| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 4: Industrial America, Part III

1861 to 1933

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| America's Most Difficult Years | |

Part II

| Reconstruction | |

| The Free State of Van Zandt | |

| The Alaska Purchase, and the Only American Emperor | |

| Grant and the Beginning of the Grand Old Party Era | |

| The Brooks-Baxter War |

Part III

Part IV

| The Spanish-American War | |

| Teddy and the Big Stick | |

| Big Taft and the Bull Moose | |

| Wilson the Reformer | |

| World War I | |

Part V

| The Age of Normalcy Begins | |

| The Roaring Twenties | |

| The Great Depression | |

| The Golden Age of Immigration |

The Panic of 1873, and the Barons of Wall Street

Americans were also distracted from the South by a severe depression in Grant's second term, the Panic of 1873. The cause was the downfall of Jay Cooke and Company, a major banking firm. Previously we saw how Cooke almost singlehandedly financed the Union side of the Civil War by selling bonds for the federal government, and then afterwards he tried to do the same with the Northern Pacific Railroad (see footnote #40), only to find he could not sell several million dollars worth of Northern Pacific bonds. Now overextended, Cooke declared bankruptcy in September 1873; this set off a chain reaction of failures among the businesses Cooke supported, and closed the New York Stock Exchange for ten days. By 1875, 18,000 other businesses had crashed, and the economy did not recover until 1879. The depression was also bad for the Republicans; the 1874 elections saw the Democrats gain control of the House of Representatives, for the first time since 1860. Besides Democrats, the only ones who benefitted were a handful of entrepreneurs who bought out their competitors, now that the stock of so many companies was selling for pennies on the dollar. Thus, it was during this time that multimillionaires like John Pierpont Morgan, Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller got the lucky break they needed to climb to the top of the big-business heap.(46)

The men mentioned above would make more money than anyone had previously seen, becoming modern versions of Midas and Croesus, ancient kings known for their wealth. With that wealth came power. Cornelius Vanderbilt, who led the pack until his death in 1877, made $94 million in just over ten years and once said to an associate, "Law? What do I care about law? Hain't I got the power?" But while earning a profit he also made the railroads more efficient. Previously, passengers and freight had to change trains seventeen times on the 900-mile journey between New York and Chicago. Then after Vanderbilt took over the New York Central Railroad, he overhauled management of the tracks and stations, and cut down travel time from fifty hours to twenty-four. By lowering his rates enough to ruin competitors and help those he had made deals with, and by charging "all that the traffic could bear" where he had no competition, he had his company always paying at least eight percent in dividends on its stock.

It was a similar story with the other men. Today they are often called "robber barons" because not everything they did to make money was legal or ethical. However, they also did more to improve the lives of average Americans than any government program, by streamlining production, eliminating waste, and passing the savings to others in the form of reduced commodity prices on steel, zinc, sugar, etc. And it was Rockefeller, more than anyone else, who turned oil into a profitable business. In the past, petroleum or "rock oil" only attracted attention when it collected in pools on top of the ground. The Indians made war paint out of it, but for most folks it was a nuisance. Sometimes oil came up from salt wells dug into the ground, for example, forcing the abandonment of those wells. In 1807 Abraham Gesner, a Canadian geologist, discovered that kerosene was cleaner and cheaper than the whale and vegetable oils normally used for lamps, and during the next fifty years, methods were found to refine kerosene from crude oil. This created a demand for oil that exceeded the supply, so in 1859 Edwin Drake drilled a well in northwestern Pennsylvania, this time for oil instead of salt; a whole new industry was launched when his first "oil well" succeeded.

Rockefeller saw bigger opportunities in refining oil than in drilling for it, so instead of buying oil wells, he bought into a partnership in a Cleveland refinery. As his company, Standard Oil, acquired other refineries and grew into a major corporation, the price of kerosene dropped from a dollar per gallon to ten cents per gallon, and 300 new products were invented from oil components that had previously been considered waste.

Whereas Cornelius Vanderbilt left 90 percent of his fortune to his favorite son, William Henry Vanderbilt, and gave the rest of his family just enough to keep them from sinking to the middle class, the multimillionaires who came after him felt that accumulating wealth for its own sake was foolish, and they should give something back to society. Carnegie said as much in a book he wrote in 1889, and set the example by giving away more than $350 million, 90 percent of his fortune, in his later years. Most of it went to various libraries, educational, cultural, and peace institutions in North America and Europe, many of which still bear his name; his generosity also inspired folks to name a dinosaur, the saguaro cactus, and towns in Pennsylvania and Oklahoma after him. Rockefeller didn't give as large of a percentage, but he gave more dollars overall; $550 million of his $1 billion fortune went to the charities he set up. J. P. Morgan was a collector of art, rare books and gemstones, and donated much of his sizeable collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In fact, Morgan gave away so much as a philanthropist that whereas he and his partners controlled $1.3 billion at the beginning of the twentieth century, by the time of his death, his fortune had dwindled to $100 million, causing Rockefeller to remark, "Well, well. And to think that Mr. Morgan was not even a wealthy man."

The South Restored, and the Worst Happy Hunting Grounds

Grant's last year as president, 1876, coincided with the nation's centennial anniversary. Americans celebrated with picnics, and by going to a world's fair in the city where it all started--Philadelphia. Like other world's fairs, this one celebrated progress (Alexander Graham Bell's new invention, the telephone, was a popular exhibit here), promoting the idea that life was getting better. Thanks to industrialization, things were changing rapidly. Whereas for most of history the typical person could expect to live very much like his parents did, unless war or some natural disaster got in the way, now there were significant lifestyle changes from one generation to the next. And with the harnessing of electricity, new labor and timesaving devices like the telephone were only beginning to make their impact felt; the light bulb, radio, automobiles, aircraft and countless other inventions would revolutionize the lives of everyone in the late nineteenth-early twentieth century.

But outside Philadelphia, all was not well as the nation's second hundred years began. There was the ongoing depression caused by the Panic of 1873, for a start. And the 1876 presidential election was the most bitterly contested one since 1800. The Republicans nominated Rutherford B. Hayes, a reform-minded governor from Ohio, while the Democrats ran Samuel J. Tilden, a New York governor that had become a hero for putting Boss Tweed in jail.(47) A minor party, the Greenback Party, also ran candidates; its platform called for stopping deflation by printing paper money ("greenbacks") that was backed only by the government's promise to pay, instead of by gold, until there was enough cash for everyone.

When the votes were first counted, it looked like Tilden had beaten Hayes, 51% vs. 47.9%, with 196 electoral votes for Tilden vs. 173 for Hayes. However, the vote was so close in Louisiana, Florida and South Carolina, that both major parties claimed victory, after reports emerged of the Democrats printing misleading ballots and making threats against Republican voters in those states. The editor of The New York Times (then a Republican newspaper), John Reed, refused to accept Tilden's victory, and bribed the Republican-dominated election boards in the three disputed Southern states to take action. In the recount, those officials threw out 14,000 Democratic votes after declaring them improperly cast, and let all Republican votes stand, no matter how questionable they were. When they were done, they declared Hayes the winner in all three states (only 94 Democratic votes had to be removed in Florida). Meanwhile in the West, Oregon went for Hayes by a margin of 500 votes, so that state's Democratic governor fired one of the Republican electors, claiming he was ineligible, and picked a Democrat to take his place. As 1877 began, each of the four states in question sent two sets of electoral votes to Congress. It was the Senate's job to count the votes, and the House's job to pick a president if nobody got a majority, but with Republicans in control of the Senate, and Democrats in control of the House, partisan politics threatened to rear its ugly head there as well. In the end everyone agreed to appoint a 15-member electoral commission to decide the matter, with five members from each house, and five members of the Supreme Court. The party affiliation of the members was eight Republicans, seven Democrats; predictably they voted 8-7 to accept the Republican electoral votes from all four states. Thus, Hayes had an electoral majority of one (185 vs. 184), and became the 19th president.

