| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Concise History of India

Chapter 4: RECENT SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY

This chapter covers the following topics:

The Road to Independence

When the Indian nationalists of the nineteenth century passed from the scene, one of the twentieth century's most remarkable figures took up leadership of the movement. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) started as a law student in London, but success eluded him in his own country, so he went to practice law in South Africa in 1893. There he immediately ran into the racial discrimination that we would later know as apartheid, causing him to develop the philosophy that governed the rest of his life.

Whereas the previous Indian nationalists had expressed their views in ways that appealed to well-educated Indians, Gandhi gave Indian nationalism a new dimension by introducing the involvement of the masses. Drawing upon a variety of sources--the main ones being Hinduism, Christianity, and the works of Leo Tolstoy--he believed that the three most important virtues were truth, nonviolence, and self-discipline. He belonged to the Vaishya or merchant caste, but he lived an ascetic's life with almost no personal possessions so rich and poor alike would hear his message. He called his campaign Satyagraha (nonviolent non-cooperation), and it involved resisting the British in any way which did not involve violence: boycotts, civil disobedience, general strikes, hunger strikes, making homespun clothing (as opposed to buying the textiles of British factories), and even making salt from sea water (to resist the salt tax). In 1915 Gandhi returned to India and was hailed as a Mahatma (great soul or saint). He set up an ashram (retreat), gathered and trained his truth fighters, and received subsidies from wealthy contributors who sympathized with his cause.(1)

At first Gandhi was willing to cooperate with the British, and a promise of postwar concessions was enough to guarantee Indian support of the Allied cause during World War I. However, the legislation passed after the war was far less than had been hoped for. Gandhi declared March 30, 1919 a day of national humiliation, during which all work would cease and the entire population would pray and fast. After that protests increased, occasionally turning to violence. On April 13, a British platoon surrounded and fired into a crowd of 10,000 demonstrators in Amritsar. In ten minutes the soldiers fired 1,650 rounds of ammunition, of which very little was wasted: 379 people were killed and 1,208 wounded. After the massacre Gandhi declared, "Cooperation in any shape or form with this satanic government is sinful." The popular support for Gandhi's campaign was so enthusiastic that it persuaded the British to grant one concession after another afterwards.

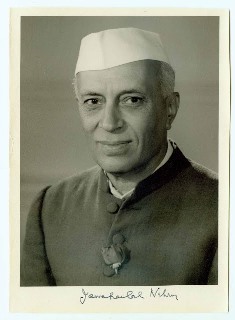

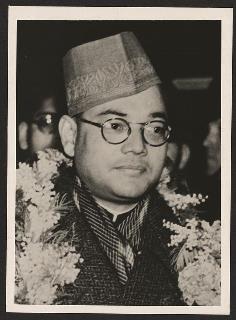

From left to right: Mohandas K. Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Subhas Chandra Bose. From Old Indian Photos.

A few words on two other leaders in the Indian nationalist movement would be appropriate here. Leadership of the Indian National Congress alternated between Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose. Nehru (1889-1964) was an agnostic member of the Brahman caste and the son of a previous Congress leader. While he was attending college in England, the noble families of Britain entertained Nehru, but when he got back to India he was snubbed by white middle-class colonials. He met Gandhi in 1916 and the two men, despite their different backgrounds, became the best of friends. Motivated by Gandhi's emphasis on action rather than words to combat injustice, Nehru was soon thrown in jail for demonstrating; in his cell he studied Karl Marx and added socialism to his philosophy. His political education was completed one night in 1919 as he traveled on the same train as General Reginald Dyer, the leader of the troops at the Amritsar massacre. From the next sleeping compartment, Nehru overheard Dyer telling other officers that he had wanted to make the Sikh holy city "a heap of ashes" and had only held back because he "took pity on it." Nehru was deeply shocked both by this admission and by the general British approval of Dyer's action. "I realized then," Nehru later wrote, "how brutal and immoral imperialism was and how it had eaten into the souls of the British upper classes."

Subhas Chandra Bose (1897-1945) was the son of a radical judge from Bengal. He was every bit as extreme as his predecessor Tilak; his favorite slogan was "Give me blood and I promise you freedom!" Unlike the other nationalists, who agreed to support Britain in World War II if there was progress toward independence, Bose openly supported the Axis dictators. Early in 1941, he escaped house arrest in Calcutta and made his way via Afghanistan and Russia to Germany, where he met Adolf Hitler, married a German and started broadcasting Nazi propaganda. He recruited 2,000 Indian prisoners of war (taken in North Africa) to form an army unit called the German Indian Legion; in Southeast Asia he formed a larger force called the Indian National Army for the Japanese. In March 1942 the Japanese occupied the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and later put them under an Indian government led by Bose, but during the one time Bose visited the islands, the Japanese kept him isolated from the native population, so he never was anything but a puppet ruler and probably did not know how brutal the Japanese force was. Then when the Japanese invaded India in early 1944, the Indian National Army went with them, advancing about 150 miles before it was defeated and forced back into Burma. The British pursued and retook Rangoon in 1945; Bose fled to Tokyo and was killed in a plane crash on Taiwan.(2)

In 1935 India was given a federal government and a measure of self-rule; that left the questions of when independence would come and what form it would take. The second question was very important. Nepal and the predominantly Buddhist areas (Bhutan, Sikkim and Sri Lanka) were made into separate states without any protests.(3) The subcontinent's Moslem community, however, was a more difficult matter. The Hindu-Moslem unity which the British had worked hard to achieve was coming apart, as the Indian National Congress and the Moslem League alienated themselves from each other. Mohammed Ali Jinnah (1876-1948), the leader of the Moslem League, called for the creation of a separate state for India's Moslems. The name he invented for it was an acronym for most of the provinces it would one day contain: P for Punjab, A for the Afghans in the Northwest Frontier region, K for Kashmir, S for Sind and "TAN" for the last syllable in Baluchistan. Throw in an "I" to make the whole thing easier to pronounce, and the result was Pakistan, which also means "Land of the Pure." While proposals for Pakistan's status and borders changed constantly, the creation of it became the primary goal of the Moslem League from 1940 onward. As Gandhi and the Congress campaigned under the slogan "Quit India!," the Moslem League told the British to "Divide and Quit!"

