| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 6: THE AGE OF HELLENISM

336 to 63 B.C.

This chapter covers the following topics:

Alexander the Great

With Greece under his belt, Philip of Macedon spent the last two years of his life preparing to conquer the last state that was strong enough to oppose him: the Persian Empire. To modern readers it seems like extreme recklessness to invade and conquer Asia with only a few thousand men, but Philip had plenty of reasons to be confident. He had the best army in Europe; the Persians had long relied on Greek mercenaries to do their fighting for them; and the adventures of Xenophon and Agesilaus showed what was possible. Indeed, an advance force of 10,000 Macedonians, led by the generals Attalus and Parmenion, crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor in the spring of 336 B.C. Philip was planning to join them in the autumn with the main army, but his assassination in October (inspired either by the Persians or by his colorful wife, Olympias) kept him from fulfilling his dream, and his soldiers languished in the land of the Trojans without him. Fortunately for them, Philip had prepared for the invasion so carefully that his twenty-year-old son Alexander had no problem picking up where he left off. He spent two years bringing the Greeks back into line; then in 334 B.C., he crossed the Hellespont with 30,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry.

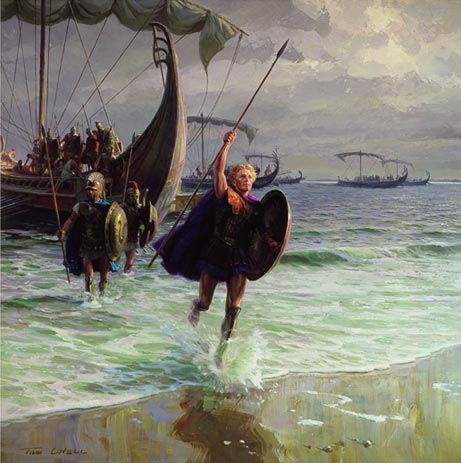

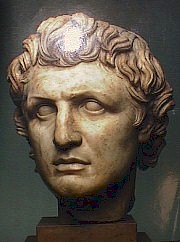

Alexander the Great.

Alexander meant to come ashore near the ruins of Troy, not only because Philip's advance force was already there, but also because the Iliad was his favorite book. At a nearby temple he found a shield belonging to one of Homer's heroes, and traded part of his own armor for it. That would be the first of many good omens he would encounter on his epic journey.

Alexander begins his journey. From the January 1968 National Geographic.

King Darius III did not take the invading army and its youthful commander seriously. He gave orders to have Alexander arrested and brought to Susa; an army the size of the Macedonian expeditionary force was sent to do the job. The armies met at the Granicus River, two days' march from Troy, and a furious charge by Alexander's cavalry decided the outcome. Probably the most intense moment of the battle came when Alexander was stunned by a blow from an axe, but his friend Cleitus saved the day by killing the axe-wielding Persian. No doubt the history of the Persian Empire and all of Western civilization would be very different, if Cleitus had been a minute too late.

The Persian army at the Granicus included 5,000 Greek mercenaries. While Alexander allowed the routed Persians to flee, the commander of the abandoned mercenaries, Memnon of Rhodes, tried to make a deal with him. Instead, the young king ordered his infantry, which had not played an important part in the battle, to execute the mercenaries for being "traitors to the Hellenic cause." Those mercenaries that were not killed outright were enslaved and sent back to Macedonia to do hard labor. Now Alexander's position was secure, because the next major Persian army was 1,000 miles away.

There was a Persian (Phoenician) fleet in the Aegean that needed to be dealt with. Because of that Alexander marched down the coast, eliminating the Persian naval bases one by one. At Ephesus he found Diana's famous temple half finished, offered to complete it if the Ephesians would carve his name on the front, and they refused with flattery: "It is not fitting that one god should build a temple to another god." The Ionian city-states were "liberated" (that is, enrolled in a tax-free but powerless league), and only Halicarnassus, which had a Persian garrison, tried to resist. In the areas he directly ruled Alexander retained the Persian system of satrapies.

After Ionia he veered inland. In Caria the local queen adopted him as an honorary son. Then he came to Gordium, where the Phrygians presented him with a strange puzzle. This was the Gordian knot, which we last saw in Chapter 3. Now the knot was at least four hundred years old, and a legend stated that whoever untied this tangled-up mass of rope would become king of Asia. Alexander sliced it in two with his sword and gained another omen in his favor.

In the fall of 333 B.C. Alexander went through a narrow pass in the Taurus Mts. known as the Cilician Gates. Darius, now fully alert to the danger from the west, was waiting on the other side with an army big enough to handle anything; estimates of its size range from 100,000 to well over 300,000 men. Despite the odds, Alexander won the battle of Issus through a triumph of tactics. The Persians were cramped between the mountains and the sea, without enough room to maneuver their superior numbers. Alexander placed himself and his cavalry on the right flank, giving him enough power to lance through a weak spot in the enemy line. Once in the rear of the Persian formation, he swung left and started rolling up the enemy battle lines. When Darius saw Alexander on his trusty horse, Bucephalus, galloping straight for him, he lost his nerve and fled in his chariot; nightfall allowed him to escape. The Persians had been so confident of victory that the officers brought their families to watch the spectacle; now Alexander captured them, along with a sizeable portion of the Persian treasury, the Great King's wife, mother, and children, 360 concubines of the king, 400 eunuchs, and even the ambassadors to the Persian court from Athens, Thebes, and Sparta.(1)

The battle of Issus, from a mosaic found at Pompeii.

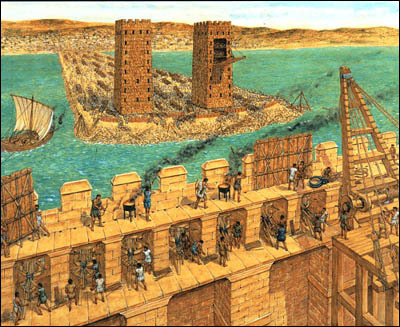

Alexander's next battle was his longest. Tyre had withstood sieges from Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar that had lasted over a decade; Alexander conquered it in seven months by building a causeway from the mainland and moving siege towers to the city walls. Later sand drifts enlarged the causeway; today's Tyre sits on a peninsula, not an island. When the city fell, Alexander gave it a harsher fate than his other conquests, killing 6,000 Tyrians and selling 30,000 others into slavery. 2,000 of the Tyrian victims were crucified on the beaches around the city, in one of the most gruesome scenes from Alexander's campaign. Fortunately for the Phoenicians, they managed to evcuate their women and children to Carthage, in North Africa, before the siege ended.

The siege of Tyre.

While Alexander was besieging defiant Tyre, Darius sent an envoy with an incredible peace offer. In return for peace and the safe return of his family, Darius was willing to give Alexander ten thousand talents of silver (at least $169 million in 2010 dollars, if my calculations are correct), all the land that the Macedonian had conquered to this point, and his daughter's hand in marriage. If Philip of Macedon had received such an offer, he would have taken it. Likewise, after all this success, those generals with a gambler's mindset were thinking it was time to quit while they were ahead. Still, Alexander consulted his staff. "Were I Alexander, I would accept," advised his senior general, Parmenion.

"So would I, were I Parmenion," Alexander replied. Every victory had increased his ambitions. Now he wanted nothing less than a universal state where all races lived in harmony and equality, with himself in charge of it. There was no room for two Great Kings in this vision.

After he left Tyre, Alexander headed down the coast to Gaza, which he besieged for two months. When Gaza fell, it got similar treatment to what Tyre had suffered; all of its men were executed, while all the women and children were sold into slavery. Batis, the Persian commander, refused to kneel before Alexander, so Alexander had his ankles pierced by a rope, and Batis was dragged to death behind a chariot. Apparently Alexander was imitating what Achilles did to Hector in the Illiad.

Alexander was expected to go to Egypt next, but instead he suddenly turned east and marched on Jerusalem. The Jews, who had been loyal to Persia until this time, chose to dress up in their finest and welcome Alexander with open arms. They took him into the Temple and showed him the prophecy in the eighth chapter of Daniel that predicted his coming. Alexander was so impressed that he not only spared the city, but declared Judah tax-exempt for one year out of seven, allowing the Jews to keep the "Sabbath year" of the Torah. His generous treatment of the Jews inspired the Samaritans to submit to his rule as well, but all they got for their act was Alexander's permission to enlarge the Samaritan temple.

Now Alexander continued into Egypt, where the joyful Egyptians welcomed him as a liberator from the hated Persians. He accepted the crown of the pharaohs, started construction on Alexandria, and made a pilgrimage to the oracle at the Siwa oasis, Egypt's holiest shrine. Now that his rear was finally secured, he was ready to strike into the heart of the Persian Empire and seize the throne of the Achaemenids.

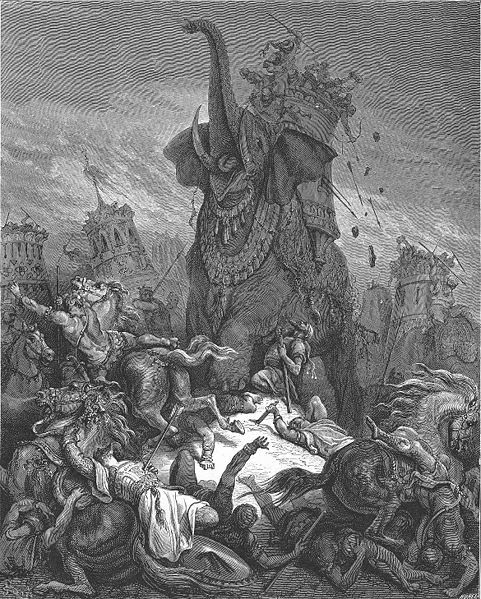

Darius prepared for his second encounter with Alexander more carefully than he had at Issus. First, he mobilized all the soldiers he had left. Because the empire's western provinces had been lost, Darius could only draw men from the east, but at 250,000, it was a force that far outnumbered Alexander's 47,000 men. The place he chose for the battle was a plain called Gaugamela, east of the Tigris River and not far from the ruins of Nineveh. To make sure his troops had maximum mobility, he improved the field by plowing it table-flat. For his main weapons, he selected two hundred chariots with blades attached to their wheels (obsolete by this time, but still frightening to an infantryman), and an innovation from India: fifteen war elephants. A few days before the battle took place, both sides saw a lunar eclipse, leading them to believe that something very important was about to happen.