If you want to claim the Republicans stole the 1876 election, you're probably right. The Democrats called Hayes "His Fraudulency," but let the Republicans get away with it because of an unwritten deal, later called the Compromise of 1877; if the Democrats would accept the final election results, the Republicans would pull all remaining federal troops out of the South. Tilden contested the results for a little while longer, but then gave up two days before Hayes was sworn in, saying, "I can retire to public life with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office." (Did you hear that, Hillary Clinton?) His tombstone shows he believed to the end that he was the real winner, for it says, "I Still Trust in The People."

By giving up the White House for another four years, the Democrats gained the South for nearly a century. The Republicans kept their part of the bargain, removing the last federal garrisons from South Carolina and Louisiana in April 1877. This marked the end of the Reconstruction era. White Democrats quietly took over, and they showed that Reconstruction had been an incomplete revolution by passing laws that segregated the races (the so-called "Jim Crow laws") and made it difficult for blacks to vote. The age of the solid Democratic South now began. For the next eighty years the South was reliably Democratic in nearly every election, while other issues, like industrialization and the settling of the West, kept the attention of most Americans focused elsewhere. During this time the South developed an interesting culture (in literature, music, cuisine, etc.), but in terms of demographics and economics it was behind the rest of the nation; consequently we won't hear much from the South again until the middle of the next chapter.

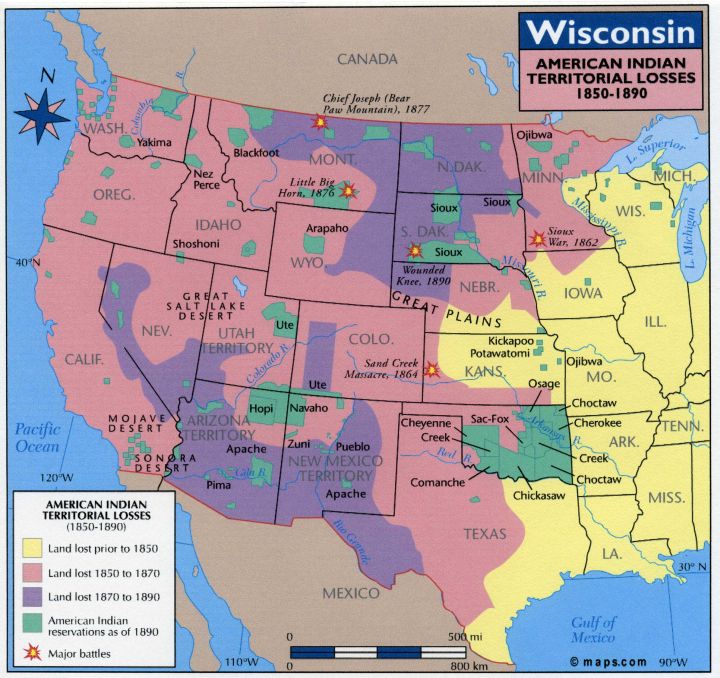

It wasn't only blacks who felt that promises had been broken. In Chapter 2 we saw the Indians driven away from the Atlantic coast; in Chapter 3 the rest of the tribes east of the Mississippi were removed. Then the white man settled the Pacific coast, meaning that the Indians could no longer escape by moving farther west. When the 1860s began, all that they had left was the Great Plains, the northwest basin (modern Idaho, Montana and Wyoming) and the desert southwest, and their rights over all three regions were slipping away fast.

The 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie expired in 1861, and because white settlers were passing through the area, on their way to Denver, they needed protection. At that time, the Colorado mountains were a home for the Ute tribe, and the Cheyenne and Arapaho lived on the plains to the east; indeed, the site of Denver itself had been used as a seasonal campground by the two eastern tribes. In 1861 the federal government signed the Treaty of Fort Wise with the Cheyenne and Arapaho, which promised them a reservation on the banks of the Arkansas River in eastern Colorado. This was only one thirteenth of the land that had been promised to them in the previous treaty, so not all chiefs accepted the new one. The two tribes began making raids to kill isolated settlers, and because most of Colorado's troops were off fighting in the Civil War, the territory was without adequate defenses.

Troops for Colorado became available after the Confederates were driven out of the New Mexico Territory. This led to the Colorado War (1864-65) between the US cavalry, Cheyenne and Arapaho. The bloodiest encounter in that Indian war was the Sand Creek Massacre (November 29, 1864), in which 800 soldiers, led by Colonel John M. Chivington, attacked an Indian camp at dawn; most of the men of the village were away hunting, so nearly 200 old men, women and children were killed. The press initially hailed the battle as a great victory, and called Chivington a hero; only after survivors on the native side were interviewed was it realized that Sandy Creek was really an act of genocide.(48) Though this raised nationwide concern for what might happen to the remaining Indians, by 1867 the army had relocated all tribes in Colorado except the Southern Utes, to reservations in Oklahoma.

Now that the railroads had been built, the rest of the Great Plains became a place worth settling, as opposed to just being a place that settlers needed to pass through. This was encouraged by the Homestead Act of 1862, which said that anyone except former Confederates could have up to 160 acres of free land in the West, if he built a house on it and farmed it for five years. Though the promise of free land is always attractive (and the Great Plains eventually became the best farmland in the world), it turned out to be a tough opportunity. Homesteaders could only take the poorest land, because others, especially the railroads, had claimed the best land already, and the lack of wood meant that houses had to be built out of dried sod, and fires had to be fueled with dung ("buffalo chips"). Still, half a million settlers accepted the offer, turning 80 million acres into farms by 1900.(49)

The Great Plains were ideal for cattle ranching, too. This started in Texas, where cattle had been raised since the days when Spain ruled there. The Civil War and a growing population in the East increased the demand for beef greatly; by the late 1860s, a steer which cost $5 in Texas would sell for as much as $50 in the East. To take advantage of this profit, the ranchers began driving herds of cattle north to Kansas every year, where in cow towns like Abilene and Dodge City the cattle would be loaded on trains and shipped east. To manage the cattle on these journeys, a new type of herdsman appeared, the most famous character of the "Old West"--the cowboy.

Besides free land, the homesteaders needed two more things in order to be successful: protection for their property and water. Besides the threat of Indians, there was the danger of buffalo, and later cattle, marching in and trampling their crops. We'll see in a few paragraphs what was done about the Indians and buffalo. Cattle were a problem because the Great Plains was considered "open range," meaning that the ranchers could let their livestock graze anywhere they wanted. And fights between ranchers and homesteaders weren't the only danger; rival ranchers could compete for the same grazing land, or a "sheep war" could break out between cowboys and sheep herders (sheep and cattle could not graze in the same place because sheep cropped the grass too short to leave any for the cattle, and damaged the soil with their sharper hooves).

In the East, when the issue of private property came up, landowners usually built fences or stone walls to mark the boundaries of their land. That wasn't feasible in the Great Plains, though, because of the severe shortage of both wood and stone. Then in 1874, an Illinois farmer, Joseph F. Glidden, introduced an affordable alternative--the barbed wire fence. Barbed wire caught on so quickly that by 1883, the Glidden factory was producing as much as six hundred miles of barbed wire a day! Widespread use of the barbed-wire fence marked the end of the open range; now livestock could be controlled, crops protected, and water holes preserved.

Water was a problem because if a farm was not lucky enough to be near a river or water hole, the only source for water was deep underground, anywhere from 100 to 500 feet below the surface. Wells could be drilled this deep, but pumping from or lowering buckets to this depth was impossible. Fortunately, the technology to bring water up was available, in the form of windmills, so windmills became a common sight on the plains at the same time as barbed wire. But while windmills could draw enough water for a farmer's family and livestock, they could not provide enough water for irrigation, so most farmers resorted to "dry farming," planting drought-resistant crops and plowing the soil carefully to conserve moisture.