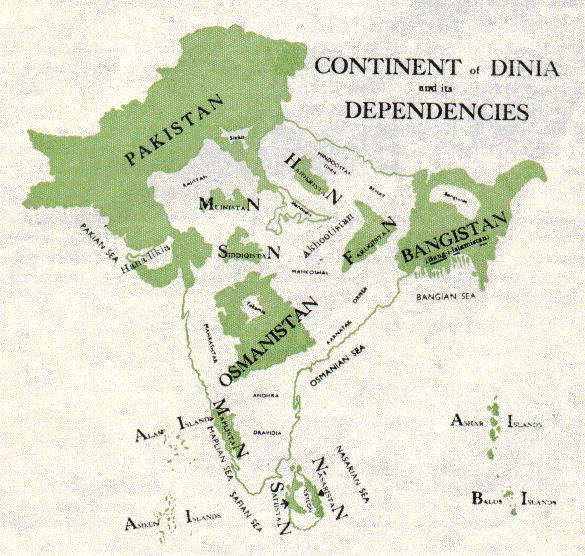

An early proposal (from the 1930s) showing the territories that could become part of Pakistan. Suggested by Choudhry Rahmat Ali (1895-1951), a colleague of Jinnah, it included not only present-day Pakistan but also most of the land in the east, all of Kashmir, most of the Indian Ocean islands, and the states of the Moslem maharajahs. Compare this with the next map, which shows what the Moslem League actually got. From Wikimedia Commons.

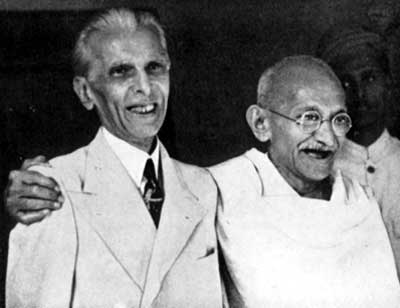

Jinnah and Gandhi enjoy a happy moment in September 1944, before politics drove them apart.

On the Pakistan issue, Jinnah became absolutely inflexible. At one point Gandhi even offered Jinnah leadership of the whole subcontinent if that would keep him from dividing India, but Jinnah refused, saying that the Indian people would no longer accept such a compromise. What was not known at the time was that Jinnah had a case of tuberculosis so bad that it killed him a year after independence; he kept it secret because the British would not have given him what he wanted had they known!

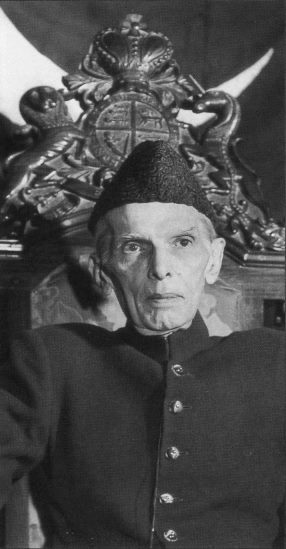

Mohammed Ali Jinnah, showing the ravages of tuberculosis.

In 1942, as the Japanese advanced to the eastern border of India, the British government reached a political settlement with the Moslem League, but not with the Congress. Fearing mass civil disobedience, the government arrested Gandhi, Nehru, and the other Congress leaders. They were released again in 1944 and negotiations resumed. June 1948 was picked as the date for independence.

The last viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, arrived in February 1947 promising independence within 16 months, but the rioting between Hindus and Moslems had gotten so bad that he granted it in six. On August 15, 1947, India and Pakistan became independent nations. Because there were Hindus and Moslems in every community on the subcontinent, there was no way to partition India and Pakistan without leaving millions of people on the wrong side of the border.(4) Soon the roads became clogged with 8.8 million Hindu and Sikh refugees fleeing to India and 8.5 million Moslem refugees fleeing to Pakistan. Tragically, no attempt was made to protect these refugees, and violence spread like wildfire. Fights often broke out when groups of refugees heading in opposite directions happened to meet. Trains crossing the border were frequently attacked and arrived at their destination with all of their passengers dead. In the cities minority communities were massacred. British troops were too busy packing their bags and getting out to restore order, and native troops either looked the other way or took part in the killing. More than one million people died in 1947-48 because of the partition.

Mahatma Gandhi never gave up trying to reconcile Hindus and Moslems. From Calcutta he stopped the violence with a hunger strike, threatening to fast unto death unless peace returned. The fighting stopped in five days. Moslems feared that if he died, they would suffer a new and even more terrible bloodbath at the hands of the Hindus, while Hindus did not want to be guilty of causing his death. Gandhi broke his fast and predicted that he would live to be 125. He only lived two weeks after that, though; when he announced he was going to Pakistan on a goodwill mission, a Hindu extremist assassinated him. The twentieth century's most devoted peace demonstrator became the last victim of the violence that India's partition produced.

India Under the Nehru Dynasty

The Indian constitution, finished in 1950, is the longest of any nation; at 395 articles and 250 pages, only the constitution of the European Union is longer. It created a government modeled after British and American political institutions, for a nation whose demographics are far more complex. Jawaharlal Nehru became India's first prime minister. His family held that office for thirty-seven of the first forty-two years after independence, which helped maintain stability. Nehru found himself facing some formidable tasks: bring peace and prosperity to a land the British had left in a sorry state, and set the precedents that future leaders of the world's most populous democracy would follow. One of Nehru's precedents was a neutral foreign policy. With the Cold War at its height during his administration, Nehru was not willing to align India with either the United States or the Soviet Union. Instead he proclaimed himself as the champion of all oppressed peoples in Africa and Asia, denouncing imperialism (especially Western imperialism), and advocating nuclear disarmament and self-determination (except in Kashmir). As a panacea for the world's woes, he set forth five principles called the Panch Shila(5); he applied them in an agreement with China concerning Tibet in 1954, and at the first international conference of nonaligned nations (held in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955). In 1956 India absorbed the last French outposts on the coast; five years later it annexed the Portuguese enclaves as well.

A summit meeting of nonaligned leaders. From left to right: India's Jawaharlal Nehru, Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah, Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser, Indonesia's Sukarno, Yugoslavia's Josip Broz Tito.

Another problem that the British left for Nehru was the maharajahs; what was to be done with 562 princes of every personality type imaginable, ruling personal estates ranging in size from a few acres to realms larger than many European countries? There was no place for these petty monarchs in the governments of either India or Pakistan, and in the end both nations decided to buy them out: in return for giving up his land, each maharajah was offered a sizeable pension for life. Most of them agreed to this plan, but three caused trouble. Two of them, the Nawab of Junagadh (in Gujarat) and the Nizam of Hyderabad, were Moslems surrounded by Hindus on every side, and they were determined to keep their lands from becoming part of India. The Nawab fled to Pakistan when his people voted overwhelmingly to join India; it took an outright invasion of Hyderabad by the Indian army before the Nizam saw the light and gave up his sizeable state in the Deccan.