The battle that changed the world took place on October 1, 331 B.C. Alexander used a strategy based on the superior speed and discipline of his own troops and the special temperament of Darius. He started by shifting his whole force to the right in a maneuver designed to throw the enemy off balance. Darius fell for it and ordered the troops on the flanks to follow, until many of them stumbled in the rough terrain beyond the carefully prepared field. Meanwhile, the chariots in the center charged at the Macedonian phalanx. When they were too close to change direction quickly, the Macedonians opened ranks; the chariots rushed harmlessly to the rear, where waiting cavalry finished them off. Almost no Macedonians were killed or injured. Then Alexander saw a gap between the Persian center and left flank. He charged into it, making straight for the king's chariot. As at Issus, Darius turned tail and fled. On the flanks, the battle went badly for the outnumbered Macedonians, until the news of Darius fleeing caused a Persian collapse. The final score: Macedonia lost 1,000 men, Persia lost 50,000.

Most Persians considered the desertion of Darius an abdication, so after Gaugamela they generally regarded Alexander as the new king of Persia. Therefore he did not face resistance at the next two cities he came to, Babylon and Susa. The Persian satrap of Babylon, Mazaeus, welcomed the Macedonian army and sent gifts. At this date, Babylon was still larger than any Greek city; Alexander was relieved that he would not have to besiege a city of this size. Since the main street of Babylon was built for processions, Alexander celebrated his arrival by holding a parade. Then he made an offering to the god Marduk in the Esagila, and because this temple was still damaged from what Xerxes had done to it, more than 150 years earlier, Alexander ordered repairs made on all of Babylon's temples. He also decided to keep Mazaeus as the governor, and rested the troops for a month, before moving on to Susa. At Susa he captured the largest portion of the Persian treasury; estimates of the amount captured range from 50,000 talents to 180,000 talents of gold, depending on who you're reading. Several ancient authors reported that Alexander had trouble paying for the war during the early years, but that wasn't a problem after Susa! He sent 3,000 talents back to Macedonia, because Antipater, the regent left in charge of the homeland, had been busy fighting the city-state of Sparta while Alexander was away. Despite all this, Darius had gotten to Susa first, and then turned north, taking 8,000 talents with him. Darius was trying to escape to Bactria (modern Afghanistan), where he had one more army, led by Bessus, the satrap of Bactria.

We noted in the previous chapter that Susa was on the southern end of the Persian Royal Road; from here one had to follow another road, through a narrow pass in the Zagros Mts., to reach Persepolis. The Uxians, a non-Iranian, semi-nomadic tribe, lived here, and though they were near two Persian capitals, Persian rule over them had always been loose. Now they opposed Alexander's advance. The resulting battle, the battle of the Uxian Defile, was just like the famous battle of Thermopylae, except that the roles were reversed; this time the Greeks were attacking and the soldiers on the side of the Persians were the defenders. As at Thermopylae, here a small force of defenders could keep a larger force out indefinitely, and here Alexander got through the same way the Persians did in the first battle: he found out there was an alternate path through the mountains. Alexander and a general named Craterus took 8,000 of the soldiers on this path, which allowed them to ambush the Uxians and capture their village; then the rest of Alexander's army was able to follow the main path.

At Persepolis Alexander captured the rest of the Persian treasury. Persepolis was only supposed to be another rest stop, but near the end of the stay a wild party got out of hand and the palaces of Xerxes went up in flames. Alexander didn't like being held responsible for this colossal act of vandalism, but later called it a suitable punishment for what the Persians had done to Athens, 150 years earlier. A short march from Persepolis brought him to Pasargadae, where he paused to meditate in the tomb of Cyrus, one of his personal heroes.

If Alexander's troops thought the war was over, they were mistaken. Darius was still at large, hiding at Ecbatana. In the spring of 330 B.C., Alexander turned north to catch him. Darius wanted to surrender, but Bessus would have none of it. Bessus arrested the king and withdrew in the direction of his home province. Alexander pursued, covering an amazing 36 miles per day in forced marches. Near the Caspian Sea the two armies came in sight of each other. Bessus stabbed Darius to death and left his body behind for Alexander. Then he added another insult, by proclaiming himself King Artaxerxes V, heir to the Achaemenids. Alexander regarded Bessus as a rebel and chased him into Central Asia, where he captured and executed him. For the next six years he wandered aimlessly beyond the known world, scaling citadels, ambushing hill tribes, and outrunning the horsemen of the steppes. Then he marched into India, where a sit-down strike from his soldiers finally forced him to turn back.

The trip home was the toughest part of the entire campaign. The army split into three groups: one, commanded by General Craterus, marched directly west to the mountains of eastern Iran. Admiral Nearchus took the second group down the Indus River to the Arabian Sea and sailed west to the Persian Gulf. Alexander, aching from old wounds and sharing every hardship with his soldiers, led the third group through the sun-scorched Baluchistan desert. The three groups reunited near modern Bandar Abbas, and continued to Persepolis and Susa.

In the years since Gaugamela, Alexander had gradually come to see that he could not simply rule the Persian Empire as a conquered territory of Macedonia--both Asians and Europeans would have to share the tasks involved with running it. He took to wearing Persian clothes, which the Greeks regarded as silly and effeminate. He also seemed to enjoy the ceremonies of the Persian court. Three thousand Persians were taught Greek and instructed in western military science; a Persian noble was even promoted into his inner circle of advisors. The Greeks regarded this behavior as a betrayal, and this led to several unpleasant incidents on the march, like the drunken quarrel where Alexander killed Cleitus.

When he reached Susa in 324 B.C., he finally tried to consolidate his vast domains. He took Barsine, the daughter of Darius, as his second wife, and 80 officers and 10,000 other veterans took Persian wives on the same day in a ceremony portrayed as a marriage between east and west. Afterwards he sent Craterus to Macedonia, leading 11,500 troops that were going home.

In Susa and in Babylon, the next stop, Alexander reorganized the army, issued coins, built a merchant fleet, dug new irrigation canals, and made plans to explore and conquer Arabia. He also considered moving the capital of the empire from Pella (in Macedonia) to Babylon, a more central location. Because Nebuchadnezzar's great ziggurat, the Etemenanki, had gotten quite dilapidated after 250 years, Alexander ordered it torn down and rebuilt, but he died before the rebuilding phase could begin. While inspecting a drainage project near Babylon, a mosquito bit him and he contracted a fever, presumably malaria. During the next few days he was confined to his couch in Babylon, barely able to speak, as his captains filed past, offering last farewells. Death came in June of 323 B.C.; he was not quite thirty-three years old.

The Wars of the Diadochi (Successors)

Alexander never seemed to give much thought to the idea of his empire existing without him; at least he left it ill-prepared to face that situation. Because he was in the prime of life, theories have been generated since his death, suggesting that it wasn't really a disease; he could have been poisoned accidentally by his doctors, or deliberately by one of the individuals mentioned below. Whatever brought Alexander down, an arrow wound to the chest that he suffered in India, and depression caused by the recent death of his best friend Haphaestion, would have made him more vulnerable than usual.

On his deathbed, when asked who should inherit the throne, all Alexander said was "the strongest." The generals took this as a signal to take matters into their own hands, and in little more than a decade they carved up Alexander's realm into kingdoms for themselves. The two generations following the death of Alexander were a time of conflict, marked by bribery and treachery; the individual armies were largely composed of mercenaries who changed sides at the drop of a hat (usually one filled with coins). It is a very confusing period from a historical viewpoint, but the motives of the participants are easy to discern; only Antigonus Monophthalmos wanted to keep the whole world united under one state and one ruler, while the others were simply out to grab as much land as possible from their rivals.

The trouble started because the only heirs Alexander had in the Macedonian royal family were a feeble-minded half-brother and a posthumous son. At first everyone tried to maintain a central authority; they crowned both of the above misfits, and three generals (Antipater, Perdiccas and Craterus) became regents, jointly governing the empire in the name of the dynasty. Other officers quickly proclaimed themselves governors of the provinces they were in: Antigonus Monophthalmos (Pamphylia, Lydia & Phrygia), Eumenes (Paphlagonia, Cappadocia & Syria), Neoptolemus (Armenia), Lysimachus (Thrace) and Ptolemy Soter (Egypt and Libya). They worked together long enough to suppress a rebellion in Greece and a mutiny in Bactria, before rivalry got the better of them.