Some settlers still saw mineral wealth as a shortcut to prosperity. Previously we saw gold discoveries bring prospectors and other fortune-seekers to California, British Columbia, and Colorado. The discovery of the Comstock Lode, a major silver deposit, did the same thing for Nevada in 1858. This, along with the Homestead Act, attracted enough settlers to create three new states in just a few years: Nevada (1864), Nebraska (1867) and Colorado (1876).

Rumors circulated for decades about gold in the Black Hills, the home base of the Sioux tribe. These were confirmed in 1874, when General George Armstrong Custer led an expedition of the US 7th Cavalry into the Black Hills and discovered gold there. Of course the Indians were already on this land, and now that settlers coveted the land as well, the government ignored existing treaties that promised the land to the Indians, and tried to relocate the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes to reservations. But after what had happened before, the Indians were dubious about what they would get if they sold or surrendered their property. Red Cloud, a chief of the Sioux, said about such agreements, "The white man made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it."

It was white hunters more than the US Cavalry that subjugated the Indians. The lifestyle of the plains Indians was totally dependent on following the migrating buffalo herds; from the buffalo they got meat, clothing, shelter, fuel and weapons. In the early nineteenth century, the Great Plains were a home where 30 to 40 million buffalo roamed; the Indians gained an advantage when they acquired rifles and horses, but they still did not threaten the herds. White men with rifles and horses, however, were a different matter. They saw buffalo as a crop to be harvested, a cheap way to feed the railroad-building crews. Sometimes they shot the buffalo from trains, thereby avoiding the danger of stampedes. A wholesale slaughter began in the 1860s and continued through the 1870s. At the peak of this "hunt," between 1870 and 1875, two and a half million buffalo were killed every year. Even more irresponsible was the waste involved; some meat and hides were recovered, and some bones were shipped east to be ground into fertilizer, but most of the carcasses were simply left to rot. By 1900, probably only 500 buffalo remained. And with the arrival of farming, most of what remained of the plains ecosystem was obliterated. Now the Indians faced starvation if they did not go to the reservations, where they soon became so dependent on handouts of beef and blankets from the government that they could no longer leave.

We mentioned corruption running wild in the nation at this time; it also affected the government's Indian policy. The officials in charge of the four main reservations (Cheyenne River, Red Cloud, Spotted Tail and Standing Rock) reported having 37,391 Indians, when they really had 11,660. This allowed them to get more funding from Washington; of course they pocketed whatever money they didn't spend on the natives. It also gave officers like Custer a false sense that the plains were almost completely pacified already.

This probably explains the overconfidence the army and the government felt when it came to dealing with the remaining Indians on the loose. In 1876 the army was ordered into southeastern Montana, where the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho were still resisting. The plan was to have three columns converge from Fort Abraham Lincoln (modern Bismarck, ND), Fort Fetterman in Wyoming, and Bozeman in western Montana. Against them the Indians were led by two talented Sioux chiefs, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse.

Brigadier General Alfred Howe Terry led the force from the Dakotas, and Custer's regiment of 655 men formed Terry's advance guard. On June 25 Custer discovered an unusually large Indian village on the banks of the Little Bighorn River. He was supposed to rejoin Terry if he encountered a native force too big to handle, but unaware that the Indians had at least 2,500 warriors, Custer ordered an attack anyway. He and 260 of the men in front were quickly surrounded and killed in less than an hour; the rest of the regiment only escaped because Terry's troops arrived in time to rescue them. This massacre, known both as the battle of the Little Bighorn and Custer's Last Stand, went down as one of the worst defeats in US military history--and it was the last Indian victory in the long struggle against the white man.(50)

The Great Railroad Strike

An industrial revolution may be less violent than a political revolution, but it can still be a painful experience to those workers whose skills are no longer needed. To reduce losses in the aftermath of the Panic of 1873, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad cut wages by ten percent on three occasions, once in 1874 and twice in 1877. On the evening of the third cut, the workers at Martinsburg, WV went on strike, abandoning their trains and refusing to let others operate them; other railroad workers in Maryland and Pennsylvania quickly followed suit. The Sixth Maryland Militia fired on a hostile crowd at the Baltimore railroad station, killing eleven and wounding forty. In Pittsburgh the violence was even worse; 57 strikers, soldiers and rioters were killed, a group of militiamen were forced to take refuge in a railroad roundhouse, and fires destroyed 39 buildings, 104 locomotives and 1,245 railroad cars. Over the next month the strike spread east to Philadelphia, and as far west as Chicago and East St. Louis in Illinois. Mobs in affected cities often supported the strikers; sometimes the police and militia refused to fire on the strikers as well. In Chicago the Workingmen's Party of the United States, the nation's first Marxist-influenced political party, gained control over demonstrations in that city, and a headline in the Chicago Times proclaimed: "Terrors Reign, The Streets of Chicago Given Over to Howling Mobs of Thieves and Cutthroats." President Hayes sent federal troops, and by advancing from one city to another, they managed to put down the strike; forty-five days after it started, it was over.

Theoretically the workers were the losers (one complained, "We were shot back to work"), but by paralyzing the economy across much of the nation, they realized they would have considerable power if they were united; they were proud of this and the fact that there had been few desertions and few scab laborers to interfere with the strike. For that reason, 1877 can be seen as the birth year for the American labor movement. The Noble Order of the Knights of Labor, a labor union founded a few years earlier, grew exponentially after the strike, peaking with 700,000 members in the mid-1880s. In 1881 Samuel Gompers organized a quarter million craftsmen to form the Federation of Trades and Labor Unions, which later was renamed the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Less political than the Knights of Labor, Gompers called for "pure and simple unionism," putting the primary emphasis on higher wages, shorter hours and better working conditions.

Many observers blamed the strike, and labor activities in general, on foreign political ideas; there were some anarchists, socialists and communists in the movement, though they never succeeded in taking over it completely. Some businesses tried to curtail the influence of the unions by hiring more immigrants, who were less likely to complain about how they were treated. As early as 1870, for example, a Massachusetts shoe manufacturer named Calvin Sampson fired his unionized workers and brought in 75 Chinese immigrants from the west coast to replace them; by paying each Chinese worker $26 a month, he was able to save $840 a week. This led to an anti-immigrant backlash. In 1882 then-president Chester A. Arthur vetoed a bill that would have blocked the immigration and naturalization of Chinese for ten years, but Congress passed it anyway. However, nobody could stop the endless supply of new workers coming in from Europe.

The Spoils System Kills the President

For the 1880 presidential election, the leader of the Republicans' Stalwart faction, New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, proposed bringing back Grant. No president had ever run for a third term before, and there was considerable nervousness about doing it now, so the other factions wouldn't have it; they went with Blaine, the leader of the Half-Breed faction.(51) This deadlocked the convention, so after thirty-six ballots, the Republicans settled on a dark horse from Ohio, a freshman senator named James A. Garfield, with a Stalwart, Chester A. Arthur, as his running mate. As for the Democrats, they went with a Civil War hero, General Winfield Scott Hancock. This election was fairly quiet, with tariffs being the only significant issue (Republicans were for higher tariffs, while Democrats were against them). The popular vote was very close; out of nearly nine million votes cast, Garfield was ahead by only 9,464. He got a solid electoral majority, though, because while Hancock swept the South completely, Garfield got most of the North and West, for a 214-155 lead.

As president, Garfield showed he was with the Half-Breeds by choosing Blaine as his Secretary of State. Then, as part of his house-cleaning program, he picked a rival of Senator Conkling to head the New York Customs house, prompting Conkling to resign when he lost the showdown that followed. Otherwise, he never got the chance to do much; he was killed by the "Spoils System" first. On July 2, 1881, not quite four months after being sworn in as president, he and Blaine were in a Washington train station, preparing for a trip to New England. Waiting for them in the station was Charles J. Guiteau, a job-seeker who had been hanging around Washington for months, hoping to become the minister to Austria or France. Guiteau was a religious fanatic from the Oneida colony in New York, with no useful professional or social skills except an annoying persistence. When Blaine personally rejected his requests for employment, Guiteau decided it was for political reasons, and that Garfield was ultimately responsible, so on this day he shot the president twice from behind and announced, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts . . . Arthur is President now!!" before giving himself up to the authorities.

