australia. As soon as he was in charge, Whitlam ended military conscription, and pulled the last Australian military advisors from Vietnam.(24) Full diplomatic relations were established with the People’s Republic of China, and since Australia couldn’t be friends with China and Taiwan at the same time, the embassy on Taiwan was closed. On the home front, Whitlam made university education free, and introduced universal health care, no-fault divorce, and equal pay for women.

Gough Whitlam.

Unfortunately, like government programs elsewhere, most of Whitlam’s innovations came with a price tag, and because the Labor Party did not control the Senate, he had trouble securing funding. Spending bills were voted down, sometimes more than once. At the same time, rising oil prices led to inflation and a recession, eroding Whitlam’s popularity. The Australian media turned against him, too, because in those days the media did not enthusiastically support any leftist politician, the way it does now. Things got to the point that the Whitlam government considered borrowing US$4 billion from lenders in the Middle East, a violation of the constitution. Rex Connor, the Minerals & Energy Minister, conducted secret negotiations with a mysterious Pakistani banker, while the Treasurer, Dr. Jim Cairns, misled Parliament about what was discussed; though no loan was secured, both ministers would lose their jobs over the “Loans Affair.”

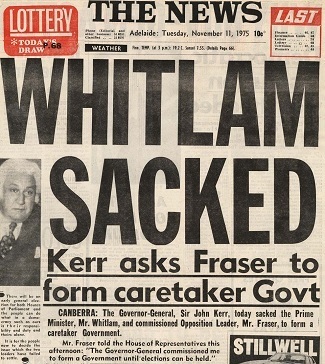

After this, the Liberal-Country coalition in the Senate, led by Malcolm Fraser, declared that the government was incompetent, and refused to pass any more spending bills until new elections were held. This resulted in what Americans call a “government shutdown.” The one person in Australia who outranked the prime minister was the governor-general, Sir John Kerr; he could break the gridlock, and pressure was put on him to act for this reason. On November 11, 1975, Whitlam first held a meeting with Fraser that resolved nothing, and then the governor-general called Whitlam to his office. Whitlam probably expected Kerr would be on his side, because he had appointed Kerr to the governor-general position a year earlier, but instead Kerr sprung a surprise, dismissing Whitlam and declaring Fraser the acting prime minister. When this was announced, the only reason given for Whitlam’s firing was “failure to perform.” Fraser immediately passed a spending bill to keep the government running, and Whitlam, now the opposition leader, went to the House, where he still had support, and filed a no-confidence motion to stop Fraser. Kerr responded by dissolving Parliament, just three hours after he had fired Whitlam. Since the governor-general’s job was to represent the King or Queen of England in Australia, you could say that Queen Elizabeth II had just fired the entire Australian government; even in today’s world, a monarch can still beat an elected politician.(25)

Coincidentally, all this happened on a holiday, the anniversary of the end of World War I, so now Australians had two things to remember on “Remembrance Day.”(26)

How the people of Adelaide found out that Whitlam was fired.

The public’s initial reaction to Whitlam’s dismissal was to launch massive protests in his favor. The crowds which turned out for these demonstrations were larger than those which had supported Whitlam during election campaigns; their favorite slogans were “We Want Gough!” and “Shame Fraser Shame.” With Parliament dismissed, the election Fraser wanted now had to be held. When the election took place in December 1975, the Liberal-Country coalition won by a landslide, gaining commanding majorities in both houses of Parliament; that ended the pro-Whitlam demonstrations in a hurry.

Australia in Recent Years

Once Malcolm Fraser became an elected prime minister, he restored the domestic and foreign policies followed by the earlier Liberal Party governments. Then in 1976, Parliament passed the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, which recognized that the Aborigines had an “inalienable” title to traditional lands in the Northern Territory. When new elections came in 1980, Fraser’s coalition survived, but it held a much smaller majority. However, a recession in the early 1980s, aggravated by a drought, caused him to lose the next election, in 1983.