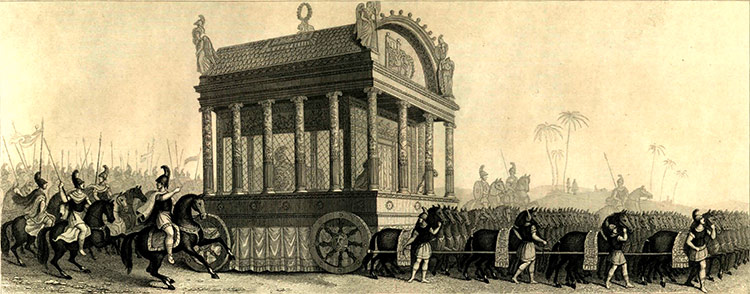

Alexander's funeral procession. This 19th-century sketch is based on a description by the Roman-era historian Diodorus.

If you want to blame anyone for starting the infighting, blame Antigonus. He couldn't get along with Perdiccas and Eumenes, and his opposition split the ruling triumvirate; Antipater and Craterus joined him because they thought Perdiccas was getting too strong. Then in 321 B.C., a magnificent funeral procession was organized to carry Alexander's body from Babylon to Macedonia; it got as far as Syria before Ptolemy and his troops intercepted and diverted the royal corpse to Egypt. Furious, Perdiccas organized an expedition to get the corpse back. But in Egypt he tried to cross the Nile by letting his war elephants wade through the water, and when he realized the Nile was too deep for this, he ordered those men who were already on the other side to cross back again. As you might expect, his contradictory orders caused confusion, and a lot of men in the water were carried away by the current, to be drowned or eaten by crocodiles. The officers under Perdiccas were outraged that he would waste the lives of the troops needlessly, and three of them ended the expedition by murdering Perdiccas. One of the killers was named Seleucus Nicator; he wasn't important before this time, but he would be very important afterwards, so remember his name!

Closer to the homeland, Craterus and Neoptolemus ganged up on Eumenes. They probably thought Eumenes would be a pushover, because he did not have firm control over Cappadocia (Alexander had bypassed this territory on his way to Issus). Moreover, Eumenes was more of a nerd than a soldier; although he had gone with Philip II and Alexander everywhere, he had done so as the personal secretary of those two conquerors. By contrast, Craterus was the most experienced living hero from Alexander's campaigns, and he probably expected the Macedonian soldiers under Eumenes would defect to him. But while Eumenes may have been out of his element, he had a trick up his sleeve; he had recruited 6,300 Cappadocian cavalrymen, and paid them very well. Because the Cappadocians were not Macedonians, Craterus meant nothing to them, and in a battle near the Hellespont, both Neoptolemus and Craterus were killed.

Before 321 was over, the surviving officers of Alexander called a conference at Triparadisus in Lebanon, and they set up a new coalition: Antipater became the sole regent and guardian of the two young kings, Antigonus and Antipater's son Cassander became the commanding generals of the army, and Seleucus Nicator became governor of Iraq. Two years later Antipater died and the situation became chaotic again. Cassander claimed Macedonia and Greece for himself, while Antigonus drove his eastern neighbor, Eumenes, out of his domain. Antigonus then marched to Babylon, ejected Seleucus, and chased Eumenes to Iran, where the latter was deserted by his own troops, betrayed, and put to death (316).

The initial successes enjoyed by Antigonus inspired this one-eyed senior citizen to make himself the sole ruler of the entire empire. He had the advantages of a central position and command of the sea. Clever propaganda and an invasion by his son Demetrius stole Greece from Cassander, and he also brought Ionia under direct rule and organized the islands of the Aegean (except Rhodes) into a puppet league. At this point, the only parts of Alexander's empire he did not control were Macedonia, Thrace and Egypt, but his failure to disguise his ultimate ambition caused the other generals to gang up against him. In 312 Demetrius was defeated at Gaza by Ptolemy; in the same year Seleucus returned to Babylon, recovered it, and started a ten-year campaign to bring the eastern provinces under his rule.

They agreed to a truce in 311, but it only lasted for one year. By this time everyone closely related to Alexander had come to a violent end. Being a distant relative of the royal family, Antigonus crowned himself king in 306, without naming any particular territory, and before long Ptolemy and Seleucus did likewise. Meanwhile Demetrius defeated Ptolemy in a naval battle off Cyprus, but failed to take Rhodes by siege, unable to live up to his nickname Poliorcetes (the Besieger)(2). Seleucus defused a sticky situation in the east with India's strongest monarch, Chandragupta Maurya, by swapping Pakistan for 500 war elephants(3); then he hurried west to join the anti-Antigonid coalition. For the upcoming showdown he brought 400 elephants, 10,000 horse archers, and even a hundred out-of-date scythed chariots; you could say that Seleucus threw in everything but the kitchen sink! Antigonus went down fighting in the heart of Anatolia before the united armies of Cassander, Lysimachus and Seleucus (the battle of Ipsus, 301 B.C.). The victors divided the kingdom: Lysimachus took western Anatolia, Seleucus took southern Anatolia and Syria, while Ptolemy, who had arrived too late for the battle, managed to get Israel, Lebanon and Cyprus. Demetrius still had his fleet, allowing him to terrorize the Aegean for years to come, but he only had the resources--and mentality--of a freebooter. The dream of Alexander was dead.

The battle of Ipsus fulfilled the prophecy in Daniel 8: Greece would conquer Persia only to shatter into four secondary kingdoms. It took another generation of fighting to reduce the number of kingdoms to three. Demetrius seized Greece and Macedonia after Cassander's death, but a few years later Lysimachus and Pyrrhus of Epirus (a kingdom in Albania & northwestern Greece) drove him out again. Then his fleet deserted to Ptolemy; bereft of support, he surrendered to Seleucus and spent his last days under house arrest. Ptolemy was the next to go, dying (remarkably) of natural causes in 283. Finally Lysimachus and Seleucus turned against each other. Seleucus invaded western Asia Minor, then controlled by Lysimachus, in 282, advancing until he met the army of Lysimachus at Corupedium, near Sardis, in the following year. By this time, both of the commanders were senior citizens (Seleucus was 77 years old, while Lysimachus was 80), and they rode into battle on elephants. The only information we have about the battle of Corupedium is that it was decided when Lysimachus was killed by a javelin thrown by someone on the other side.

With Macedonia and the mantle of Alexander now up for grabs, Seleucus spent seven months reorganizing the cities of Asia Minor; then he crossed the Hellespont into Europe. He got as far as Lysimachia, the capital city of Lysimachus. But before he could go on to Macedonia, he was stabbed to death while performing a sacrifice, by Ptolemy Keraunos. This Ptolemy was a son of the elder Ptolemy, who had failed to inherit anything from his father, so he had gone to the court of Lysimachus, looking for an opportunity. Now he claimed the whole European portion of Alexander's empire as his kingdom, but he only ruled it for a year and a half. A group of Celtic tribes, who we call the Gauls, appeared as a new enemy, migrating from central Europe to the Balkans. Ptolemy Keraunos allowed them to conquer the Thracians, thinking they would get rid of another enemy for him, but then in early 279 they invaded Macedonia as well; in the resulting battle Keraunos was defeated, captured and beheaded. At least three more short-lived kings rose and fell after that. Finally Antigonus II, a son of Demetrius, drove the Gauls into Asia Minor, grabbed Macedonia in 277, and kept it in his family afterwards. Now peace came, since all of Alexander's successors were dead. Although new petty wars would break out in the future, a measure of stability existed; the Antigonids had the European portion of Alexander's empire, the Ptolemies had the African portion (plus Cyprus and the Levant), and the Seleucids had most of the Asian portion.

The Diffusion of Greek Culture

or, Greece Is the Word

Behind the sorry tale of discord and decline following Alexander's death, is a real success story: the triumph of Greek culture, also known as Hellenism (after Hellas, the Greek name for their homeland). The Greek colonization that had been going on since 800 B.C., followed by Alexander's conquests, created an economic and cultural sphere spreading from southern France to India, and from Arabia to Siberia. This was the closest thing to a universal society the world had seen since Babel. Throughout this huge area people understood the Greek language, and Greek art was a common sight. The three hundred years between Alexander and Cleopatra were an exciting time of progress as well. At the beginning of this era came new philosophers, notably Epicurus and Zeno (the founder of Stoicism). The field of science produced such outstanding figures as Eratosthenes, Archimedes, Euclid and Aristarchus. Alexandria in particular became famous as the learning center of the world, with its library of more than 500,000 scrolls.

Alexander encouraged Hellenism by building new cities wherever he went. Before he was done he named one after his horse Bucephalus, one after his dog Peritas and seventeen after himself. Seleucus followed that example aggressively, because when he took over the only Greek parts of his kingdom were Ionia (a district too far from the center to be much help), and his army of about 50,000 soldiers. In the course of his reign Seleucus started at least sixteen new colonies named Antioch or Antiochia (after his father, Antiochus), five Laodiceas (after Laodice, his mother), four Apameas (after his Persian wife Apama), one Stratonicea (after Stratonice, a Macedonian woman he married after Apama's death), and nine Seleucias (after himself, naturally). Later Seleucid kings, despite the troubles they had with their unwieldy empire, somehow found the time to establish at least twenty more communities. This was done as fast as they could persuade Greek immigrants to settle in them, and served the purpose of promoting unity throughout the realm. Each city was designed pretty much the same way, with streets in a grid pattern and all of the features the Greeks needed for good living: an agora, gymnasium, theater, council halls, public halls and baths. Yet these cities lacked the autonomy that many Greeks considered essential for good government; the Macedonian founders came from a land without cities, and thus had little experience with or sympathy for democracy. Consequently it was the kings, and not the people, who ruled the Greek cities of Asia, and they did so as autocratically as the Oriental monarchs of previous eras.