One bullet lodged in Garfield's spine and could not be found. For the next eighty days, he suffered from fevers and pain, while the doctors worked hard to finish him off, in what is now considered one of the worst examples of medical quackery in history. The wounded president was moved to a seaside house in New Jersey, where it was thought the fresh air would do him good, but instead he died on September 19, and Vice-President Arthur moved into the White House.(52)

Because Chester Arthur got to the top through wealth and connections with the right people, not much was expected of him when he became president. Instead, he was both honest and efficient, doing well enough that some must have wondered why Garfield, and not Arthur, had been the number one man on the 1880 ticket. He acted independently of all Republican factions and though Congress was almost evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats, he solved the patronage problem and got rid of the spoils system by supporting the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. This legislation created the Civil Service Commission, which would henceforth give exams for those seeking federal office, and grade candidates on ability, rather than on political loyalty. He also prosecuted post office officials who had conspired with stagecoach operators to steal millions of dollars, vetoed a river-and-harbor spending bill that he considered excessive, persuaded Congress to fund the building of a new steel navy, and acquired Pearl Harbor in Hawaii as a naval base.

Arthur accomplished all this because he succeeded in concealing another secret; he was suffering from Bright's disease, an incurable kidney ailment. America had just lost one president, and if the public had known that this one might not live long either, they would not have allowed him to govern effectively, treating him as a "lame duck" instead. Arthur was accustomed to an elegant lifestyle, so under him life in the White House was a near-constant party; he rose late in the morning, took two to three hours for dinner, and acted like nothing was wrong. Because the disease was made worse by high blood pressure, the danger to Arthur increased when he was active, but when it came time to pick a Republican presidential candidate for 1884, Arthur even made a half-hearted attempt to run for a second term. The laughter and song of Arthur's presidency worked; he beat the odds and completed his term, finally dying in November 1886, sixteen months after leaving the White House.

Grover the Good

James G. Blaine was a great orator who had been with the Republican Party since it was founded, and ran unsuccessfully for president in 1876 and 1880, so for the 1884 presidential election he was the GOP's first choice. But while his supporters called him the "plumed knight," and the greatest Republican of all, he was also a slippery liar who had used his position as a Maine senator to take stock from the corporations whose interests he defended in Congress. A congressional investigation of Blaine's activities produced some incriminating letters, which Blaine tried to steal. Caught in the act, Blaine had to read each of the letters he had stolen on the floor of the House, after which he explained each one in a way favorable to his reputation. This made it look like he hadn't really done anything wrong, but the embarrassment of that scandal kept him from getting nominated until 1884, when most Americans had forgotten the affair. Democrats made fun of Blaine with this rhyme:

"Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine,

The continental liar from the state of Maine!"

Many Republicans refused to support a candidate as tarnished as Blaine, and went with the Democratic candidate instead, Stephen Grover Cleveland. Loyal Republicans called these defectors "mugwumps," claiming it was an Algonquin Indian word meaning "great captain" or "war leader," but the usual interpretation was that a mugwump was somebody sitting on the political fence, with his mug on one side and his wump on the other!

Among the Democrats, Cleveland rose like a rocket because as one newspaper put it: "1. He is honest. 2. He is honest. 3. He is honest." Starting out as a lawyer and sheriff in New York's Erie County, he was elected mayor of Buffalo in 1881, and governor of New York in 1882. Tammany Hall hated him because to them he was the worst kind of politician--a politician that can't be bought--and the voters loved him for the same reason. Soon Democrats were calling him "Grover the Good."

Grover Cleveland.

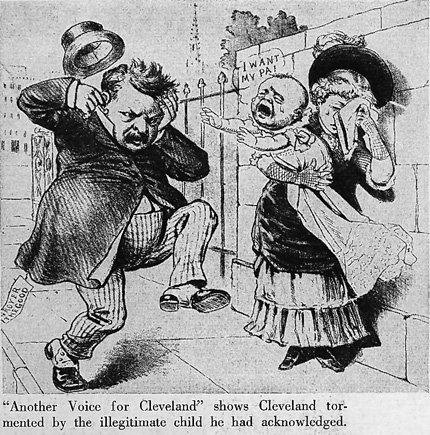

The contrast between Cleveland and Blaine resulted in the 1884 election being the dirtiest of the nineteenth century. In July a Buffalo newspaper exploded a bombshell by reporting that in the 1870s, Cleveland had fathered an illegitimate child, gave financial support to the mother and child for a while, and that eventually the child went to an orphanage and the mother, now an alcoholic, ended up in an asylum. Since this was in the middle of the Victorian era, such allegations could have destroyed the career, marriage and reputation of any man. Delighted Republicans taunted Democrats by saying, "Ma, Ma, where's my Pa?"

Cleveland instructed his staff, "Whatever you say, tell the truth." Accordingly, they pointed out that Cleveland did acknowledge the child as his own, but the woman in question had affairs with several men, and nobody could prove which one was really the father. Cleveland took responsibility because he was a bachelor, and didn't want this "illicit connection" to ruin anyone else. He had done the best thing one could do to fix a bad situation. This confession made Cleveland look even better than before, when voters compared it with what Blaine must be hiding.

In every election back then, the Democrats started at a disadvantage, so after all this, Cleveland was still barely ahead of Blaine in the polls. It was so close that a bad incident involving Blaine decided this election. One week before Election Day, a committee of New York City ministers came to Blaine, to assure him they were not mugwumps. Their spokesman was a Presbyterian named Dr. Samuel Burchard, and he said, "We are Republicans, and don't propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with the party whose antecedents have been rum, Romanism and rebellion." Later that evening Blaine went to a banquet with several unpopular rich men, including Jay Gould and William Henry Vanderbilt (Vanderbilt had offended the nation two years earlier by shouting "The public be damned!", when asked if he had introduced a new fast train to benefit the public). Irish voters, who were mostly Catholic ("Romanists") and didn't think rum was bad, abandoned Blaine for Cleveland. This caused New York to go Democratic, giving Cleveland enough electoral votes to win. Triumphant Democrats added a new line to the naughty Republican slogan:

"Ma, Ma, where's my Pa?

Gone to the White House! Ha! Ha! Ha!"(53)

"Public office is a public trust" was a Democratic slogan in the 1880s, and Cleveland followed it so well that he sometimes acted as if the two major parties didn't exist. In that sense, you could call him Washingtonian (one author called him "America's Libertarian president"). The issue of patronage came up, for example, because after a generation of Republican rule in Washington, most federal jobs were filled by Republicans; many of them got those jobs because of politics, whether they were competent or not. Whenever a Republican stepped down, Cleveland appointed a Democrat to replace him, which angered Republicans, but he also offended Democrats and independents by not firing Republicans wholesale, nor did he do much to expand the civil service program that Chester Arthur had started. However, he did check the qualifications of each Democrat whose appointment was suggested to him, and refused to accept them if they were unqualified or had a criminal record; this allowed him to keep his reputation for honesty.