The new Labor Party prime minister, Bob Hawke, was a less polarizing figure than Whitlam. Hawke did well enough that he was still prime minister when 1988 rolled around; for Australians that was a holiday year, as they celebrated the bicentennial anniversary of the Botany Bay colony, and the opening of the New Parliament House (see the previous footnote). Like previous Labor leaders, Hawke believed the government can and should intervene to stimulate the economy, but unlike Whitlam, he practiced a strongly pro-American foreign policy. That was put to the test in 1990, when Hawke committed Australian naval forces to the coalition that drove Iraqi forces out of Kuwait, in Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm. Labor won three elections while Hawke was in charge (in 1984, 1987 and 1990), but then another recession struck at the beginning of the 1990s, causing his popularity to drop, so in December 1991, Labor chose Hawke’s former Treasury Minister, Paul Keating, to replace him as party leader and Prime Minister.

Keating came in promising to change Australia into a US-style republic, and talked about the need to give more attention to Asian and Pacific nations, especially Indonesia. Under him, Aboriginal relations took more than one step, with the Eddie Mabo decision in 1992, the Native Title Act in 1993, and the Land Fund Act in 1994. These acts struck down the Terra Nullius doctrine, and declared that human remains, and sites that were of sacred or historic importance to indigenous Australians, were under the full control of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.(27) Thus, all museum collections had to be returned if they requested them, and control over more land was transferred, too.

The Labor Party under Keating won the 1993 election, but then was defeated in the next one, in 1996. John Howard of the Liberal Party now became prime minister, ending thirteen years of Labor rule. Howard was one of the most successful prime ministers in recent years, and it shows in how he won four elections (1996, 1998, 2001 and 2004), and remained in office for eleven years. In 1998 he followed up on Keating’s promise to modify the government by convening a constitutional convention. This body proposed replacing Queen Elizabeth II as head of state with a president chosen by Parliament, but when it was put in a referendum, Australians voted it down; 55% chose to leave things the way they are. Howard was also in charge when Sydney hosted the highly successful 2000 Olympic Games (see footnote #5), and Australia celebrated the 100-year anniversary of its independence (2001).

Howard is mainly remembered for his active foreign policy. In 1999 Australia led the UN peacekeeping force that ended the fighting in East Timor, between the natives and the Indonesian armed forces. This allowed East Timor to become independent, and it strained Australian-Indonesian relations, but the Indonesians later forgave Australia because it was one of the countries that sent aid and rescue workers, following the terrible tsunami of December 2004. Australia headed other peacekeeping forces as well, to Bougainville in Papua New Guinea in 1998, and to the Solomon Islands in 2003. And when the United States fell victim to the major terrorist attack on September 11, 2001, Howard happened to be in Washington, DC. Consequently Australia invoked the ANZUS treaty to become an enthusiastic member of the “Coalition of the Willing”; in Afghanistan and Iraq, Australia contributed the third largest contingents of men and materiel, after the United States and Britain.(28) However, at the same time Australia was criticized for its policy of detaining refugees indefinitely in camps, like the one on Nauru (more about that in the Nauru section).

The winning streak of John Howard ended with the elections of November 2007, when the Labor Party, led by Kevin Rudd, won a landslide victory. Rudd was less interested in the outside world, and more interested in the environment, education and health care. One of his first acts was to sign the Kyoto protocol on global warming, something Howard had opposed. However, the Senate rejected the carbon emissions tax that would have been used to enforce the protocol, and Rudd lost his popularity when he tried to introduce a tax on mined minerals in the middle of a recession. Rudd was compelled to resign in 2010, and his replacement, Julia Gillard, was Australia’s first female prime minister.(29) Gillard immediately called for new elections, which no party won, so she stayed in office by forming a minority government coalition with independent members of Parliament. In 2012 she brought back the controversial carbon tax, saying big polluters had to be penalized to meet the terms of the Kyoto protocol, while opponents warned it would get rid of jobs and cause inflation.

Rudd may no longer have been prime minister, but he wasn’t gone from the political scene. For several months in early 2013, the Labor Party saw infighting between Gillard and Rudd, until Rudd got Labor leadership to reinstate him. However, Rudd’s second term as prime minister only lasted three months; the September 2013 election was a landslide Liberal victory. Tony Abbott took charge as the new Liberal prime minister, and he held the job for two years, when the Liberal Party leadership replaced him with the current prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull. Turnbull is holding on with the narrowest of majorities as I upload this chapter.