Many new settlements were nothing but military camps, which failed to take root; east of the Euphrates the whole project was only superficially successful, producing a string of Greek cities surrounded by a countryside that steadfastly remained non-Greek. The only place they settled on the Iranian plateau was Rayy (also called Rai, a suburb of modern Tehran); the rest of Iran remained a vaccuum for the Parthians to fill when they arrived. As a result, Alexander, Seleucus and Antiochus I may have brought in enough Greeks to maintain their rule in an alien land (an estimated 100,000 families), but the complete cultural fusion which they wanted never took place; in the long run, this contributed to the disintegration of the kingdom. In Syria, however, western civilization came to stay (until Islam arrived, anyway), and the three cities of Antioch, Laodicea and Apamea were the pride and nerve center of the Seleucid kingdom. Antioch quickly grew to house between 90,000 and 150,000 inhabitants, making it the second largest city in the known world; only Alexandria in Egypt was larger. Another spectacular success was Seleucia on the Tigris River(4). It replaced Babylon as the largest city in Iraq, and became the second capital of the empire, where the heir to the throne resided. Its location in the geographic center of the realm, where roads from every direction met, turned it into a major commercial center as well, dominating the economy of half a continent in its heyday.

Around 200 B.C., Macedonia and Greece ran out of people to export, so after that the cultural winds started blowing in the opposite direction. For example, the Babylonians gave the Greeks several elements of their culture, notably astronomy, astrology, and geometry. A Babylonian priest named Berosus wrote a three-volume work in the Greek language called the Babyloniaca, which preserved the history of his native land; his Alexandrian counterpart, Manetho, did the same thing for Egypt. The Greeks also became dissatisfied with their religion, which portrayed the gods as silly oversized people and offered no promising afterlife nor comfort to those in distress. They started investigating other religions for answers to their questions about life, and invented some new creeds before they were done: the cult of Serapis in Egypt, Mithraism in Persia, perhaps even Mahayana Buddhism in northern India. Sometimes this syncretism produced bizarre hybrids; e.g., the many-breasted fertility goddess Cybele became an Asian version of Artemis, the chaste huntress of Greek mythology (the New Testament calls her "Diana of the Ephesians"). The restoration of Persian culture under the Parthians and the furious Jewish rejection of Hellenism by the Maccabees are the best examples of the reversals suffered by the Greeks in the latter part of this period.

The Seleucid Kingdom

In its heyday, around 300 B.C., the kingdom of Seleucus Nicator covered about one and a half million square miles. Seleucus could claim to be Alexander's true heir because he got the lion's share of the land and the people, but he also inherited more problems than any of his rivals. The chief one was the ethnic disunity mentioned in the previous section, which produced such things as Greek factionalism, different forms of government in different provinces, and natives with anti-Greek attitudes. Add to that foreign enemies in every direction and the result was a flabby giant that was slow to respond to anything. Nor did the troubles of Seleucus end when he evacuated his untenable holdings in the Indus valley (Pakistan); before his reign ended Armenia, northern Anatolia(5), and northwestern Iran(6) drifted into independence.

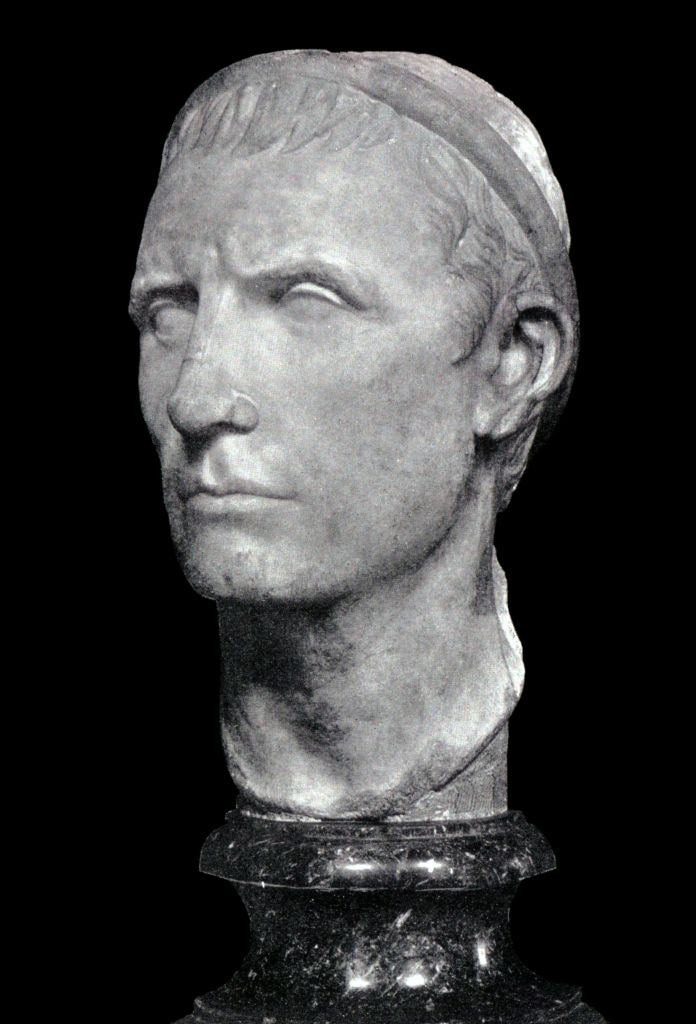

Seleucus I.

The situation got worse in the days of the second Seleucid king, Antiochus I (281-261). We already mentioned the Gauls, who crossed the Danube, wiped out what was left of the kingdom of Lysimachus, and killed Ptolemy Keraunos. In 278 three tribes of Gauls came into Asia and settled themselves permanently in the center of Asia Minor, becoming the Galatians of the New Testament. These Gauls raided their neighbors on and off for the rest of the century and effectively screened northern states like Bithynia and Pontus from Seleucid interference(7).

The political fragmentation of Asia Minor continued when Egypt's Ptolemy II used his navy to relieve Antiochus of much of his Syrian and Cilician seaboard; even Seleucia-in-Pieria, the seaport of Antioch, fell under Ptolemaic rule for a while (the First Syrian War, 274-271). The Ptolemies completed their control over the coast of Greek Asia Minor by supporting the city of Pergamun when it revolted against the Seleucids; Antiochus was killed in battle when he attempted to recover it.

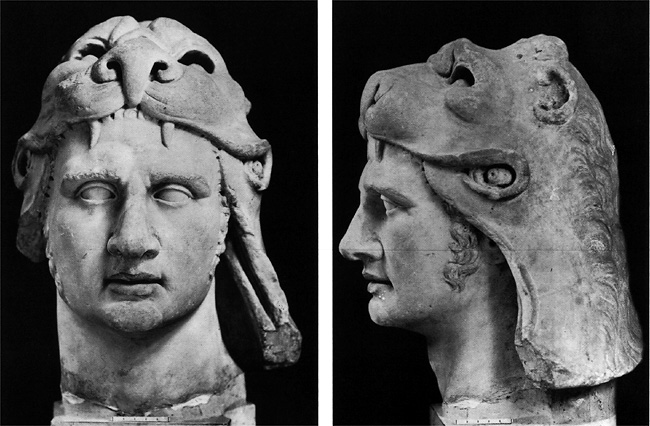

Antiochus I. From Nemrud Dagh, Turkey.

The next king, Antiochus II (261-246), saw eastern Iran and Afghanistan break away to form the kingdoms of Parthia and Bactria respectively. He was forced to let them go while he fought the Second Syrian War (260-255) with Ptolemy II. He recovered much of the land lost by his father and defeated the Egyptian fleets in the Aegean, only to find the city-states of Greece forming anti-Seleucid coalitions (the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues) to keep him from expanding into Europe. The war ended with a marriage; Antiochus gave up his first wife, Laodice, and married Ptolemy's daughter Berenice.

The marriage was not a happy one, and after a few years Antiochus left Berenice and their infant son to rejoin Laodice. Laodice, however, poisoned him, proclaimed her own son king (Seleucus II, 246-225), and ordered the deaths of Berenice and her son. The new Egyptian king, Ptolemy III, was enraged enough to start the Third Syrian or Laodicean War (246-241). This time the southern king came out ahead of his northern rival. Ptolemy crossed the Euphrates and invaded Babylonia, but without lasting effect. Meanwhile the Egyptian fleet took back Ionia, coastal Syria, and even part of Thrace; this marks the zenith of the Ptolemaic kingdom. Seleucus spent most of his remaining years in an unpleasant civil war with his brother Antiochus Hierax; because of that he never had the time to recover the kingdoms of Pergamun, Parthia, and Bactria.

Seleucus III (225-223) was fully occupied with Pergamun. Upon his assassination the throne came into the hands of eighteen-year-old Antiochus III. In less than a century the Seleucids had lost more than half the territory they had started with.

Classical Asia Minor

Because of its complex, difficult terrain and its out-of-the-way location, Alexander never invaded the northern half of Asia Minor, and he chose to leave it alone after the local Persian satraps rendered the minimum required homage. We have already covered the origin of the people who lived in the center of this landmass, the Galatians; now it is time to discuss their neighbors: Bithynia, Pontus, Cappadocia and Pergamun.

Bithynia, in the northwest corner of the peninsula, was blessed with good farmland, pasturage, timber, fine marble, and useful harbors. Its first ruler, Zipoetes I (328-280), avoided submission to Alexander, resisted both Antigonus I and Lysimachus, crowned himself king in 297 B.C., and repelled the Seleucids. To gain support in a quarrel over the throne, his son Nicomedes I took the ominous step of inviting the Galatians into Asia Minor in 278 B.C. He also made his realm a prosperous Greek state, ruled from Nicomedia, a port he founded by merging two older Greek cities.