Much of Cleveland's first term was spent vetoing routine bills that were popular but expensive. This was especially the case with Civil War pension bills, which had gotten out of hand, twenty years after the war ended. Originally the pensions had only been meant for soldiers who were too badly wounded to work, but now pensions were being given to all 1860s-era veterans, their widows and even their parents. In the end Cleveland vetoed more than a hundred fraudulent spending bills. Likewise, when Texas suffered a drought in 1887, Cleveland vetoed a bill to buy $10,000 worth of seed for the farmers because he could not find anything in the Constitution that authorized spending public money to help those who had fallen on hard times, when the charity of ordinary citizens was available. Compare that with the response to Hurricane Katrina in our own time; can anyone imagine today's government refusing to come to the rescue when a natural disaster strikes? Because Cleveland's spending cuts resulted in a massive budget surplus, he also wanted to cut tariffs. Unfortunately he couldn't get Congress to agree on anything but a minor reduction, so when his first term ended there was $97 million in the treasury.(54)

If Cleveland came across as irritable, it was because he was also lonely. In the summer of 1885 he proposed to Frances Folsom, the daughter of his former law partner. This was controversial because she was 21 and he was 49, and some spread a rumor that Cleveland was really going to marry her mother, causing him to remark, "I don't see why the papers keep marrying me to old ladies all the while." The wedding took place the following June, making Cleveland the first president to get married in the White House. Afterwards, like today's paparazzi, the press ruined the honeymoon by surrounding the country cabin in Maryland where the president and his bride stayed, and watched them constantly with cameras and telescopes. Cleveland hated the media after that.(55)

Meanwhile in the cities, labor boiled over again. This time an eight-hour work day was what workers wanted the most, and on May 1, 1886, 340,000 union members staged a nationwide eight-hour strike to make their point. In the days that followed, the Chicago police and the Wisconsin National Guard (in Milwaukee) fired on crowds of "eight-hour" protesters. This prompted a meeting of 3,000 union members at Chicago's Haymarket Square on May 4 to protest the shootings. It started out peacefully enough; the mayor of Chicago came by to listen, and went home early when it looked like nothing was going to happen. The crowd included anarchists and socialists, though, and after the mayor left, the speeches grew more fiery, now calling for violent revolution. The police tried to disperse the crowd, when suddenly, someone threw a bomb in the midst of them, killing eight and wounding sixty-seven. The cops fired back, killing four and wounding an unknown number of workers.

This was the first time dynamite had been used as a weapon in the United States, and the Haymarket Riot shocked the whole nation. Eight anarchist agitators at the demonstration were arrested and charged with murder. Because it was never discovered who actually built or threw the bomb, the trial of the Haymarket eight is now seen as one of the worst miscarriages of justice in US history. The prosecution at the trial reasoned that even if none of the defendants was guilty of throwing the bomb, they incited whoever did and should receive the same sentence. All eight were found guilty; one was sentenced to fifteen years in prison while the rest got death sentences. The governor commuted two of those sentences to life in prison, one blew himself up with a smuggled dynamite cap the day before his execution, and the remaining four were hanged.

A wave of anti-labor hysteria came in the aftermath of the Haymarket bombing. Newspapers and magazines spread the idea that if you favored the goals of the labor movement, like the eight-hour day, you were also in favor of foreign thugs, anarchy, Marxism, dynamite and free love. The Knights of Labor declined rapidly, though the current KoL leader, Terence Powderly, had not supported the strike or demonstrations. An eight-hour work day would not become a reality until the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938. Abroad, socialists declared May Day a workers' holiday in commemoration of the 1886 American demonstrations.(56)

In the 1888 presidential election, the tariff issue came up again; Republicans still wanted higher tariffs to protect American jobs, while Democrats thought lower tariffs and free trade would be better for the consumer. New York and Indiana were expected to be the swing states, and because New York was Cleveland's home state, the Republicans picked Indiana Senator Benjamin Harrison as their candidate. Harrison had a good name, as the grandson of former president William Henry Harrison (the 1840 campaign song "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too" was brought back and changed to "Tippecanoe and Morton Too," to include Harrison's running mate, Levi Morton), and he was a Civil War hero, ending the war as a brevet brigadier general. Unfortunately, he was also extremely uncharismatic; in Star-Spangled Men, a book about the ten worst US presidents, Nathan Miller wrote that Harrison "looked like a medieval gnome and had a handshake like a wilted petunia."

Benjamin Harrison.

Harrison stayed home in Indianapolis and let big businesses like the American Iron & Steel Association campaign for him. There were also reports of massive Republican vote-buying, with the Republican national committee treasurer giving these instructions to agents in Indiana: "Divide the floaters [voters willing to sell their votes] into blocks of five and put a trusted man in charge of these five, with the necessary funds, and make him responsible that none get away, and all vote our ticket." Still, in the end a Republican trick put the GOP over the top. A California Republican named George Osgoodsby wrote a letter to the British minister, Sir Lionel Sackville-West, in which he pretended to be Charles J. Murchison, a former British citizen. "Murchison" asked which candidate he should vote for, because he wanted to support whoever would be best for Britain, and Sackville-West, a remarkably dim-witted ambassador, wrote back that he thought Cleveland was the best man. Osgoodsby then published the letter; the Irish-American voters who voted for Cleveland last time didn't want anything to do with a pro-British candidate, and switched their votes to Harrison. When the votes were counted, the results were much like they had been in 1876; Cleveland was ahead in the popular vote by nearly 100,000, but because New York had gone for Harrison, the Republicans had a 233-168 majority in the Electoral College, so Harrison won.

The 1888 elections also gave a Republican majority to both houses of Congress, and it was easy for them to solve Cleveland's $97 million budget surplus "problem." They simply voted to give monthly pensions to half a million Civil War veterans, something Cleveland would have opposed, and that eliminated the surplus in three years. Next, because the Republicans were now the party of big business, they raised the tariff to its highest rate yet.(57) This caused prices on all manner of goods to shoot up, ending the deflation that had marked most of the post-Civil War era. Finally, the Harrison administration approved vast expenditures for the construction of public buildings and the improvement of rivers and harbors. For foreign policy, Harrison brought back James G. Blaine as Secretary of State, and he improved relations with Latin America by setting up the first Pan-American Conference, a forerunner to the Organization of American States.

These activities and others meant that the 51st Congress became the first to spend a billion dollars in peacetime. With today's national budgets in the trillions, a billion dollars seems rather trivial, but in 1890 it was enough to make someone accuse the Speaker of the House, Thomas Brackett Reed, of presiding over a "Billion Dollar Congress." Reed came back with, "Yes, but this is a Billion Dollar Country!"(58)

Reed's remark about a billion dollar country might have been the perfect ad-lib, but the math was way off. In 1890 the entire national wealth, in real estate, railroads, mines and factories, was estimated at just over $65 billion. The Gross National Product for that year was $12.3 billion, which when divided among a population of 63.1 million, worked out to a per capita income of $195. Unfortunately the nation's wealth was also very unevenly distributed, and the problem was going to get worse before it got better.

It was going to get worse because big business had gotten even bigger. Because the government would not allow any corporation to become a monopoly in its field of expertise, the heads of corporations decided to cooperate, instead of trying to drive each other out of business. One way of gaining absolute control over a field was to have several companies trade stock and set up a board of overseers, to regulate prices and otherwise direct their activities. Nowadays we might call such an organization a cartel; back then they were known as "trusts," because the overseers were called "trustees." The first successful trust was the Standard Oil Trust, organized in 1882 by John D. Rockefeller and eight other trustees. By the end of the 1880s, almost every American industry was controlled by a trust: there was a copper trust, a sugar trust, a steel trust, a flour trust, a tobacco trust, etc. In Congress the Senate became a millionaire's club, with individual senators representing the interests of one trust or another, and a Wall Street banker as the presiding officer.