Kashmir presented the opposite problem: its population was 85% Moslem, but the maharajah was a Sikh. When he refused to join Kashmir with Pakistan, guerrilla violence by Moslem rebels began. Pakistan gave support to the rebels, India aided the Kashmir government, and in October 1947 the escalating violence drew both nations into a war over Kashmir. It ended on January 1, 1949, when a UN-meditated ceasefire divided Kashmir so that Pakistan got one third of it, and India got the rest.

Kashmir, a dangerously disputed territory. Click on the above thumbnail for a full-sized map (274 KB, opens in a separate tab).

The Indian-controlled part of Kashmir included an ancient mountaintop kingdom called Ladakh. The Chinese had claimed eastern Ladakh, the desolate Aksai Chin plateau, as far back as the 1890s, but with all the troubles China suffered in the first half of the twentieth century, they never go around to doing anything with Aksai Chin, so the border the British drew, giving the land to India, was the one allowed to stand. Those troubles ended when China became communist in 1949, and in 1957 the Chinese occupied Aksai Chin, so that a road could be built between the Chinese provinces of Xinjiang and Tibet. This area is so remote that the Indian border patrols did not know they had lost control of it until they discovered the nearly-completed road a year later! China also disputed India's border territory east of Bhutan, called the North-East Frontier Agency or Arunchal Pradesh. Those disputes, coupled with India giving shelter to the Dalai Lama and other refugees after China suppressed a Tibetan rebellion in 1959, led to the month-long Sino-Indian War in 1962. China launched two attacks, more than a thousand miles apart; one drove Indian troops out of Aksai Chin, while the other overran the North-East Frontier Agency. The Chinese stopped advancing once they held all of the land they claimed, allowing a cease-fire. The cease-fire line has not moved since 1962, and the only fighting between Indians and Chinese since then occurred in two shooting incidents, both in the protectorate of Sikkim in 1967; therefore it's safe to assume that the cease-fire line has become the permanent frontier. India reported 1,383 killed, and China reported 722 deaths; because the fighting took place at elevations two to three miles above sea level, most of the casualties were caused by the thin air and extremely cold weather.

Though China was technically the winner, most of the outside world saw it as the aggressor, causing China to suffer in diplomatic relations. Because the war ended so quickly, those nations that sympathized with India could not send military aid in time. Both the Soviet Union and the United States were among those taking India's side in the dispute, but the Cuban Missile Crisis at the same time kept the two superpowers from getting involved. India thought positively of the Soviets for that, and cultivated good relations with the USSR for the rest of the 1960s and 70s. Likewise, Pakistan improved relations with China and the United States, to offset anything that Indo-Soviet cooperation might produce.

Nehru died in 1964, and his successor, Lal Bahadur Shastri, lasted less than two years. The main event of Shastri's administration was a rematch with Pakistan over Kashmir. In 1965 thousands of Pakistani troops infiltrated Indian-controlled Kashmir, with the intention of launching an uprising, and India responded by attacking all along the Indo-Pakistani frontier. This war saw Indian and Pakistani warplanes clash for the first time, and the largest tank battles since World War II. Like the 1947-49 war, it was inconclusive, and both sides agreed to another cease-fire after the United States and the Soviet Union put pressure on them to negotiate. The cease-fire agreement was signed in Tashkent, Uzbekistan on January 10, 1966, and one day later, Shastri died.

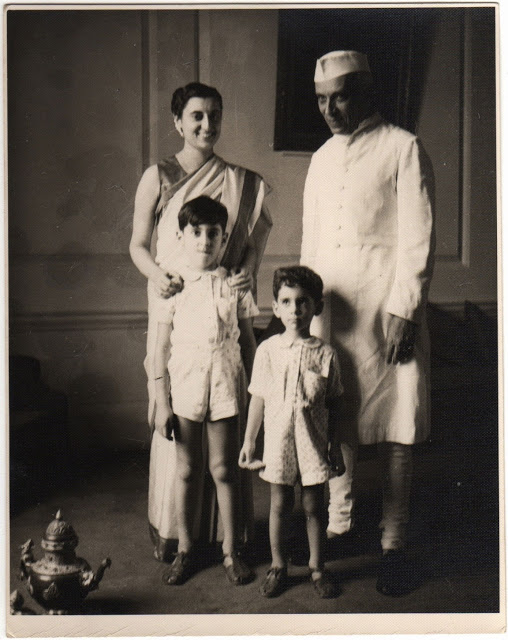

Three generations of Indian leaders are in this picture, taken in 1959: Nehru, his daughter Indira Gandhi, and grandsons Rajiv and Sanjay.

From Old Indian Photos.

Shastri was in turn succeeded by Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi.(6) The main event of her first decade in office was the 1971 war with Pakistan over Bangladesh (see the next section). Agricultural reform, the so-called "Green Revolution," increased food production to the point that India could feed its huge population, for the first time since independence. In 1974 India surprised the world by becoming the sixth nation to explode a nuclear device. Despite that success and the resulting gain of prestige, India waited until the 1990s to build a nuclear arsenal. In 1975 India launched its first satellite, onboard a Soviet rocket.

In 1975 a judge in Allahabad, Ms. Gandhi's hometown, declared her 1971 re-election victory invalid because civil servants had illegally worked on her campaign. In response she declared a state of national emergency, arrested most of her critics, and muzzled the press. Then she implemented strong measures to boost the ailing economy and launched a mass sterilization campaign to lower the birthrate. Yet Gandhi did not have the instincts of a true dictator, nor did she realize her reforms had made her unpopular. In 1977 she called for new elections, the voters kicked both Gandhi out of office, and the country installed its first government without the Congress Party.

The victorious opposition, the Janata People's Party (JPP) had no plans beyond winning the election. Jaya Prakash Narayan, the party's founder, is now credited with saving Indian democracy, but the new prime minister, Morarji Desai, proved unable to run the country any better than Gandhi did. Inflation and unrest came back with a vengeance, and the Janata-led coalition government broke up two years later. That made it possible for Gandhi to stage a spectacular comeback in the 1980 elections, winning a bigger majority than Janata had last time.