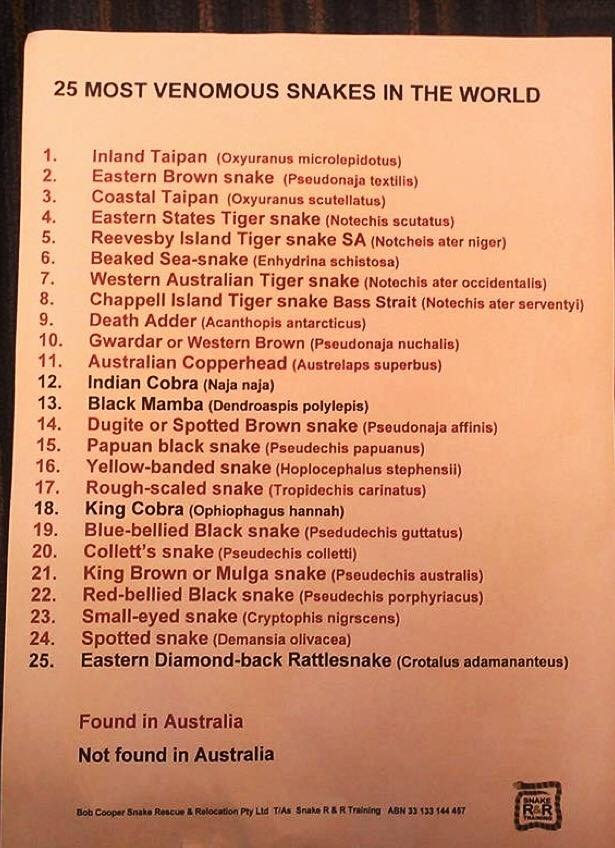

Australia has come a long way in a little over two centuries. In the beginning it was a continent full of strangerous, dangerous animals (e.g., see the above list), and the world’s largest prison. It couldn’t have looked like a very promising place in those days, but today it is arguably the most successful nation in the southern hemisphere, and it is certainly the biggest success story in the South Pacific. You know it is a fully modern nation because the issues facing Australia at this time are the same as those facing other Western nations: a weak economy, unpopular politicians, same-sex marriage, climate change, and refugees/immigrants trying to get in from the world’s trouble spots. In the past I would have expected the Aussies to do whatever the British or Americans did about those problems, but nowadays they’re more likely to try their own solution. Whatever else you can say about Australia, it’s a trendsetter nation now.

Some Australians resent their country being called “Down Under” by people living north of the equator, and have called for maps and globes that put the southern hemisphere on top, instead of the northern hemisphere. The artist behind this picture felt that way. The picture came from the box for a silly 1980s science fiction game. “Hunter Planet: The All Australian Role Playing Game” is about what happens when aliens come to earth to hunt humans, and they land in Australia, a place where their game can fight back.

New Zealand: Labour and National Reforms

New Zealand is to Australia what Canada is to the United States. Like Canada, New Zealand has a fraction of its neighbor’s population, and its people are quiet and polite most of the time, while the neighbor occasionally goes crazy. New Zealand ranks Number 9 on the world's Social Progress Index, meaning the rest of the world considers it one of the best places to live, and as we noted earlier in this chapter, becoming the backdrop for movies about Middle Earth was the best thing to happen to the country in recent years. Finally, like the Canadians, New Zealanders are concerned that the rest of the world see them as nice people. When the American news anchor Matt Lauer lost his job due to charges of sexual harassment, New Zealand reconsidered a decision from earlier in the year, which allowed Lauer to purchase a ranch in their country. You can think of Australia and New Zealand as a comedy duo, like Abbott and Costello; now that we’ve seen the funny man, let’s see what the straight man was doing at the same time.

The last time we looked at New Zealand in this narrative, it was under the Third National government, with Robert Muldoon as prime minister. Officially the National Party was the country’s conservative party, but in practice it followed a centrist policy. While it tried to preserve the straight-laced culture of the 1950s, it also tried to keep the “cradle to grave” welfare state that had been established in 1935, though critics predicted it would bankrupt the treasury. Unfortunately, the second wave of OPEC oil price increases in 1978-79 made sure that both the budget and the economy would be unbalanced. Attempting to prevent this by imposing a total freeze on wages, prices and interest rates didn’t work (it never does). On a positive note, the Treaty of Waitangi Act was passed in 1975; this established a tribune to examine Maori land claims. At first this only reviewed cases started since 1975, but under the next Labour government it began reopening old cases going all the way back to 1840, the date of the treaty it was named after.