As early as 1884, a third party called the Anti-Monopoly Party appeared, to express opposition to the new kind of monopoly. In the 1888 election, both the Democratic and Republican Party platforms declared themselves against the growth of trusts, and twenty-five states passed laws regulating trusts by 1890. This prompted Congress to pass its own law in 1890, the Sherman Antitrust Act. The law was named after a famous senator, John Sherman of Ohio, but he was an unwitting sponsor who did not understand the final version of the law; one colleague suggested that he never even read it. After that, the Republicans chose not to enforce the law; Presidents Harrison, Cleveland and McKinley paid little attention to it; soon court action hindered its enforcement, making it toothless. In 1895 the Supreme Court almost killed the Sherman Antitrust Act altogether by ruling that the American Sugar Refining Company, which controlled more than 95 percent of the nation's sugar production, was not a monopoly. Not until after the twentieth century began would there be major economic reform. By that time, you could claim that men like Carnegie, Rockefeller and Morgan were the real owners of the country.(59)

"I Will Fight No More Forever"

The Harrison administration also saw the conclusion of the Indian wars. One year after the battle of the Little Big Horn, the Nez Perce were the only major tribe that still resisted US authority in the northwest. When white ranchers decided they wanted the land in northeast Oregon for their cattle, the US government ordered the Nez Perce to move to a reservation established for them in an 1863 treaty, and sent in the 7th Cavalry, under General Oliver Howard, to forcibly remove those who would not go. One band of 750 Nez Perce, instead of complying, marched east through Idaho and northwest Wyoming, and then turned north into Montana. Their goal was to escape into Canada, or at least join with Montana's Crow tribe. Instead, 2,000 cavalrymen pursued them. There were thirteen engagements along the path the Nez Perce took, which the Nez Perce usually won. However, their luck ran out in the Bear Paw Mountains, just 40 miles short of the Canadian border, where the cavalry surrounded them and forced their surrender, after a five-day battle in freezing conditions (October 5, 1877). The principal chief at this point, Chief Joseph, gained admirers for his skill in leading the tribe during its retreat, and a reputation as a peacemaker for the eloquent speech he made when he surrendered:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking-Glass is dead, Ta-Hool-Hool-Shute is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men [Chief Joseph's brother] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are--perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever."

In 1873 and 1879, most of the land belonging to the Utes in Colorado and Utah was taken away, after gold was discovered on it, leaving the Ute tribe with only the reservations they have now. Southwest of them, the Apache had always been on bad terms with everybody else, and because they had fought other Indians, Spaniards and Mexicans in the past, it was natural for them to resist US expansion into their territory as well. From 1862 until his death in 1874, a chief named Cochise led the Apache in an on-and-off guerrilla war, with the intention of driving all white men out of the southwestern desert. Although he did not succeed in doing this, the population of New Mexico and Arizona was greatly reduced during the 1860s. The other famous Apache at this time, Geronimo, was not a chief but strictly a military leader; he led a series of raids upon both Mexicans and Anglo-Americans, from 1858 to 1886. At one point he had 5,000 US troops, one fourth of the available army, in pursuit of him. When he surrendered for the last time and was sent as a prisoner to Florida, he was leading a band of men, women and children that had shrunk to thirty-eight members.

The last act in the Indian wars began with a peace movement. On the first day of 1889, a holy man from the Paiute tribe in Nevada, known by the native name of Wovoka and the English name of Jack Wilson, saw an eclipse of the sun--and had a prophetic vision. In this vision, Wovoka saw himself standing before God in Heaven, with his dead ancestors nearby, busy doing their favorite activities. He came from this convinced that God wanted the Paiute to live a righteous life, so they could be reunited with their relatives in the other world. After that, Wovoka/Jack preached that if every Indian took part in a traditional five-day dance, called the Ghost Dance, and learned to live in peace with the white man, the dead would come back to life, the buffalo would return to the Great Plains, and all evil in the world would disappear.

The Ghost Dance was not popular with the Navajo, who are dreadfully afraid of anything having to do with death, like cemeteries. Other tribes in the West, though, received the Ghost Dance message favorably, and even the Mormons in Utah investigated it. Indeed, if Wovoka/Jack had lived a few decades later, he probably would have been a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize. Unfortunately for him, others interpreted it differently. One tribe, the Lakota Sioux, thought the prophecy meant that all white men would be driven off their lands, and they started wearing "ghost shirts" with magic symbols (pictures of stars and birds), to make themselves immune to bullets. And the federal government saw the Ghost Dance as a subversive movement, mainly because of the Lakota response. Troops were sent to the Sioux reservations, where tensions were already high because the government had recently cut food rations in half. On December 15, 1890, they tried to arrest the most famous Lakota chief, Sitting Bull, for failing to stop his people from performing the Ghost Dance; 150 Indians showed up to prevent the arrest, shots were fired, and fourteen were killed in the resulting gunfight, including Sitting Bull himself. Two weeks later, at Wounded Knee Creek, the 7th Cavalry surrounded two migrating tribes of Ghost Dancers with the intention of disarming and relocating them; again fighting broke out, and by the time it was over, twenty-five cavalrymen and at least 150 Indians were dead; an unknown number of Indians who fled the battle soon died from exposure to the winter weather. Obviously the ghost shirts did not work.

That last battle is known as the Wounded Knee Massacre. There would be no more resistance from the Indians after this, now that they saw it was futile to do so. Although some Indians have survived to this day (mostly on the reservations), their active role in American history was over.

How the West was lost.

The Great Barbecue

The settling and development of the West was not complete until all the territories became states, but by the time of Wounded Knee the end was in sight. Six new states were created during Benjamin Harrison's presidency, more than under any other president. Those six were Washington, Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota in 1889, and Idaho and Wyoming in 1890. Previously it was possible to draw a "frontier line" across a map of the nation, showing which areas had been settled, but after the 1890 census this could no longer be done because too many people lived in every western state and territory, so the government declared the frontier closed.

Utah had been ready for statehood since the 1850s, but Congress had rejected every petition because it didn't want anything to do with the Mormon practice of polygamy. That logjam was broken in 1890 when the LDS Church issued a manifesto abolishing polygamy. During Utah's long period as a territory, two political parties arose there, the People's Party for the Mormons and the Liberal Party for the "Gentiles," but once it looked like Utah was going to become a state, those parties dissolved and their former members organized local Democratic and Republican chapters. Statehood finally came in 1896.

Oklahoma was a special case; until now the federal government had used it as a dumping ground for unwanted Indians. It had been called the Indian Territory since 1834, meaning that white settlers were not allowed there. Whites still wanted to move in, though, and as lands elsewhere were filled up with homesteads, the pressure to let in the whites increased. From 1879 onward, homesteaders sneaked in from Texas and Kansas, and were routinely rounded up and deported by US army patrols. Finally the federal government agreed to open up 2 million acres of unoccupied land for these folks, calling it the Oklahoma Territory, and on April 22, 1889, 50,000 settlers lined up on the border, waiting for the signal that they could go in legally.(60) When that signal came, everyone rushed to claim a tract of land; by evening, virtually every lot in the zone had been taken, and now tents, wagon boxes, dugouts and crude cabins marked the first homes of the newcomers. In 1890 a strip of land just above the Texas Panhandle was added to the area open for settlement. Because the Indians were now in the minority, the rest of the Indian Territory was merged with the Oklahoma Territory in 1907, to create the state of Oklahoma.

That left New Mexico and Arizona as the last territories in the American West. When both of them became states in 1912, the continental United States assumed the organization it has held ever since.

The second half of the nineteenth century is seen as the time of the "Old West," glorified in countless movies, books and TV shows. In addition to the cowboys and Indians, this era is associated with no-nonsense sheriffs, gunslinging outlaws like Billy the Kid and Jesse James, the gunfight at the OK Corral, and "boom towns" where saloons were the main meeting place. While much of this was true, a lot of it was also exaggerated to make a good story, just like the "tall tales" about heroes like Paul Bunyan. For example, one of the outlaws, Charles Bolles, was notorious as Black Bart, the stagecoach robber who would leave samples of poetry with his victims. When the authorities finally caught him, it turned out that he showed up on foot to rob stagecoaches because he was afraid of horses, and the shotgun he carried was never loaded!

Click here to see an ad for another feature of the Old West, Buffalo Bill's Wild West show (283 KB, will open in a separate window).

Life in the cow towns, and mining communities like Virginia City, NV, was indeed rough for a time. Anyone with money, like cowboys who had just been paid for delivering cattle to the cow towns, were tempted to spend it on drinking and gambling, and there were plenty of unscrupulous folks around to help separate them from their cash. As in frontier settlements elsewhere, these were lawless places, often controlled by gangs, where fights were commonplace. And because violent deaths were commonplace as well, burials in cemeteries like Boot Hill (in Tombstone, AZ) were simple, with epitaphs that said little besides the name of the deceased and what killed him, like:

"Here lies

Lester Moore,

Four slugs

From a 44,

No Les,

No More."