A feudal Persian nobility dominated the fertile northern coast of Asia Minor, known as Pontus after this, but the people who lived in its villages spoke no less than twenty-two different languages. King Mithradates I (301-266), a partially Hellenized Persian who claimed descent from the Achaemenid dynasty, founded the state by declaring independence first from Antigonus I, and later from the Seleucids. Like the Bithynians, he found the arrival of the Gauls to be a blessing. He established his capital at the inland city of Amasia; later monarchs moved it to Sinope in the second century.

The successors of Mithradates built up the strength of the country, employed many Greeks and won recognition as a Hellenistic power. One of them, Pharnaces I (185-169), was ambitious enough to propose a Pontic empire stretching all the way around the Black Sea. The son of Pharnaces, Mithradates V (150-120), was the most powerful monarch in Asia Minor; he was followed by Mithradates VI Eupator Dionysus the Great (120-63), who enlarged the state with breathtaking success, coming very close to realizing the dream of Pharnaces. The story of how he gave the Romans their most dangerous challenge from any Hellenized state will be covered near the end of this chapter.

Cappadocia, deep in eastern Asia Minor, was a rugged tableland with extreme temperatures and poor crops, but many horses, sheep and mules. The Persian satrap, Ariarathes I, like the kings of Pontus, claimed Cyrus the Great as an ancestor; he was killed in 322 when Eumenes, one of Alexander's successors, was awarded the land to govern. After the battle of Ipsus, Ariarathes II recovered the country as a vassal of Seleucus I; in 260 his son Ariaramnes declared independence, but he and his successors remained allies of the Seleucids until the Romans defeated Antiochus III.

The most successful and the most anti-Seleucid state in Asia Minor was Pergamun, which started around a city by the same name in the land of the Mysians, about 15 miles from the Aegean. This community first became important under Philetaerus, a eunuch of mixed Macedonian and local (Paphlagonian) parentage. Philetaerus was first an officer under Antigonus I, then military governor under Lysimachus; in 282 he defected to Seleucus I, taking with him an enormous treasure to win new friends with. During the last nineteen years of his life, he ruled Pergamun as a Seleucid vassal, gaining distinction by beating off the first Galatian attack. Later Pergamene rulers dutifully remembered him by putting his portrait on their coins.

His nephew and adopted son, Eumenes I (263-241), threw off the Seleucid yoke, allied himself with Ptolemy III, and grabbed the nearest piece of Seleucid territory. The next king, Attalus I (241-197), won a spectacular victory against the Galatians, gave the Seleucids more than a few royal headaches, and even interfered in Greek affairs across the Aegean. Officially Attalus claimed to be Asia Minor's champion for Hellenism, but many Greeks detested him as a tool of the Romans, who were just starting to get involved in the region at this time.

The kings of Pergamun lived more modestly than most monarchs of their day, but they were equally absolute rulers. One key to their success was that they avoided usurpations and family quarrels, a common feature of all other Greek monarchies. Keenly devoted to culture, the Pergamene kings turned their capital into a magnificent display of art and architecture. Pergamun was home to the largest temple of Zeus, with an altar that was fifty feet high(8); surviving works of art from Pergamun, like "The Dying Gaul," are masterpieces by any measure. Pergamun's library grew to rival the great library in Alexandria. This made Alexandria so jealous that the Ptolemies banned the export of papyrus, thinking that would stop Asia Minor's scribes in their tracks; instead, the Pergamenes invented parchment, making it from animal skins. Parchment cannot be made into sheets as long as papyrus, so instead of rolling it up into scrolls, parchments were organized as stacks of pages; when ways were found to bind them together that way, books as we know them were invented. Books proved to be handier than scrolls, so gradually parchment replaced papyrus as Western civilization's preferred writing material. Overall, we can say that Pergamun was more successful than Alexander at spreading Greek civilization into the countryside of Asia Minor.

The Dying Gaul.

Antiochus the Great and Antiochus Epiphanes

Antiochus III (223-187) was the only Seleucid monarch who could reverse the decline of the kingdom. He did much to rebuild Alexander's empire, and only failed because the new power in the West, the Roman Republic, took an interest in the Middle East during his reign. This is when we first see the nation that would become the dominant ruling authority of the New Testament era.

Antiochus III.

Antiochus first proved his generalship by bringing Atropatene back under Seleucid rule, something none of his predecessors could do (220). Then he launched the Fourth Syrian War (219-217); because Egypt had a poor and unpopular ruler, Ptolemy IV, he expected to win an easy victory. The Seleucid army, with its war elephants, marched all the way down the Levant, but Ptolemy raised a composite Egyptian-Greek force and soundly defeated the invaders at the battle of Raphia, just south of Gaza (217). Antiochus retreated to Syria, and the border between the northern and southern kingdoms returned to the Orontes River.

Antiochus' ambitions grew with each success. In 213 B.C. he captured and executed the governor of central Asia Minor, who had been in revolt since the beginning of his reign. Then he turned his attention to the east, another area where things had been going against the Seleucids for decades. In 212 he conquered Armenia, dividing it into two provinces that would henceforth be called Greater and Lesser Armenia. Next he marched against the Parthians, who had overrun much of eastern and northern Iran in the previous generation. In 209 B.C. he defeated and confined the Parthians to the area they had started from, but instead of conquering them completely, Antiochus chose to make peace, since he considered his upcoming struggle with Bactria to be more important. He recognized the independence of the Parthian rump state in exchange for Parthia's submission to Seleucid authority, and the use of Parthian troops in the Syrian army.

During the next two years Antiochus fought his Bactrian counterpart, Euthydemus I, to a standstill. A lengthy siege of Bactra, the capital, got nowhere, and after a while Antiochus came to the conclusion that while he could defeat every enemy in the east, he did not have enough troops to permanently garrison the entire area. This moved him to make peace with Bactria as well. Euthydemus kept his crown, donated elephants to the Seleucids, and his son Demetrius married a daughter of Antiochus. Then Antiochus crossed the Hindu Kush into the Kabul valley, where he signed a pact with one of the last Mauryan emperors of India, gained some more elephants, and returned west by way of southern Iran and the Persian Gulf. Although the campaign was a success, it gained little in the way of results. Antiochus came back to hear himself hailed as a second Alexander, but the Parthian and Bactrian states had enough strength left to make trouble in the future.

The death of Ptolemy IV in 203 B.C. threw Egypt into a disarray that excited both Seleucid and Macedonian appetites. At the battle of Panias (198, near the headwaters of the Jordan), Antiochus chased the Ptolemies completely out of the Holy Land. Then he invaded southern Asia Minor while his ally, Philip V of Macedonia, shattered Ptolemaic rule in Ionia and introduced his own harsher government. The independent states of Pergamun and Rhodes appealed to Rome for protection; the senators of Rome did not care what happened to distant Greek cities, but they let themselves be persuaded, quite against the evidence, that the Seleucid-Macedonian axis would someday attack Rome. Philip V was already on the bad side of the Romans because he supported their archenemy, Hannibal, in the recently concluded Second Punic War. A Roman army crippled Macedonia in the battle of Cynoscephalae (197).

Antiochus, whose understanding with Philip had related to Egypt only, decided to reassert the old Seleucid claims to Ionia and Thrace. To quiet Rhodes, he gave the Rhodians the nearest stretch of coastline, Caria(9). His eastern exploits had blinded his court, if not himself, to the weaknesses of his polyglot state and led to his acclamation as a second Alexander; consequently, when he occupied a sliver of Thracian territory, the Romans saw it as the beachhead for an invasion of Europe. When Hannibal appeared at the court of Antiochus the Senate, egged on by Pergamun, decided to go to war with the Seleucids (192). Antiochus, however, moved first, accepting an invitation from the Aetolian League to ship 10,000 troops to Greece in the same year.

The Romans quickly pushed Antiochus out of Greece, crossed over to Asia Minor, and won a total victory at the battle of Magnesia (190). Rome took nothing for herself, giving Western Asia Minor to Pergamun and Rhodes instead(10), but the destruction of the Seleucid army immediately undid Antiochus' life-work. Atropatene, Parthia, and the Armenian states rejected Seleucid hegemony when they heard the news. Antiochus also had to give up his war elephants, Hannibal, and all but ten of his ships; his sons became hostages in Rome to ensure their father's good behavior(11).

From now on Rome never missed an opportunity to weaken the Seleucids. Antiochus left his heirs no more than the Fertile Crescent, Cilicia, and part of Iran, and most of that would go in the next generation.

The reign of Seleucus IV (187-175) was uneventful. His brother and successor was Antiochus IV (175-163). Growing up as a Roman hostage convinced Antiochus that stopping the Romans was his most important priority. To do this he would need to unify the nation, and that meant merging the many peoples of his realm into one culture; the Hellenism that previous kings encouraged was now insisted upon. In addition, he tried to increase support for the Seleucid crown by claiming godhood, a common practice among Oriental monarchs (the nickname of Antiochus IV, Epiphanes, means "the appearance of God"). Most of the kingdom's subjects went along with this, except the Jews. It is at this point that we see the Jews split into the two main sects of the New Testament era: the Pharisees (fundamentalist majority) and the Sadducees (liberal upper-class). A Sadducee named Jason literally bought for himself the office of high priest by sending Antiochus a larger gift than that of his brother and predecessor, Onias III, who was generally regarded as having a subversive pro-Ptolemaic attitude. Once in office Jason continued to curry favor by changing the name of Jerusalem to Antiochia and by building a gymnasium next to the temple. The sight of naked uncircumcised athletes offended many Jews, and they eventually got Jason exiled, but worse was to come.