In April 1984 an Indian army unit captured the Siachen Glacier, on the northern border of Kashmir. This area had previously been unoccupied and undemarcated; with an elevation reaching up to 21,000 feet, it has been called the "world's highest battlefield" and the "third pole" (from all the surrounding ice). Previously the Pakistanis assumed the glacier was on their side of the Indo-Pakistani border, but when they decided to move some troops there, India got wind of it and acted first. Since 1984 there have been several skirmishes, as Pakistan tried without success to expel the Indians; over the years more than two thousand soldiers and civilians have died at Siachen, usually from frostbite or avalanches rather than from enemy bullets. Currently a cease-fire has been in effect since 2003.

For Indira Gandhi, the previously apolitical Sikhs were a bigger problem than Pakistan. In the early 1980s this group began demanding the creation of an independent Sikh state named Khalistan. Ms. Gandhi responded by giving the police emergency powers in the Punjab. The headquarters and training center for the Sikh militants was their religion's holiest shrine, the Golden Temple of Amritsar. In June 1984 Indian troops launched "Operation Blue Star" and occupied the temple; more than 1,000 Sikhs were killed in the resulting battle, including the Sikh leader, Jarnall Singh Bhindranwale, and the Indians removed a stockpile of ammunition from the temple. Sikhs everywhere saw this episode as sacrilege. Four months later two Sikh bodyguards assassinated Ms. Gandhi.(7)

Rajiv Gandhi, a former airline pilot and Indira's eldest son, became the next prime minister.(8) In two key ways he broke with his mother's policy. Whereas Indira's sympathies were pro-USSR, Rajiv improved relations with the United States, and he encouraged development in the fields of science and technology; that launched today's Indian software and information technology industries. However, the benefits of those reforms would not be fully realized until the end of the twentieth century. In fact, while he was in charge, technology got a black eye because of the 1984 Bhopal disaster; gas leaks from the Union Carbide pesticide plant at Bhopal killed or maimed thousands living in the neighborhood. For Rajiv himself, his reputation as a clean politician was tarnished when it was discovered that senior government officials took bribes from a Swedish guns producer, in return for defense contracts. In the 1989 elections, the Congress Party won a plurality of the vote, but lost its majority, so Rajiv's term in office ended.

The next two prime ministers after Rajiv Gandhi had so many problems, ranging from the economy to the Hindu-Sikh violence, that neither of them lasted for more than a year. In August 1990, the government announced a plan to reserve 49.5% of all government jobs for members of the two lowest castes, the Shudras and untouchables. This attempt at affirmative action backfired when more than 100 upper-caste students protested the plan by burning themselves to death in public. Rajiv Gandhi saw this as his chance to make a comeback and campaigned for re-election in 1991. It looked like he was going to win, but in a small town near Madras, he was killed by a female refugee from Sri Lanka (a member of that island's Tamil separatist movement), who steered a bomb-laden bicycle toward Gandhi and blew both of them up in the act. Gandhi's Italian-born widow, Sonia, refused to run in his place, and that ended the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty.

Is This the Indian Century?

The Congress Party chose Gandhi's foreign minister, P. V. Narasimha Rao, as its next candidate; after what happened to the two Gandhis, he probably accepted with some trepidation. At first Rao was not expected to be anything but a transitional leader, because he had little popular support and was already seventy years old. He had the willpower, though, to make the tough decisions necessary to get India out of the grinding poverty that had marked its history since independence. By this time the socialist program that they had followed since independence was a failure. To give just one example, in 1948 India's per capita income had been equal to that of South Korea, but because the South Koreans had embraced capitalism wholeheartedly, Seoul's per capita income was sixteen times higher in 1991 ($5,600 vs. $350). Furthermore, there was a "brain drain" of the country's elite, as Indian doctors, engineers, scientists, etc., emigrated to English-speaking countries abroad, seeking a better life for their families. And the country's foreign debt had reached $70 billion, one of the world's highest.

With the help of a very capable finance minister, Manmohan Singh, Rao launched a wave of sweeping reforms to give India a free economy and bring the debt under control. Inequities in the tax structure, and barriers to foreign trade/investment, were removed; the rupee was made fully convertible. Major efforts were also undertaken to improve the infrastructure and social services. State subsidies were phased out and the economy was cautiously opened up to foreign investment; multinational corporations were attracted to India's enormous pool of educated professionals, many of whom spoke English and were willing to work for relatively low wages. At first it looked like India was going to default on payment of its foreign debt, but that was saved when the International Monetary Fund gave credits worth $4 billion in 1991, and other banks contributed twice that amount.

In Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, Hindus battled Moslems and the police over a sixteenth-century mosque that the Mogul emperor Babur had built on the birthplace of the Hindu hero Rama. In December 1992 Hindu fundamentalists succeeded in breaking through police barriers, tore down the mosque, and began to build a Hindu temple on the same site. This action led to more Hindu-Moslem clashes across the subcontinent, which killed nearly 3,000 people during the next six weeks.

Social unrest (which included the bombing of city buses in New Delhi) and corruption scandals combined to overshadow the rapidly improving economy, and kept the Congress Party from winning the next election, in 1996. The pro-Hindu Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the most seats in the Lok Sabha (lower house of Parliament), but it did not have a majority either. Consequently there were three prime ministers during the next two years, and only the last one ruled with a majority coalition, because the Congress Party agreed to support him. Still, thanks to Hindu nationalism, momentum was with the BJP, not Congress or any other secular parties. The BJP won the elections of 1998 and 1999, with one of its more moderate members, Atal Behari Vajpayee, as prime minister.

Those elections were held against a backdrop of more trouble with Pakistan. In 1998 India conducted its second nuclear test, and Pakistan, which had been developing its nuclear capability in secret, began conducting nuclear tests just two weeks later. To defuse this threat, Prime Minister Vajpayee made a bus trip to Pakistan in 1999 and met with Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. They signed a peace declaration and started a regular bus service between Delhi and Lahore, but this promising peace process was nipped just three months later when India discovered Pakistani soldiers and local terrorists had infiltrated the Indian-controlled part of Kashmir, capturing the Kargil heights. In the brief Kargil War (May-July 1999), India regained that district, winning another round of high-altitude fighting. Afterwards tensions remained high, due to a standoff between massed forces in 2001-2002.(9)

India finished the twentieth century by becoming the second nation in history, after China, to have a population of 1 billion (May 2000). Following the September 11 attacks in the United States, India became an enthusiastic supporter of the US-led War on Terror. This may have been a factor in the 2002 Gujarat violence; when 59 Hindus returning from a pilgrimage to Ayodhya were burned to death in a train fire, near Godhra in Gujarat, the local government accused Moslems of starting the blaze, causing riots that led at least 2000 people dead and 12,000 homeless. However, a subsequent government investigation ruled that the fire was more likely an accident.