The Old West was rough because of a shortage of police and soldiers to maintain law and order.(61) That changed, though, as more and more people moved in and a local infrastructure developed. By 1900, the typical Western community was nearly as civilized as the typical Eastern one.

Before we continue the narrative, it would also be useful to point out that cowboys weren't really "knights of the western plains." The image most of us have from Western stories is that the typical cowboy was a tall, bandit-chasing white man who is also an expert marksman. Cowboys could also be blacks, Mexicans, or American Indians, and they weren't likely to be of more than medium height, because the horse had to carry him around, after all! And he had good reason to carry a gun, because of the lack of law enforcers mentioned above; cowboys would band together for mutual protection, when necessary. Finally, cowboys were more likely to be moving, breeding, branding and rounding up cattle, than patrolling like a policeman, looking for the bad guys.

Today the cowboy is a popular symbol of conservatism, thanks to a lifestyle that depended on rugged individualism, and their portrayal in movies by actors like John Wayne (see above) and Ronald Reagan. In its glory days, however, the West produced some political ideas that the rest of the nation considered radical. Two of them were ballot initiatives, which let the voters make some decisions that were normally made by state legislatures, and special recall elections to remove unpopular/incompetent officials. In 1869, Wyoming became the first place in the United States to grant women the right to vote. The early 1890s also saw a political party appear that represented Western interests, the US People's Party, better known as the Populists.

The plight of the Great Plains farmers, and that fact that neither Democrats or Republicans were doing anything about it, was what launched the Populists. Nothing the farmers did seemed able to bring them a profit. If they had a good harvest, prices dropped like a stone at the market; if they were hit by a drought or locusts, the land didn't produce enough to pay the bills, either. As thousands of homesteaders from the past generation sold their land or just quit farming, others joined with the Knights of Labor to launch an agrarian revolt.

While experts in the East thought the farmers were losing money because they had produced too much food, activists for the farmers, like Mary Lease ("Raise less corn and more hell"), thought the root cause was too much wealth being drawn into the hands of monopolists, railroads, and tax collectors. The Populist answer to this was a wealth-redistribution program that may not have been socialism, but sounded a lot like it. Their party platform called for a graduated income tax, direct election of senators by the people (instead of by state governments), government ownership of railroads, telegraph and telephone companies, a return to the government of excess land owned by railroads and corporations, banks in post offices to compete with private banks, and the widespread coinage of silver, to make money more widely available than it was under the gold standard.

The 1890 congressional elections ended the reign of "Czar Reed" and the Republican majority, and many of the newcomers had Populist leanings; nine representatives and four senators were card-carrying members of the Populist Party. For the 1892 presidential election, the Republicans and Democrats ran the same candidates they ran in 1888 (Harrison and Cleveland), while the Populists nominated James B. Weaver, an Iowa congressman who had once been a Greenbacker. Weaver was one of the most successful third party candidates in American history; getting 8.5% of the popular vote, winning four states and receiving electoral votes from two more. However, independent and third party candidates tend to draw votes away from the incumbent party, and that happened here; Harrison was defeated and Cleveland returned to the presidency. We saw in Cleveland's first term that he was a firm believer in smaller government, so ironically, the Populist revolt gave them a president who was against everything they stood for.(62) After 1892 the Populists faded away, as their ideas were adopted first by the Democrats, and later by "progressives" from both major parties.

The Gay Nineties

As the end of the nineteenth century approached, most Americans had reason to feel good about the future; unless you were an American Indian, Southern black or Western farmer, life was definitely getting better. This was the height of what the French called La Belle Epoche, the "beautiful time," because the only wars were fought overseas, against unruly natives who didn't want to become subjects of some colonial empire. Besides peace, the Western nations were experiencing unprecedented social, scientific and material progress.(63)

To celebrate this progress, another world's fair was held, this time in Chicago in 1893. Called the Columbian Exposition, it was supposed to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America by Columbus, but it was really a celebration of American culture, just as the Great Exhibition of 1851 had been a celebration of British culture. It also celebrated the rebuilding of Chicago, because much of it had burned down in a city-wide fire in 1871. Forty-six nations participated, and 26 million visitors came during the six months it was open. This became the meeting place for the first Parliament of World Religions, an important early step toward the ecumenical movements of today (the second Parliament of World Religions wasn't held until a full century later, in 1993). The Ferris wheel was invented for the exhibition, and likewise it would be a century before a larger Ferris wheel was built anywhere. William "Buffalo Bill" Cody's Wild West show made an appearance next to the fair, though not within its gates. Most of the fair's exhibits were in a group of white stuccoed buildings around the central courtyard called the "White City"; they were only meant to be temporary, and sure enough, were destroyed by arson during the Pullman Strike of 1894. But the most popular exhibit may have been a person, not a building or invention; a belly dancer who went by the name of Little Egypt introduced the hootchy-kootchy to the American public, and the whole nation heard about her the day after the fair opened.

Unfortunately, the Columbian Exhibition and the beginning of Grover Cleveland's second term coincided with yet another economic depression, the Panic of 1893. This panic started when India stopped coining silver, leaving the United States as the only nation that backed its currency with both gold and silver. As with the Panic of 1873, hundreds of banks across the nation shut their doors, leaving the economy in a mess. Unemployment climbed above ten percent, and remained in double-digit figures for the next five years (see J. P. Morgan's response in footnote #59).

Republicans blamed the depression on the fact that a Democrat had been elected President, destroying people's confidence in the economy, while Cleveland blamed it on the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, an 1890 law that increased the amount of silver the government would buy every year. He ordered Congress to repeal the Act, and while the House quickly complied, the Senate balked; Western Democrats, like the Populists, thought the solution was to coin more silver, not less. They had a good point, because there was now less money in circulation than there had been in 1865; no wonder the farmers were having a hard time getting a fair price for their crops. The Populist solution to the cash shortage, called "free silver," was to have the Treasury buy as much silver as it could afford, and fix its value at 1/16 the price of gold. This would cause inflation, but free-silver advocates did not see inflation as a bad thing, because it would reduce the value of existing debts. When those favoring the repeal made the accusation that producing more silver was a scheme to help Western mines, a pro-silver Nebraska congressman, William Jennings Bryan, agreed: "Is it any more important that you should keep a mercantile house from failing than that you should keep a mine from suspending?" In other words, this was a battle between the producers of the West and the manufacturers, merchants and administrators of the East. Bryan had brought back the old rivalry between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, the farmer vs. the capitalist.

When Democrats and Republicans joined together to launch a filibuster against the repeal, Cleveland declared that when filling government jobs, he would accept no recommendations from any senator that opposed the repeal. Because patronage was still considered important, this was the president's most powerful weapon. Enough Democratic senators knuckled under to pass the repeal; those that didn't lost much of their power and influence.

In the middle of the silver debate, Cleveland learned that he had cancer of the jaw. As soon as Congress adjourned for summer vacation, he sneaked on board a yacht in New York City's East River, to have the tumor operated on. The crew of the yacht was told he came to have two teeth pulled; the real reason for his visit was hidden to keep the press away, and to give the president time to heal up and return to the debate when Congress reconvened. It took two operations; the first removed part of the roof of his mouth, and the second put in a vulcanized rubber prosthesis. The doctors did all their work while the yacht was at sea, so it's a good thing the ocean was calm! Two months later, one of the doctors broke the secrecy, because it was clear by then that Cleveland was going to be all right, and a story about the surgery appeared in the Philadelphia Public Ledger. However, other doctors ridiculed the report, saying the president never looked better. It wasn't until 1917, twenty-four years after the operation and nine years after Cleveland's death, that his secret visit to the yacht became common knowledge, when another surgeon who had been on the yacht told everything to the Saturday Evening Post.