Meanwhile, Antiochus was busy fighting in Egypt. In his first campaign (170), he defeated and conquered Egypt completely, but had to hurry home to quell disturbances elsewhere. He returned to Egypt in 168, but was stopped by a threat of Roman intervention. When a Roman envoy ordered him not to attack Alexandria, Antiochus asked for time to consider his reply. The Roman boldly drew a circle around the Syrian king and said, "Answer the Senate before you step out of that circle!" Antiochus capitulated, and withdrew from Egypt.

On his way home he stopped in Jerusalem to launch a vigorous campaign of persecution against the non-Hellenized Jews. He looted the Temple of its treasures, set up an idol of Zeus inside, and had a pig sacrificed on the altar. Copies of the Torah were destroyed wherever they were found, Sabbath observance was not permitted, circumcision was prohibited on penalty of death, and individual Jews were ordered to show their loyalty by eating pork in public--or else.

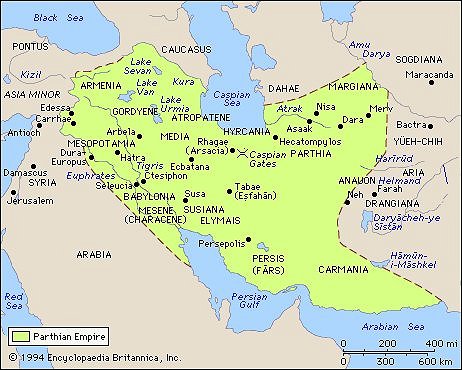

The Origin of the Parthians

Diodotus, the satrap of Bactria, revolted from Seleucid rule in 255 B.C., establishing an Indo-Greek kingdom in Afghanistan. Two or three years later, the northeastern corner of Iran also broke away, but a very different state appeared there. The rebels were a tribe of nomads who called themselves the Parni, led by a chieftain named Arsaces. The exact origins of the Parni are uncertain; they were not Iranians, but they were definitely Indo-Europeans. Possibly they were an offshoot of the Scythians, because they came from Central Asia and lived a very similar lifestyle (both were superb horsemen & archers). We first hear about them in the time of Darius I, but they did not amount to much until after the career of Alexander the Great. The land they migrated into was called Parthava by the Persians and Parthia by the Greeks, so we call them the Parthians after this.

Arsaces fell in battle around 248 B.C., living just long enough to give his name to the dynasty that would rule afterwards. His brother, Tiridates, ruled for the next thirty-seven years, and his actions ensured the new kingdom's survival. Early in his reign he ruled from the mountains of Turkmenistan, but soon he built a new capital, named it Asaak or Arsak (after Arsaces) and crowned himself king there. Perhaps because of their nomad heritage, the Parthians were always a restless lot, moving their capital more than once. Later Tiridates would move his court again, to the Greek city of Hecatompylos. His successors would also rule from Ecbatana, the ancient capital of Media, and finally from Ctesiphon(12), their name for ancient Opis (see footnote #4).

Gradually the Parthians became civilized, but not enough to lose their martial skills; up to the end of their history they had an army made up mostly of archers on horseback. They were particularly famous for one skill; they trained themselves to shoot at targets behind them with nearly as much accuracy as when they aimed at something in front (the Romans regarded them as dirty fighters for this!). The tactic of shooting backward arrows became known as the "Parthian shot"; modern English shortened it to "parting shot."

The Seleucids were initially preoccupied with troubles in the west; it wasn't until 232 or 231 B.C. that Seleucus II arrived in the east with an army to put down the rebellion. When it arrived, Tiridates sensed that his enemy had a superior force and retreated to his native steppe. Seleucus pursued as far as the Jaxartes (Syr Dar'ya) River, but then turned back when he received alarming news from Syria. Tiridates was thus able to re-occupy the district both he and Seleucus had abandoned and shortly after that he annexed Hyrcania, on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea.

The next king, Artabanus I (211-191), had the bad luck of living at the same time as Antiochus the Great. Artabanus was defeated, lost half his kingdom to the Greeks, and had to recognize Seleucid overlordship to keep his throne. His successor, Priapathius (191-176), recovered Hyrcania, taking advantage of the defeat inflicted upon Antiochus by the Romans. As the Parthians advanced west, the nearest Seleucid provinces, Elymais (Elam) and Persia, revolted and looked to the Parthians for assistance. Priapathius was followed by Phraates I (176-171), who broke tribal tradition. Instead of giving the throne to one of his many sons, he bequeathed it to his brother Mithradates I. His choice was no mistake.

The Revolt of the Maccabees

The anti-Semitism of Antiochus Epiphanes was intolerable to Mattathias, an aged priest with five sons. When a Greek general came to Modi'in, the hometown of Mattathias, and ordered him to sacrifice to Zeus, he refused, but a frightened Jew agreed to do it. Mattathias killed the Jew and the general, tore down the altar, and shouted to everyone else: "Let everybody who is zealous for the Law and stands by the agreement [God's covenant with the Jews] come out after me." Then he fled into the hills with 1,000 new followers and began a guerrilla war against the Greek army. He died a year later (166), and leadership passed to his third son, Judas Maccabeus. Before this time Judas and his family went by the name of Hasmoneans, but after this they called themselves Maccabees, from the Aramaic word makkabah, meaning "hammer."

Antiochus did not take this band of faithful Jews seriously. He went east to fight the Parthians in Iran and died before he could come back, leaving only small detachments to deal with the Jews. Even so, the Greek forces were larger, better equipped, and better trained than their Jewish opponents. What Judas had in his favor, however, was faith that God would deliver His chosen people. This caused the impossible to happen when Judas defeated the Greeks three times and liberated Jerusalem in 165 B.C. He cleansed the Temple and reestablished the rites which Antiochus had suspended. The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah still commemorates this event today.

The death of Antiochus started a contest for the Seleucid throne. Lysias, the general who had been in charge of the campaign against the Maccabees, headed home to Syria to support his favorite candidate, Antiochus V. Since he could not be in two places at once, Lysias offered full religious liberty to the Jews if they submitted to Seleucid authority. This did not resolve the conflict, though, because soon after that both Antiochus and Lysias were executed by a rival to the throne, Demetrius I. Then Demetrius showed what he thought of the Jews by reinstating Alcimus, a high priest the Jews hated because he favored Hellenism. Alcimus was so unpopular that they ran him out of town. Another Greek army came down from Syria in support of Alcimus; at Elasa, north of Jerusalem, Judas died in battle (160).

Jonathan, the youngest brother of Judas, became the new commander of the Maccabean forces, and found the political situation in his favor. Rome and Sparta made treaties of alliance. Jonathan had to continue the war with the Seleucids at first, until Demetrius I was killed in battle (150) by a usurper named Alexander Balas, who claimed to be a son of Antiochus Epiphanes. Many people in Antioch, however, did not accept the new king, and they offered the crown to Egypt's Ptolemy VI. Ptolemy declined in favor of the legitimate heir, Demetrius II. In 145 B.C. fighting broke out between Alexander and Demetrius, and Ptolemy came to support Demetrius. He took Antioch and killed Alexander in a battle along the Oenoparus river (in northeastern Syria) but was mortally wounded and died soon afterward.

Both Alexander I and Demetrius II needed all the friends they could get, so they gave the Maccabees favorable terms of peace. Jonathan was named civil and military governor of Judaea; he was murdered, however, by Trypho, yet another pretender to the Seleucid throne, who captured him at Ptolemais (Acre) in 142 B.C.

The last living son of Mattathias, Simon, took up the work of his slain brother Jonathan. Demetrius II, in return for Jewish assistance in putting down the rebellion of Trypho, renounced all claim to tribute and gave the Jews full independence. Simon was made both hereditary high priest and king, but his eight-year reign ended in tragedy. After defeating Antiochus VII, a later Seleucid king who attempted to gain control over Judaea, Simon was assassinated by his son-in-law Ptolemy, who hoped to gain the throne for himself. Ptolemy was in turn defeated by the son of Simon, John Hyrcanus I. He became the next king, and took Israel in new directions, both materially and spiritually. We will come back to the Maccabees later in this chapter, but now it is time to go east and cover the best years of the Parthians.

Parthia: The Philhellenic Period

Mithradates I (171-138, also spelled Mithridates) was such an outstanding ruler that we now regard him as the real founder of the Parthian Empire. Early in his career he faced an invasion from Antiochus Epiphanes, which ended with the Greek king's death at Tabae (modern Isfahan?). Mithradates always had the initiative after that. In twenty years of campaigning, he conquered all of Iran and Iraq (160-140). One of the latter Seleucid kings, Demetrius II, hastily gathered an army and marched east. To his amazement, he was outmaneuvered, defeated, captured, and paraded on a leash through the cities he once ruled. Yet Mithradates, like the great Persian king Cyrus, preferred kindness to cruelty, and went out of his way to win the friendship of new subjects. He made Demetrius governor of Hyrcania and gave him a daughter for a wife. To the Medes and Persians he portrayed himself as the restorer of the old Achaemenid empire, calling himself the "Great King." To show his goodwill to the Greeks he had coins stamped with the nickname "Philhellene."

Seleucia, the commercial center of Iraq, saw even better days under the Parthians than it did under the Seleucids; in the first century A.D. its population peaked at a stupendous 600,000 inhabitants. The Parthians, still preferring the rural life, left their Greek citizens alone; the Greeks even continued to stamp coins with dates counting from the beginning of the reign of Seleucus I (312 B.C.). Outside Seleucia the Parthians built a military camp on the opposite side of the Tigris; this became the future city of Ctesiphon.