With the 2004 election, the Congress Party made a surprising comeback, led by Sonia Gandhi. The BJP loudly protested against the idea of a foreigner becoming prime minister, until Gandhi stepped aside. Instead Manmohan Singh, the former finance minister, took charge, and formed a coalition with several secular parties, called the United Progressive Alliance. His policy was to continue to loosen controls on the economy, though because the United Progressive Alliance included Socialists and Communists, he had to go much slower than he would have liked. The left-wing parties pulled out of the Alliance in 2008, because they refused to support a nuclear cooperation agreement that Mr. Singh signed with US President George W. Bush, but the rest of the Alliance survived a vote of confidence. Mr. Singh is still prime minister at the time of this writing.

Manmohan Singh.

Mr. Singh's first year coincided with a terrible tsunami that struck all the nations around the Indian Ocean. Along India's east coast, 18,000 were killed and 650,000 were left homeless. Despite the magnitude of this catastrophe, India was able to play a key role in the relief efforts for two countries harder hit, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. The following year (2005) saw more natural disasters: the Mumbai floods (more than 1,000 dead), and a Kashmir earthquake (79,000 killed).

Man-made disasters proved to be a bigger challenge. There were terrorist bombings of trains in 2006 and 2007 that killed 200 and 68 people respectively; the Indian goverment blamed Pakistan, and Pakistan denied any involvement. The deadliest were the Mumbai attacks (November 2008), a wave of shootings and bombings in that city which left 164 dead and 308 wounded. The only terrorist captured alive after that wave revealed the attackers came from Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Pakistan-based group committed to "liberating" Indian Kashmir. Finally, while the standard of living has improved dramatically in recent years, there are still enough poor people in the eastern and southern parts of the country to support an insurgency from the Naxalites, a communist guerrilla movement of the Maoist persuasion.

India's rising fortunes have encouraged it to seek a greater role in today's world; e.g., in 2004 India began campaigning for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. The booming economy is growing at a rate of 7% a year, due not only to the new high-tech industry, but also from the outsourcing of foreign jobs to the Indian labor market.(10) Both the growing economy and growing population promise that India will be one of the most important nations of the twenty-first century, if not an outright superpower. Currently India's main rival is China, but because of China's harsh one-child-per-family policy, China's prospects peaked, along with its population, in 2024; now India is pulling ahead, with 1.45 billion people. Both China and India face a demographic threat from the threat of sex-selection abortions, because both countries have cultures that value boy babies more than girl babies, but because the Indian government does not put pressure on mothers to terminate their pregnancies, the problem is not as serious with India as it is with China. Finally, it looks like the mass famines of India's past are over, and unlike many countries around it, India can be thankful for a democratic government that has stood the test of time.

Pakistan: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

While India has had its challenges since independence, Pakistan has had an even rougher time getting started as a nation. There were eight million refugees to absorb, and the 1947 partition left India with most of the industry, cities, and skilled workers; in addition, the death of Jinnah left Pakistan in the hands of far less capable leadership than India had at the time. Because of this, India developed a successful democracy, while Pakistan has been under military rule for more than half of its existence. Being British-educated, Jinnah and the Moslem League were determined to run Pakistan as a parliamentary state, but in the decade after Jimmah, Pakistan was so unstable that six prime ministers held his office. Because Pakistan was conceived because of Islam, Islamic fundamentalists have tried to give Pakistan a government that strictly follows the Koran. The need to balance the wishes of fundamentalists and modernists, Urdu-speaking West Pakistan and Bengali-speaking East Pakistan, has caused the constitution to be rewritten more than once. And every time a dispute with India arose, Pakistan tried to resolve it by starting a fight it could not win. Altogether it is remarkable that Pakistan survived its first fifty years.(11)

Pakistan, 1947 to 1971. Karachi was the capital until 1960, when construction on Islamabad was finished.

In 1958 the seemingly insurmountable political and economic problems got so bad that the president proclaimed martial law. The commander of the armed forces, General Ayub Khan, ruled the country absolutely for eleven years after that. His regime made some notable achievements in land and political reforms, and government assistance to East Pakistan tripled, but this did not eliminate the economic gulf between East and West Pakistan; the West still held most of the political and economic power.

After the 1965 war with India, Ayub Khan was accused of "losing" Kashmir, and his popularity took a nosedive. Ayub tried to mend his fences, but his opponents were never satisfied, so he resigned in 1969. Another general, Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan, became the next president.

With hindsight, one can see that the idea of Pakistan as Jinnah saw it was politically unworkable. The parts of the subcontinent with Moslem majorities were East Bengal, the entire Indus valley, the "Northwest Frontier" by Afghanistan, the Punjab and Kashmir. There were too many Sikhs in the Punjab to consider giving all of it to Pakistan, for a start. Then there was the already mentioned trouble with Kashmir. Worst of all was the fact that East Bengal was separated from the other Moslem areas by more than 1,000 miles. The people of East Pakistan were shorter, darker, and poorer than their western countrymen. Their theologies were different, too; observers compared the "monsoon Islam" of the East with the "desert Islam" of the West. In fact, East and West Pakistan had nothing in common except Islam--they did not even speak the same language!

Tensions reached a critical mass in the fall of 1970, when a devastating cyclone (Indian Ocean hurricane) slammed into the Ganges delta, killing more than half a million East Pakistanis and leaving an even greater number homeless. Not long after that came general elections: these were Pakistan's first elections, and probably the fairest in the country's history. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a powerful advocate of more autonomy for East Pakistan, campaigned so successfully that the party he founded, the Awami League, won every seat representing the East. Because 56 percent of Pakistan's population was in the East, this gave the Awami League a clear majority in the National Assembly. A former foreign minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, emerged as the most popular leader in West Pakistan.