By 1984, inflation and unemployment had gotten so bad that when elections were held, the Labour Party won by a landslide. Officially David Lange, the new prime minister, was the one in charge, but the finance minister, Roger Douglas, was the minister who got the most things done. Douglas introduced a wave of unexpected free-markets reforms that pleased conservatives, comparable to what Ronald Reagan introduced in the United States, and Margaret Thatcher introduced in Britain. This included removing wage/price controls, removing the link that kept the New Zealand dollar's value at the same level as the American dollar, cutting government spending, reducing most taxes and subsidies, and introducing a sales tax; together these policies were nicknamed "Rogernomics." As one political scientist put it, "Between 1984 and 1993, New Zealand underwent radical economic reform, moving from what had probably been the most protected, regulated and state-dominated system of any capitalist democracy to an extreme position at the open, competitive, free-market end of the spectrum."(30) The Fourth Labour government also introduced the Homosexual Law Reform Act (1986), which allowed homosexuals to come out of the closet; the Constitution Act (1986), which meant that laws passed by the British Parliament no longer applied to New Zealand; and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act (1990). Finally, immigration reform allowed more immigrants to come in from Asia and other Pacific nations. Thus, the Labor government of the 1980s has been compared with the Labour government of the late 1930s (see Chapter 4), which also passed a lot of reforms.

New Zealand became the scene of an international incident in 1985 when French secret agents sank the Rainbow Warrior, a ship belonging to the environmental activist group Greenpeace, while it was in Auckland’s port. The ship was on its way to protest a French nuclear test (see footnote #2), and one crewman was killed. New Zealand played no part in this affair, but it made headlines around the same time because the government declared the whole country and the surrounding waters a “nuclear-free zone.” This meant that US naval vessels could not enter New Zealand ports unless they declared they were not carrying nuclear weapons, and since they did not want to announce what armaments they had aboard, American warships were effectively banned from new Zealand waters. The Americans responded by suspending treaty obligations with New Zealand. New Zealand did not withdraw from ANZUS, though, so since the mid-1980s New Zealand has been the inactive ANZUS member.(31) However, New Zealand did contribute peacekeeping troops for East Timor in 1999, and sent 191 troops to Afghanistan in 2001.

One unfortunate consequence of the economic reforms was a wave of speculation overvaluing the stock market. The bubble burst in October 1987, a day investors call “Black Monday.” Whereas the American stock market recovered from this crash by early 1989, the New Zealand slump lasted until 1991, and that market lost 70% of its value; unemployment took a whole decade to return to pre-crash levels. First Douglas and Lange were both forced out of their jobs; then in 1990 the voters brought back the National Party.

For the Fourth National government, Jim Bolger served as prime minister from 1990 to 1997, and then Jenny Shipley, the first female prime minister, served from 1997 to 1999. Though the voters felt the government was enacting too many reforms, the National Party continued to introduce new ones. This time they were mainly another wave wave of spending cuts, called “Ruthanasia” after the finance minister, Ruth Richardson. More popular was mixed-member proportional representation, introduced in 1996 because of voter complaints about too many candidates getting elected who did not represent their views.

Labour got another turn in power in 1999, when voters elected a Labour-led coalition, this time led by Helen Clark. Unlike the previous Labour government, this one left the economy alone, and focussed its attention on social issues, like modifying employment law to give workers more protection, and making student loans interest-free. In 2008 Clark was succeeded by another National government, led by John Key, the current prime minister. So far the main event of this administration has been New Zealand’s worst natural disaster, an earthquake which devastated Christchurch in February 2011 and killed 185 people.

Like Australia, New Zealand has seen a great flowering of its local culture, but we cannot yet tell what form it will eventually take. The dominant trend we have seen in the past half-century is a cutting of the ties to Britain that were so important previously, replacing them with a closer relationship to Asia and the other South Pacific nations. In the government, for example, the main ties remaining are New Zealand’s Commonwealth membership and having the King or Queen of England as the ultimate head of state. At the same time, while the country finds its own path, it’s a safe bet the Kiwis will keep what they liked best from their past -- the pub, rugby, and especially their beautiful scenery, because both of their main industries (agriculture and tourism) depend on a clean environment. And it is likely the Maori will have a part in the country’s continued progress. If New Zealand can achieve all these things, it will remain one of the world’s model nations for years to come.