Mithradates spent his last three years dealing with a problem on his eastern frontier. In Mongolia the Huns defeated and chased away a neighboring tribe, which the Greeks called the Tocharians and the Chinese called the Yuezhi. This caused a chain reaction of events that went on until it reached the Parthians: the Tocharians moved west into Central Asia; the Scythians were in turn dislodged by the Tocharians; the Scythians began to raid Parthian and Bactrian territory (they overthrew the Bactrian kingdom around 130 B.C.). The next Parthian king, Phraates II (138-128), faced challenges from both the west and the east. He treated the royal prisoner, Demetrius II, just as well as Mithradates had, possibly to make him a future puppet monarch in Syria. Demetrius responded by making repeated attempts to escape. Still, his ever-watchful Parthian captors ran him down each time, and once Phraates gave him a pair of golden dice for a present--a gentle warning to stop gambling with his life.

A final attempt to recover the lands east of the Euphrates was made by the brother of Demetrius, Antiochus VII. His superbly trained troops defeated the Parthians three times, and chased them all the way to Media. With the onset of winter, the Greek army stayed in Iran, occupying several key cities and harshly oppressing the population. In the spring of 129 B.C., Antiochus put forward his terms for peace: the Parthians must release Demetrius, evacuate all of Iran except Parthia, and pay tribute. Parthian agents started a rebellion in the occupied areas, and Phraates launched a surprise attack on Antiochus. They slew the Seleucid king, captured most of his troops and drafted them into the Parthian army. Demetrius had his throne handed back to him on a silver platter, and he ruled Syria for the last four years of his life. But the Parthians did not let him have the areas which had revolted with their encouragement; those became two client kingdoms: Adiabene on the upper Tigris (ancient Assyria under a new name), and Charax (also called Mesene), a small Arab-ruled kingdom in southern Iraq and Kuwait. The eastern territories of the Seleucid kingdom had been lost for good; the frontier of western civilization was pushed back to the Euphrates.

However, the Parthians did not march into Syria, because a new wave of raids from the Scythians(13) had broken into Iran. Phraates went to meet them in battle, using the Seleucid Greeks he had captured in the defeat of Antiochus. When the fighting started to go badly for Phraates, the Greeks immediately turned on him, helping the nomads slaughter both Phraates and the Parthian army. It was a lesson the Parthians would long remember.

The uncle and successor of Phraates, Artabanus II (128-123), also fell victim to the nomads. The next king, however, was Mithradates II (123-87), the greatest of all Parthian rulers. Earlier we compared Mithradates I with Cyrus, because both were great empire-builders; in the same fashion we can compare Mithradates II with Darius I, because both of them made the country rich. Before this time, the Parthians, like the Persians before them, found themselves in a barren land where they had to make the most of what they had. Despite this, they did succeed in making Iran liveable, thanks to an advanced irrigation system. To prevent evaporation in the dry heat, they built qanats, or underground tunnels, to carry water for miles; many qanats are still used in Iran today. They were also able to raise fruits, vegetables, rice, and other grains in the Tigris and Euphrates valleys.

It was as middlemen that the Parthians found their way to true riches. In 128 B.C., a Chinese ambassador followed the Yuezhi across Central Asia; when he found them he also discovered Parthia and India. The Chinese were amazed to learn that they were not the only civilized nation on earth! Thirteen years later, Mithradates and the Chinese emperor, Wu Di, exchanged embassies. Both sides were greatly interested in each other's products. The Chinese wanted grapes and the superior Arabian horses of the West, while Chinese silk found ready customers everywhere it was exported, since nobody else could make a cloth as fine as that. The result was the famous Silk Road, which went across Central Asia, carrying trade goods on camel caravans for thousands of miles. Besides the silks and horses mentioned, caravans moved dried fruits, olive oil, salt, perfumes, statues, precious metals, gems, rugs and spices. A few years later, the Romans noticed that the Parthian fashion was switching from leather to silk, and they wanted silk, too, so they got involved in the trade. The Romans and Chinese did not meet face to face, and the Parthians took a cut of everything that passed through their territory, to the dismay of the traders on both ends of the route. Later, both Roman and Chinese military expeditions attempted to eliminate the middlemen, but the attacks occurred at different times, allowing the Parthians to meet each challenge when they were ready for it.

On the western frontiers, Mithradates put down rebellions by the governors of Iraq and Charax and installed Tigranes (95-56) as the vassal king of Armenia; another Seleucid king, Demetrius III, was taken prisoner. In the east, he managed to divert the Saka raiders into India. The nearest Sakas, the Surens or Indo-Parthians, became a client kingdom in southeastern Iran and Pakistan; the rest formed other friendly states in India. The Parthian empire was always a loosely organized, feudal state, and near the borders the kings always chose to govern via native satellite rulers, rather than run those lands directly.

The Empire of Mithradates II.

Mithradates never forgot the treachery of the Greek mercenaries, and improved the army so that he would no longer need their services. The cavalry remained the main arm of the army, but he also required the great landowners to supply peasants for infantry units, which were summoned in time of need for garrison duty and missions in rough country. Since the cavalry was roughly equal to the Central Asian nomads in equipment and ability, he added knights--a heavy cavalry of shock troops, men armed with lances and wearing chainmail for armor, mounted on the largest horses available. He may have gotten the idea for this from the Sarmatians, a tribe in Russia that used lances and chainmail already. The new army was expensive(14), had a provincial attitude, and was not as well trained as the Greeks it replaced, but at least it was Parthian.

The Romans came to know the Parthians and their tactics better than they might have wished. In 92 B.C., the Roman general Sulla advanced to the Euphrates River, and Mithradates sent him an ambassador to offer friendship. Sulla arrogantly took this overture as submission; he had no idea that the military and economic power he was facing was almost equal to his own. They reached an agreement concerning Armenia, but the ambassador was treated in such a humiliating and cavalier manner that Mithradates later executed him for failing to uphold the honor of Parthia. Seven hundred years of bad east-west relations followed because of the misunderstanding at the first Roman-Parthian contact.

The Kingdom of the Holy Warriors

John Hyrcanus I (134-104) had to fight to keep the crown of the Maccabees, first by defeating his rival Ptolemy. Then Antiochus VII attacked him, besieging Jerusalem. Hyrcanus bought off the Greeks by agreeing to their demands: tear down the towers on the walls of Jerusalem and pay a tribute of 3,000 talents. When the money in the treasury ran out, Hyrcanus opened the tomb of King David and took out what he needed; because of this action, the Maccabees were never again as popular as they used to be.

John Hyrcanus refused to admit defeat. He asked the Romans for aid should the Seleucids attack again. By this time Rome had finally vanquished its old archenemy, Carthage, so they gave aid generously. He also built up a professional Jewish army to make Judaea a powerful sovereign state. Fortunately for him, the Seleucid kingdom had degenerated to the point that Jewish independence was no longer an issue. With the Seleucid threat gone, Hyrcanus could expand the kingdom's boundaries beyond Judaea. He conquered Idumaea(15) and Samaria, and converted their inhabitants to Judaism by force; the Samaritan temple on Mt. Gerizim was destroyed(16).

Though he was an effective ruler, the worldly policies of John Hyrcanus offended the pious of Israel. Because of this he broke with the party of the Pharisees, the spiritual descendants of the righteous who had stood against Seleucid tyranny in the days of Antiochus Epiphanes. He joined with the Sadducees, the party that did not think Hellenism was so bad.

The son of Hyrcanus, Aristobulus I, reigned for one year, just long enough to conquer the Galilee region. Aristobulus was succeeded by his brother, who also had a Greek name, Alexander Jannaeus (103-76). Jannaeus annexed the plain of Sharon, Moab, and Gilead, bringing the kingdom to its greatest size. At home, however, things went from bad to worse. The disagreement between Pharisee and Sadducee became so violent that they plunged the nation into civil war. Before it was all over Egypt's Ptolemy IX tried to take Gaza; the Nabataeans (Arabs) raided the country; the Pharisees even requested help from a Seleucid king, Demetrius III. All this time Jannaeus tried to impose Hellenism on the people because the Sadducees supported it and the Pharisees opposed it (Oh, how the Maccabees have changed in the 80 years since they got started!). After six years of fighting, Jannaeus came out victorious; at his victory celebration he crucified 800 captive rebels and slaughtered their wives and children before their pain-numbed eyes.

Another Mithradates the Great

The decline of the Seleucid Kingdom left a power vaccuum in the eastern Mediterranean. No local state had a navy strong enough to fill it, and the the greatest nation in the western Mediterranean, the Roman Republic, wasn't very interested in Asia while Carthage was a threat closer to home. In that lawless environment, a group of buccaneers, the Cilician pirates, took over, and from their base at Coracesium (modern Alanya), on Asia Minor's southern coast, they terrorized all shores east of Italy. Their favorite targets were grain ships, and the prisoners they captured in their raids were either held for ransom or sold as slaves on Delos, whichever brought a bigger profit.

With the end of the Punic Wars, Rome became supreme in the west. Now some Asians came to regard further Roman expansion as inevitable. One of them was the eccentric last king of Pergamun, Attalus III Philometor Euergetes. In his will he bequeathed the kingdom to Rome, so upon his death in 133 B.C. Pergamun became the Roman province of Asia. Thirty years later, Rome sent a fleet to deal with the Cilician pirates, but the Roman plantations (latifundia) needed slave labor too much, so instead of getting rid of the pirates completely, the fleet commander, Marcus Antonius, stopped after conquering the western half of Cilicia (104-102 B.C.).(17) By the end of the century Egypt, Bithynia, Cappadocia, Galatia and Paphlagonia (a small buffer state between Bithynia and Pontus) were all official Roman protectorates. But one Middle Eastern leader, Mithradates VI of Pontus (no relation to the Parthian kings by the same name), saw the Romans differently, as an obstacle to overcome on his path to greatness.