Yahya refused to have anything to do with these results. Suspecting Mujibur Rahman ("Mujib") of trying to make East Pakistan secede, Yahya postponed indefinitely the convening of the National Assembly. Mujib responded with a civil disobedience campaign that turned into a full-blown independence movement by March 1971. Yahya banned the Awami League, arrested Mujib, and sent the army into East Pakistan. The army made short work of its poorly armed opponents, killing one million Bengalis over the next nine months. Another ten million Bengali refugees fled across the border into India, bringing stories of atrocities with them. The economic, social and health burden created by the refugees was more than India could bear. On December 3, 1971, India declared war on West Pakistan, and marched the Indian Army into East Pakistan; thirteen days later the outmanned and outgunned West Pakistanis surrendered. Yahya ended martial law and resigned, Bhutto took his place, and East Pakistan became an independent nation called Bangladesh ("Bengal Nation").

Under Bhutto's leadership a diminished Pakistan began to rearrange its national life. Putting socialist ideas into practice, he nationalized the basic industries, insurance companies, domestically owned banks and schools and colleges. He removed the armed forces from the process of decision making, but tried to placate them by increasing the defense budget. In 1973 the National Assembly adopted the country's fifth constitution. However, the military did not appreciate its diminished role, and conservatives saw Bhutto's reforms as a threat to Islam. In response, Bhutto became more heavy-handed and authoritarian in the way he dealt with the opposition.

Nine parties united to oppose Bhutto in the 1977 general elections. When Bhutto's party, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), won a major victory, carrying three of the four provinces, he was accused of rigging the vote. Six weeks of demonstrations followed, which ended when Muhammad Zia-ul Haq, the army chief of staff, staged a coup and started a second period of martial law. Bhutto was imprisoned, accused of murdering a political opponent, and hanged in 1979. Instead of preparing for a return to civilian rule, Zia declared himself president, becoming Pakistan's third military ruler.

Whereas Ayub Khan held on to power because he believed only he could run the country right, and Yahya spent much of his time chasing women and drinking, Zia was a puritan who started turning Pakistan into a true Islamic society. It was a disaster. The laws of the Koran became the laws of the land, and special courts were set up to interpret strictly Islamic issues. Banking without interest appeared, and Zia introduced the public floggings of thieves and two-month prison sentences for people seen drinking, eating or smoking during Ramadan. Adultery, defamation, and the consumption of alcohol also became serious crimes. In the name of strengthening both Islam and his rule, Zia grew the intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), into one of the most powerful institutions in the country. The Bhutto family's main rival was Mohammed Sharif, an industrialist and probably the richest man in Pakistan, so as a counterweight to the Bhuttos, Zia gave the Sharifs their company back, which Bhutto had nationalized, and promoted Mohammed's youngest son, Nawaz Sharif, to a position in his administration.

The Soviet invasion of neighboring Afghanistan in December 1979 put Pakistan on the frontline of the Cold War. About 3.8 million Afghan refugees came into Pakistan, and Afghan rebels used Pakistan as their base of operations. In 1980 the Afghan crisis moved US President Jimmy Carter to offer $400 million in aid to Pakistan, but Zia dismissed the offer as "peanuts." However, the United States could not oppose the Russians in Afghanistan without a friendly nation in the region, and after Ronald Reagan succeeded Carter, he offered Zia a better deal. For the next eight years, the United States and Saudi Arabia gave billions in military aid, so Pakistan could manage an anti-Soviet guerrilla force, the Mujahideen.(12) Zia also secretly began a nuclear weapons development program, something the United States had opposed when Bhutto said he wanted to do it.

Despite the Afghan war, the United States wanted to see Pakistan move back toward democracy, so Zia lifted martial law in 1985, though he remained in office as president. In August 1988 he died under mysterious circumstances when his plane exploded in midair. Zia's main opponent, Benazir Bhutto (the daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto), returned from exile, and three months later, she was elected prime minister, becoming the first female head of state in the history of any Moslem country.

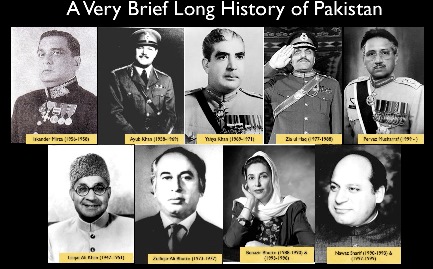

Sixty years of Pakistani leaders, in one picture. Click on the thumbnail to open it full-size in a new tab. Source: A Very Brief Long History of Pakistan I.

The West saw Benazir Bhutto's election as evidence that democracy had been restored. There was much hope that she would succeed, but her first administration lasted only 20 months. Like her father, she could not compromise with her opponents, and she spent much of her time taking on every adversary (both real and potential); it must be admitted, though, that there were many opponents, since both the military and conservatives viewed her weak government with suspicion. Almost no legislation was passed as a result. There were also charges of corruption involving family members, especially her husband. On the foreign scene, the discovery of Pakistan's nuclear weapons project prompted the United States to impose economic sanctions. The last straw was rioting between ethnic groups in Bhutto's native Sind province, which the local government was unable to stop. In August 1990 the normally ceremonial president, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, used Article 58 of the constitution to dismiss Bhutto from office. Nawaz Sharif was elected prime minister in her place, his government did no better, in April 1993 the military dissolved on more charges of corruption. October elections gave a plurality of votes to Ms. Bhutto's Pakistan People's Party, allowing her a second chance as prime minister.

Violence between rival political, religious, and ethnic groups erupted frequently within Sind Province, particularly in Karachi. More than 650 people were killed in 1994 as a result of the violence. In 1996 Bhutto's government was dismissed by President Farooq Leghari amid new allegations of corruption. The following elections brought Nawaz Sharif to power again, in a clear victory for his party, the Pakistan Muslim League. One of Sharif's first actions as prime minister was to lead the National Assembly in passing a constitutional amendment stripping the president of the power to dismiss Parliament (this was one issue where the Bhutto and Sharif families were in agreement!).

During the 1990s, relations between India and Pakistan remained tense, mainly because of the dispute over Kashmir. Diplomatic talks broke down in January 1994, both nations closed consulate offices in each other's country, and Benazir Bhutto resumed Pakistan's nuclear weapons development program. In May 1998 India responded by conducting five nuclear tests; Pakistan matched this with five nuclear tests of its own, becoming the first Moslem country with the bomb.(13) Because India and Pakistan do not have safeguards over their nuclear programs to match those of the West, the prospects for a nuclear war look more likely (and more frightening), than they did when the main arms race was between the United States and the Soviet Union.