You have probably noticed that the New Zealand flag looks almost the same as the Australian flag; the main difference is that New Zealand uses red stars and Australia uses white stars. Because it is easy to get the flags mixed up, Prime Minister John Key announced a referendum in 2014 to vote on whether to replace the NZ flag with another design. No less than forty alternate designs were proposed. This picture shows four of them; ferns and koru (coiled fronds) were popular because these are Maori symbols. There were two rounds of voting, in late 2015 and early 2016. In the end the voters chose to keep the red-star design by 56.6%, so they left the flag the way it was.

This is the end of Part III. Click here to go to Part IV.

FOOTNOTES

23. The first Aborigine to join Parliament was Neville Bonner, who was appointed to the Senate in 1971; the first Aborigine elected to the House of Representatives was Ken Wyatt, in 2010. Interestingly, both of them belonged to the Liberal Party, though Labor claimed to be their champion. Sir Douglas Nicholls was appointed governor of South Australia in 1976, making him the first Aborigine governor.

The government’s Aboriginal policy has changed names more than once over the years. After dumping the assimiliation policy in 1972, Gough Whitlam’s Labor government replaced it with “self determination.” Then when the Liberals returned to power under Malcolm Fraser, he renamed the policy “self management” (1976). The policy got another, name, “self empowerment,” in 1996, and that name is still in use at the time of this writing. In practice, however, all three policies worked pretty much the same way.

24. Gough Whitlam had always opposed the Vietnam War. Within days of taking office, he sent a letter to US President Richard Nixon, criticizing the American bombing of North Vietnam, and strongly urging that the United States and North Vietnam return to serious negotiations. Nixon was so offended that he did not answer the letter, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called the Australian embassy in Washington to say that “we are not particularly amused [at] being put by an ally on the same level as our enemy.” After that, Nixon and Whitlam were not on speaking terms until July 1973, when Nixon reluctantly granted a one-hour meeting in the White House, without the usual frills that come with such a visit (no formal welcome, no speeches, no toasts, and no state dinner). During the Cold War era, a left-wing government in Australia was definitely something the Americans did not want. US-Australian relations remained at a low point until Whitlam’s ouster in 1975.

25. No, any Yankees reading this can’t employ the royal solution to fire American politicians, the next time there is gridlock between Republicans and Democrats. You see, the Americans had this little revolution to get rid of the British monarch, in 1776. Nor has the United States ever been a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, which made the whole process legal in Australia.

26. The old Parliament House building in Canberra is also called the Provisional Parliament House because when Parliament moved in (1927), they did not expect to use it for more than fifty years. Today Australians will tell you that the dismissal of Gough Whitlam was the most important event to happen there. By the late 1970s Parliament House had run out of room for all the functions and duties expected of Parliament, and the place needed repairs, so Malcolm Fraser’s government began the building of a permanent building for Parliament. The New Parliament House was opened in May 1988, a few months after the bicentennial, and since then the old building has been used for temporary exhibitions, lectures, and concerts.

27. As the name suggests, the Torres Strait Islanders live on fourteen of the 248 small islands between Australia and Papua New Guinea. They are ethnic Melanesians, meaning their closest relatives are on the New Guinea side of the strait, but they chose to remain with Australia when Papua New Guinea became independent. Today the tribe numbers 48,000, but only 6,800 of them are on the Torres Strait Islands; the rest are on the Australian mainland, mostly in northern Queensland.

While we are on the subject of indigenous populations, the Aborigines are believed to have stopped declining in 1933, when their numbers were estimated at 74,000. By 2010, the Aborigine population had grown to an estimated 563,000.

28. Islamic extremists struck back by bombing a nightclub on Bali in October 2002. Of the 202 people killed, 88 were Australian citizens. In 2004 terrorists attacked the Australian embassy in Indonesia, killing ten.

29. Australia had its first female governor-general at the same time. Dame Quentin Alice Louise Bryce, a former governor of Queensland, served as governor-general from 2008 to 2014.

30. Jack H. Nagel, "Social Choice in a Pluralitarian Democracy: The Politics of Market Liberalization in New Zealand," British Journal of Political Science (1998), Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 223–267. Visible online here.

31. US Navy ships stayed away from New Zealand for the next thirty years. Finally in 2016, an American destroyer, the USS Sampson, was given permission to attend celebrations marking the Royal New Zealand Navy's 75th anniversary.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of the South Pacific

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|