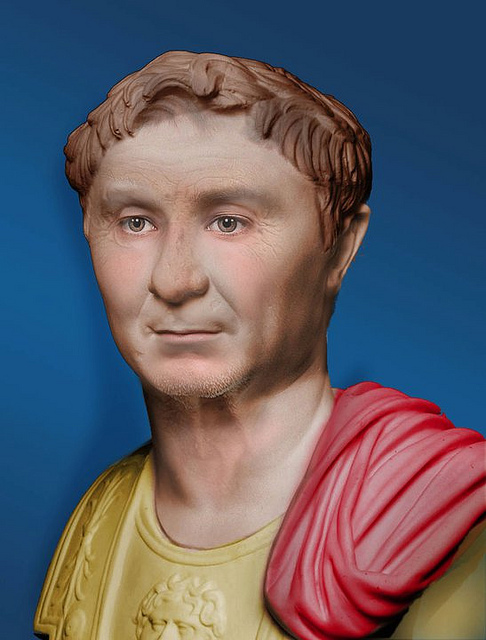

Mithradates VI.

Mithradates was only twelve years old when he inherited the Pontic throne in 120 B.C. After he grew up, however, he was a brilliant organizer, always picking the right man to do any job. In the last decade of the second century he enlarged the kingdom by taking Colchis (Georgia) and the Crimea, turning the Black Sea into his personal lake. In the east he made alliances with Parthia and Armenia, giving his daughter in marriage to Armenia's King Tigranes. His moves to take the pro-Roman states of Asia Minor were thwarted by Rome, though, and an attempt to depose the pro-Roman Nicomedes III of Bithynia failed. Raids on Pontic territory by Nicomedes in 88 B.C. led to the First Mithradatic War (88-84). At this point the Romans were preoccupied with the troubles that marked the end of the Roman Republic, giving Mithradates a fabulous opportunity. Before the year was over, he overran all of Asia Minor, massacred a reported 80,000 Italian colonists, and even invaded Greece. However, in Greece he confronted the overdue Roman response. Rome's man of the hour, General Lucius Cornelius Sulla, recovered Greece, while another army led by Gaius Flavius Fimbria chased Mithradates back to Pontus. The war in Italy was not over yet, though, and because he was in a hurry to get back and finish it, Sulla dictated lenient terms for peace: Mithradates got to keep Pontus, Colchis, and the Crimea, though he did pay an indemnity.

Tigranes the Great

Antiochus VII was the last strong king the Seleucids had. After him the only land left to the incredible shrinking empire was Syria. And his many successors could not even hold onto that; the cities of Tyre and Sidon broke away to enjoy a last fling at independence before the Romans arrived, while the area around Damascus became the Arab Ituraean kingdom. For a generation the dominant figure in Seleucid politics was a woman, Queen Cleopatra Theos (not the Cleopatra you're thinking of--that was Cleopatra VII). The daughter of Egypt's Ptolemy VI, she gave legitimacy to three Seleucid monarchs (Alexander I, Demetrius II, and Antiochus VII) by marrying each of them as he ascended the throne in Antioch. She also showed enough independence to mint her own coins, stamped with her portrait and the title Thea Eueterias(18). After Cleopatra died in 121 B.C. the struggles for the crown became constant; between 96 and 83 B.C. there were six contenders fighting simultaneously!

Though the Parthians had helped to bring down their western neighbor, first the Sakas and then a series of weak kings after Mithradates II kept them from taking advantage of the final Seleucid collapse. Instead the easy pickings went to Tigranes, who revoked the Parthian overlordship imposed upon him at his coronation, relieved his late masters of Atropatene and Adiabene, and added insult to injury by taking on the Persian title "King of Kings." Then he moved west to seize Cilicia and most of Syria (83). The Syrians welcomed him for ending the Seleucid squabble, though he left the cities of Antioch and Acre for the last Seleucid princes to pretend being kings in. For the next seventeen years Armenia (yes, Armenia!) was the dominant power in the Middle East.

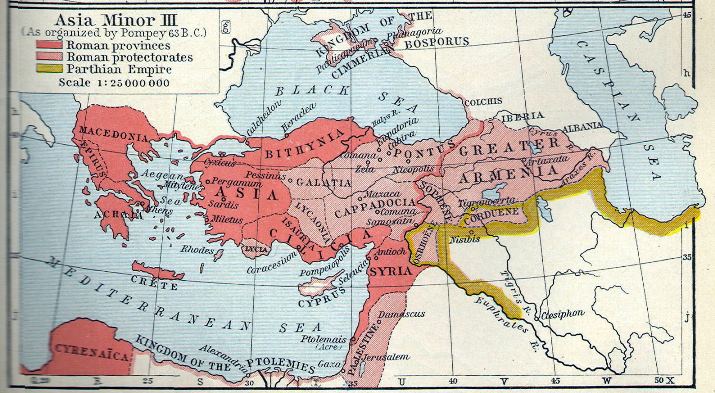

Rome Takes Over

The Second Mithradatic War (83-81) began when an ambitious Roman general named Lucius Licinius Murena invaded Pontus; he was defeated. Then in 74 B.C. the Romans sent a second fleet against the Cilician pirates, under another Marcus Antonius, son of the first Marcus Antonius and father of Mark Antony, the future rival of Octavian. He failed, too; when he went after the pirates' winter base on Crete, he was defeated, and spent his last days in a pirate prison. Also in 74 B.C., Nicomedes III of Bithynia followed Pergamun's example and willed his kingdom to Rome. Opposing this action, Mithradates VI invaded Bithynia, and so won the first round of the Third Mithradatic War (73-65).

The Roman commander, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, threw Mithradates out, and the Pontic king fled to the court of his ally Tigranes. Lucullus then invaded Armenia, capturing its rich capital city, Tigranocerta, in 69 B.C. He attempted to subjugate the Armenian countryside during the following year but was unprepared for the mountains and the inhospitable climate. After months of slow going, he finally inflicted a defeat upon the anti-Roman coalition (the battle of Artaxata). At this point Lucullus was near the new Armenian capital but his exhausted troops refused to go any farther and forced a retreat to the Euphrates valley. Mithradates returned to Pontus to prepare another offensive, while Rome recalled Lucullus and replaced him with Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, known to us as Pompey the Great.(19)

Pompey.

In contrast to Lucullus, Pompey's victories were quick and conclusive. In 67 B.C., Pompey was made a temporary dictator and sent east with twenty legions, five hundred ships, and all the money he needed, to finish off the Cilician pirates. Since we last saw them, the pirates had allied themselves with Mithradates against the Romans, and now were threatening Rome's grain supply from Africa. Not only did Pompey succeed where his prececessors failed, he did it in three months, by offering amnesty to those who were willing to become farmers, before using his fleet to destroy the rest. Next, he utterly defeated Mithradates at the battle of Lycus (66), forcing him to hide in caves and flee to the Crimea. Mithradates dreamed up a plan to invade Italy from the north Hannibal-style, but his troops deserted to his son Pharnaces, and he committed suicide instead(20). Pompey had Mithradates buried in the rock-cut tombs of his ancestors at Amasia, the capital of Pontus. Then Pompey went after Tigranes, who was likewise undone by a disloyal son. Tigranes kept his throne, but he lost most of his territory, paid a large indemnity, and ruled after that as a client king of Rome. The hastily built Armenian Empire did not survive its first major test.

Once the fighting was over Pompey made the direct settlement of eastern affairs that the Senate had been avoiding for over a century (64). Eastern Cilicia and part of Pontus were annexed; the other states of Asia Minor and Armenia had their status confirmed as Roman vassals. Then he turned Syria into a Roman province, finishing off the Seleucid kingdom.

Meanwhile in the Maccabean kingdom, peace returned under Salome Alexandra, the wife of Alexander Jannaeus, who took control of the government after his death. Her eldest son John Hyrcanus II served as high priest. Because both of them were friendly to the Pharisees, there was little civil strife, and the system worked during the nine-year reign of Alexandra (76-67). Upon her death a power struggle immediately erupted between Hyrcanus and his younger brother, Aristobulus II, whom the Sadducees backed. Aristobulus won the first round, but Hyrcanus was persuaded by Antipater, a wealthy Idumaean friend, to flee to Petra, the capital of the Nabataeans. Hyrcanus was promised aid by Aretas, the Arab king, and they returned with an army to besiege Jerusalem.

The Maccabean civil war ended when the Romans got involved as a third party. When Pompey arrived in Syria, both Aristobulus and Hyrcanus sent gifts, each hoping to persuade him to support his side. Pompey decided that Aristobulus was untrustworthy and ordered the siege of Jerusalem, taking the holy city in 63 B.C. Claiming the spoils of a conqueror, Pompey marched into the innermost room of the Temple, the "Holy of Holies," where only priests were permitted; he found the room empty. This immediately turned many Jews against Pompey, and a few years later they supported his rival, Julius Caesar, because of this act. Although John Hyrcanus II remained the official ruler of Jerusalem, Antipater was the power behind his throne; meanwhile the Romans were the real masters over both Hasmonean and Idumaean, and they would rule the Holy Land for the entire period covered in the next two chapters.

This is the End of Chapter 6.

FOOTNOTES

1. The behavior of Alexander initially embarrassed many Greeks; they did not support him wholeheartedly until 331 B.C.