While the nuclear tests were criticized by the outside world, they made Nawaz Sharif very popular at home. However, that goodwill was spent when he lost the Kargil War (see above) in 1999. To forestall opposition to his government, Sharif tried to replace the Army Chief of Staff, General Pervez Musharraf, with a general loyal to his family. Musharraf was visiting Sri Lanka at the time, but the army sided with him, so he turned the tables and deposed Sharif in a bloodless coup. Because Sharif had tried to keep Musharraf's returning plane from landing in Pakistan, he was accused, along with his brother and five other officials, of hijacking, kidnapping and attempted murder. Sharif was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, but in 2000 he was pardoned and exiled to Saudi Arabia instead, on the understanding that he would stay out of politics for the next 21 years. As for Musharraf, the Supreme Court approved the October 1999 coup, arguing that the welfare of the nation was the ultimate law of the land. Though it wasn't called martial law this time, Musharraf was granted permission to lead a military administration for the next three years, after which he would have to allow new elections. The Pakistani public went along with all this, figuring another spell of military rule would bring a badly needed economic upswing.

Pakistan in the War on Terror

Osama bin Laden, his terrorist attacks on the United States (especially 9/11), and the US-declared War on Terror put Pakistan in a tricky position. Musharraf devoted a good deal of his time to undoing Muhammad Zia-ul Haq's legacy, so he was inclined to cooperate with the Americans. On the other hand, many, perhaps most, of the Pakistani people favored the terrorists, and Pakistan was one of the three nations that recognized the Taliban as the government of Afghanistan. An alliance with the Americans would destroy the very organizations that Pakistan helped create. However, Pakistan could not put up a serious challenge to the US and India if both of them went against the terrorists, so Musharraf allowed the US-led coalition to use Pakistan as a base when they toppled the Taliban regime in late 2001. Osama bin Laden disappeared at the end of the year, but Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of the 9/11 hijackings, was arrested in Pakistan in March 2002, and handed over to the Americans. Afterwards, relations between Islamabad and the new democratic government established in Kabul were strained, to say the least, and when the Taliban managed to regroup and reorganize, many Pakistanis supported it again. And through it all, Musharraf felt he had to leave his country's 10,000+ controversial Islamic schools (madrassas) alone, out of fear that interfering with them would provoke violent riots.

When the promised elections took place in 2002, Pervez Musharraf won a five-year term as president; opponents and human rights groups called it a rigged referendum. They may have been right; four months later Musharraf introduced twenty-nine constitutional amendments that strengthened his position, making him a Pakistani president with real power. Because he used military force to take over and keep control, he did not seem to realize how inconsistent it was to claim that he was the only person who could restore democracy and economic stability. On a positive note, he was a religious moderate, which gave him good marks abroad, and he allowed the press to criticize him, which gave him good marks at home.

Political matters came to a head in 2007, as Musharraf's term in the presidency drew to a close. He tried to fire the Chief Justice, Iftakar Mohammed Chaudhry, charging him with abuse of power and nepotism, but it backfired when supporters of Chaudhry launched mass protests. Chaudhry had agreed to hear cases of people disappearing who had been detained by intelligence agencies, and constitutional challenges involving Musharraf acting as president and head of the armed forces at the same time, so many felt his dismaissal was politically motivated. In Karachi the protests became violent, as 39 were killed in clashes between pro-Chaudhry and pro-Musharraf rallies. Thus, the Supreme Court ruled that President Musharraf acted illegally when he suspended Chaudhry, and reinstated him. This was soon followed by the siege and storming of Islamabad's Red Mosque, which had become a hotbed for Islamic extremists; more than 80 were killed there.

On top of all that, Musharraf found his re-election would be contested. In August the Supreme Court ruled that Nawaz Sharif could return from exile. Musharraf generously announced that he would allow Benazir Bhutto, who had been also been in exile since 1999, to return, though both she and Sharif still had outstanding corruption charges against them. and they would certainly rebuild their political fortunes once they were back in Pakistan. In October Musharraf was re-elected anyway; the opposition had boycotted the vote, so only representatives from Musharraf's party participated in the election. Twelve days later Bhutto returned, and survived a near-miss from a suicide bomber who blew up in her convoy, killing 135 people. Musharraf declared a state of emergency, suspended the constitution, and fired the whole Supreme Court, including Chief Justice Chaudhry; the last move conveniently headed off an attempt by the Court to contest the election. Then when parliament's five-year-term ended, Musharraf swore in a caretaker government. Under pressure from protesters and the United States, he did promise parliamentary elections in January 2008, and on November 28, one day before his second term began, he stepped down as military commander-in-chief, meaning he would be only a civilian president.

In preparation for the parliamentary elections, Sharif returned from exile, while Musharraf ended emergency rule and restored the constitution in December. However, on December 27, 2007, Bhutto was assassinated in a second suicide attack, that involved both a bomb and shooting, and also killed 23 others. In the wake of the assassination, there was widespread rioting, and two arrested Islamic militants admitted giving a suicide vest and a pistol to the killer. Musharraf postponed the election until February 18, but it did not do him any good; his party, the Pakistan Muslim League-Q, lost its control over Parliament. The Pakistan People's Party, now led by Bhutto's husband, Asif Ali Zardari, came in first place by winning 80 seats; Sharif's party, the Pakistan Muslim League-N, got 66 seats, while the Pakistan Muslim League-Q held onto just 40. Overall this was seen as liberals and conservatives getting together to express their dislike of Musharraf's policies. Sure enough, the Pakistan People's Party and the Pakistan Muslim League-N formed a coalition government, and picked Yousaf Raza Gilani, a former speaker of Parliament in the 1990s, as prime minister.

However, the parties in the coalition could not cooperate after that. In May they argued over how to go about reinstating the Supreme Court justices Musharraf had removed. Then in August they announced plans to impeach Musharraf on charges of violating the constitution, and Musharraf beat them to it, by resigning first. Only one week later, Sharif pulled his party from the coalition, stating he could not work with Zardari anymore. This allowed Zardari to run for president unopposed, and get elected; Bhutto's supporters now controlled the whole government.

Meanwhile on the war front, mopping-up operations in Afghanistan failed to finish off the Taliban, so instead of the war winding down, it heated up for the US and the Pakistani government. The "Talibanization" of remote tribal areas, especially the border district of Waziristan, meant that the terrorists were becoming more powerful in those areas than the authorities. In September 2008 the United States admitted to its first ground attack in Pakistan, sending US Special Operations troops to raid a border village that was home to Al Qaeda members. The terrorists retaliated by exploding a truck bomb outside the Marriott Hotel in Islamabad, killing more than 50 and wounding hundreds. Ominously, the bomb was a few hundred yards from the prime minister's residence, and it went off while the president, prime minister and other senior government members were dining inside.