Next, Cleveland returned to an issue from his first term, lowering the tariff. Again, the House approved the measure, but the Senate refused to do it without a fight. And because Cleveland spent most of the good will he had with Congress on repealing the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, he had less leverage this time. Over a two-month period, senators amended the bill so that the new lower tariff did not apply to any product whose interest was represented by somebody in the Senate. Cleveland reluctantly allowed the final version of the bill to pass, because it still called for a tariff lower than the McKinley one, though not by much.(64)

Outside of Washington, the depression was made worse by the latest labor unrest, the Pullman Strike. The Pullman Palace Car Company had a reputation for building the best railroad cars in the nation; the company president, George Pullman, had invented the sleeping car in the 1860s. To keep his workers happy, Pullman paid them well and built an attractive company town for them in Illinois, where the homes had complete indoor plumbing and gas (luxuries by the standards of the day), free schooling up to eighth grade for the employees' children, and a free public library. However, Pullman also ruled over the town like a benevolent dictator. Money owed to the company stores was automatically deducted from worker's paychecks, so a worker who spent too much could find himself with no take-home pay. Independent newspapers, public speeches, town meetings and private charities were prohibited. Inspectors routinely visited homes to make sure they were clean, and while there was a church, it was empty because Pullman only gave certain denominations permission to use it, and none of them were willing to pay the rent he charged. As one worker put it, "We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shop, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman church, and when we die we shall be buried in the Pullman cemetery and go to the Pullman Hell."

When the Panic of 1893 hit, demand for train service dropped and the Pullman company cut its high wages to offset the losses. Unfortunately the company town did not cut its high rent, water or gas bills to match the wage cuts. When a committee delivered Pullman a petition to restore their wages, he refused to compromise on anything, and fired three of them. The remaining workers responded by going on strike in May 1894, and the American Railway Union joined the strikers by ordering a boycott of all trains that had Pullman cars. This paralyzed all railroad traffic around Chicago. The strike was peaceful at first, until a mob attacked a train carrying mail; and President Cleveland responded by sending the army into Chicago to break the strike. Thirteen strikers were killed in the violence that followed, but the strike was over. Both the mayor of Chicago and the governor of Illinois protested the use of federal troops, and told Cleveland to take them back, but Cleveland showed his determination by saying, "If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postal card in Chicago, that card will be delivered." Afterwards, a national commission studying the causes of the strike declared Pullman's company town "un-American," and it was annexed by Chicago in 1898. Pullman himself died in 1897, and because he was disliked by so many people, he was buried at night in a lead-lined coffin, surrounded by a steel-and-concrete vault, with cement poured in to keep labor activists from stealing his body.

For his role in the strike, the president of the American Railway Union, Eugene V. Debs, was charged with mail obstruction and sentenced to six months in prison. That turned out to be a fateful decision, because he passed the time by reading the works of Karl Marx and some history books. By the time he got out, he had converted to Marxism. In 1898 Debs founded the Social Democratic Party of America, the first socialist political party in the United States; after that he ran as the socialist candidate for president five times.

Grover Cleveland would have liked to been the Democratic Party's candidate for president in the 1896 election, but by the end of his second term, the party was dominated by its Western (read: pro-silver) faction. Because Cleveland had given big business almost everything it wanted, he might as well have been a Republican, as far as they were concerned. When the 1896 Democratic convention met in Chicago, instead of nominating Cleveland for the fourth time in a row, the delegates dumped him. However, they didn't have anyone to take Cleveland's place. That gap was filled when one of the delegates, thirty-six-year-old William Jennings Bryan, spoke in favor of free silver. His address, now called the "Cross of Gold" speech, is the most famous in the history of presidential conventions. Bryan argued that America's farms were more important than her cities, because if you burned down the cities and left the farms, the cities would grow back, but if you destroyed the farms, every city would become deserted. He ended the speech with these words that convinced the delegates they had found their candidate:

"If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we will fight them to the uttermost. Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold."(65)

The Republicans only had two candidates when their convention met: House Speaker Thomas Reed and the tariff champion, William McKinley. It was the current Republican Party chairman, Mark Hanna, who made sure the nomination went to McKinley. A millionaire from Cleveland, Hanna used $100,000 of his own money to finance McKinley's campaign to this point. He was a firm believer in the idea that the purpose of government was to take care of business; if Washington did that, business could take care of everyone else. A few years earlier, he reprimanded the attorney general of Ohio for launching a lawsuit to break up the Standard Oil trust, telling him, "You have been in politics long enough to know that no man in public life owes the public anything." By twisting the arms of every rich man he knew, warning them that Bryan's platform would ruin the economy, he raised a huge fund of $3.5 million for the campaign, ten times what the Democrats could afford to spend.

William McKinley.

In a nutshell, Hanna bought the 1896 election. No dirty tricks were pulled, he just spent enough to overwhelm Bryan's message everywhere. While McKinley did all of his campaigning from his front porch, Bryan traveled more than 18,000 miles to speak to five million people, making ten to twenty speeches a day, the most any presidential candidate had done up to that date. Meanwhile, Hanna sent out a hundred million pieces of campaign literature, and staged a spectacular pro-McKinley parade in New York City. There are also reports that some employers, who tended to favor gold, told their workers that their jobs were at risk if Bryan got elected. On election night Bryan carried all of the South and West except for California and Oregon, but the more crowded northeastern and Midwest states went Republican, so McKinley won with both a popular and electoral majority.

This is the end of Part III. Click here to go to Part IV.

FOOTNOTES

46. Around this time, the theory of evolution was introduced in the United States (see Chapter 1 of The Genesis Chronicles), and successful businessmen believed that Darwin's theory of natural selection applied perfectly to what they were doing. Rockefeller, for instance, once said to a Sunday school class, "The growth of a large business is merely a survival of the fittest . . . The American Beauty Rose can be produced in the splendor and fragrance which bring cheer to the beholder only by sacrificing the early buds which grow up around it. This is not an evil tendency in business. It is merely the working-out of a law of nature and a law of God." Corporations like Standard Oil and Carnegie Steel were the "roses" he was thinking of, which prospered because hundreds of lesser companies had been pruned and thrown away. Later we will see the reaction of those workers who did not like being sacrificed in the name of progress.

47. Neither candidate generated much excitement. Tilden was cold and calculating, and a bachelor, because as one of his friends put it, "he never felt the need of a wife . . . Women were, so far as he could see, unimportant to his success." Late in life he confided to a colleague that he had never slept with a woman, which led historian James Fisher to comment, "Samuel Tilden was either asexual, or he was the first gay man to run for president." Hayes was a dignified father of five, but otherwise he had no personality either. His wife got most of the attention during his presidency, earning the nickname "Lemonade Lucy" because she banned all alcoholic beverages from the White House.

48. Faulty maps and conflicting information caused whites to forget where the massacre was; the Indians remembered, but for a century afterwards the only evidence available was their oral traditions. Archaeological efforts to locate the site began in the 1970s. The archaeologists found nothing but arrowheads and bullets, until twelve-pounder cannonballs, a type of ammunition the cavalry was likely to have, turned up in 1999, a mile north of where the site of the massacre had been expected. That spot was finally declared a national park, the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, in April 2007, 142 years after the battle.

49. See the Little House On the Prairie series, either the books by Laura Ingalls Wilder or the TV show, for examples of the challenges the Great Plains gave to its settlers.

50. After the battle, the Indians stripped the bodies and mutilated the uniformed soldiers, believing that the soul of a mutilated body would be forced to walk the earth forever, instead of going to heaven. Curiously, they stripped and cleaned Custer's body, but otherwise left it alone. They even mutilated the body of Isaiah Dorman, Custer's black scout and interpreter, whom they had regarded as a friend before the battle. Because Custer was no friend of theirs, no one knows the real reason why they treated his remains respectfully. Some believe it was because Custer had been wearing buckskins instead of a cavalry uniform, leading the Indians to think he was not a soldier. And because he had a haircut recently, they may have thought his hair was too short to be worth scalping.