Zardari came under pressure from outgoing US President Bush and his successor, Barack Obama, to do something about the terrorists, so 2009 saw him launch offensives in the Swat Valley and Waziristan. While these moves were successful, attacks against individuals were more effective. A CIA drone strike in August 2009 killed the Taliban leader in Pakistan, Baitullah Mehsud; he is believed to been behind Benazir Bhutto's assassination, the attack on the Marriott Hotel in Islamabad, and dozens of suicide bombings. His successor, Hakimullah Mehsud, was killed by another CIA drone strike in November 2013. Also helpful were the capture of the Taliban's deputy leader, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, and two regional governors, Mullah Abdul Salam and Mullah Mir Mohammed (all in early 2010). On the other hand, when the website WikiLeaks released released 92,000 classified U.S. military documents in July 2010, they revealed that the ISI, Pakistan's intelligence agency, has been playing a double game, supporting the terrorists in Afghanistan while cooperating with the Americans at the same time.

In May 2011, US Navy SEALs tracked down and killed Osama bin Laden at a three-story compound in the city of Abbottabad. The news that bin Laden had spent most of the previous nine years hiding in Pakistan was considerably embarrassing to the Pakistani government, which had previously denied allegations that bin Laden was in the country. Abbottabad is not far from Islamabad, and has a military base and a military academy; it's a safe bet that bin Laden couldn't have hidden there, in a better than average home, without the support of the ISI, and maybe elements of the Pakistani armed forces as well.

Facing challenges from courts and a hostile military as well as the Taliban, Zardari resorted to a superstitious solution. In 2010 the president's spokesman revealed that he sacrificed a black goat quite often, to get the protection of God against black magic. A politician may still get away with such rituals in certain parts of Africa, but it's not the behavior people expect from the leader of a country with nuclear weapons. You can probably say the goat sacrifices worked, because nothing bad happened to Zardari; however, they couldn't keep his popularity from plummeting after word of this got out, to the point that he decided not to run for re-election in 2013.

Prime Minister Gilani was pressured to step down in June 2012, after he refused to pursue corruption charges against President Zardari; Parliament replaced him by electing Raja Pervez Ashraf, a former cabinet minister. However, the most newsworthy event of the year involved a fourteen-year-old girl. Malala Yousafzai had made a name for herself as an activist, campaigning for the right of all girls to have an education. This is precisely what the Taliban doesn't want, so in October Taliban gunmen shot Yousafzai in the head and neck. Critically injured, she was flown to a hospital in England, where doctors worked heroically to repair the damage, allowing her to make a complete recovery in 2013.

2013 was a milestone year, inasmuch as it marked the first time a civilian government completed a five-year term, making it to the next election without getting interrupted by a coup. Although the Pakistan People's Party remained popular, the political pendulum swung far enough to the right for Nawaz Sharif to put together a coalition of small parties and make himself prime minister, his third time in that position. Pervez Musharraf came back from self-imposed exile to run as well, though he did not get very far. Another member of Sharif's party, Mamnoon Hussain, was elected as the next president.

At this date, Pakistan's future is uncertain. It has been in the news more than most Third-World nations because of its location at the junction of Central Asia, South Asia and the Middle East. Because it is weak compared to India, it has lasted this long through the support of China and the United States. Politically, Pakistan seems to be getting its act together when it comes to running a democracy. However, a large segment of the population favors an Islamic fundamentalist state, and Islam has yet to prove that Shari'a law and democracy can go together. Moreover, the Pakistani government needs a certain amount of Islamic militancy to motivate fighters in Kashmir, keeping alive the chance to gain more of that disputed land. Finally, the United States is losing interest in Afghanistan, after more than a decade of active involvement. If the Americans pull out of Afghanistan completely, without leaving any troops or bases, there is the double threat of the Americans cutting off financial aid to Pakistan, and a revitalized Taliban seizing power in Kabul, which at the very minimum would become a destabilizing influence, among the Pashtun tribes of Pakistan's Northwest Frontier. Trying to be Moslem, democratic, and maintain a strong military at the same time has proven to be a very difficult balancing act, and how Pakistan fares in the future will depend on how long and how well it can keep that act up.

Bangladesh: The Difficult Years Since Independence

Bangladesh is a fairly new state, even by Third World standards. Before the twentieth century it was just the eastern part of a larger Indian state, Bengal, and in the twentieth century it struggled for independence twice, first from Great Britain and then from West Pakistan. Since then Bangladesh has been an "international basket case," as US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger once put it. Because most of the country is a flat, densely populated river delta (the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers all come together here), floods and famine are common, and the region is a magnet for tropical cyclones like the 1970 storm we already mentioned.(14) There has also been the burden of refugees. 270,000 Burmese Moslems, known as Rohingyas, have fled from the militant Buddhist government in neighboring Myanmar, and there are nearly a million other Moslems who do not speak Bengali, collectively called Biharis. Many Biharis came from West Pakistan between 1947 and 1971, and they opposed independence during the 1971 war, so after the war they were stripped of their citizenship and confined to refugee camps. Since then Pakistan has allowed just a few "Stranded Pakistanis" to return to the West, while the Bangladesh High Court has only given citizenship and voting rights to those Biharis who were too young to have participated in the war, or were born after 1971.

Most of the world's nations quickly granted Bangladesh diplomatic recognition; it joined the British Commonwealth of Nations in 1972 and the United Nations in 1974. Much foreign aid came in as well, to get the war-torn and storm-ravaged country back on its feet, but the government could not do anything about the problems of famine and high inflation. By 1975 conditions were so bad that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman proclaimed a state of emergency and assumed dictatorial powers, only to be assassinated in a coup seven months later. But because Mujib had been the founder of the country, the population refused to accept the killers in place of him. Two more coups occurred, and in the following year the army chief of staff, General Ziaur Rahman ("Zia" for short) first became the martial law administrator, then the president.

Order started to return, encouraging Zia to begin dismantling martial law and hold a presidential election, which he won with 76 percent of the vote (1978). Then he formed the country's second important political party, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), and held parliamentary elections in 1979. Unfortunately, these promising signs of a return to civilian rule were abruptly halted when Zia was assassinated in 1981 by a dissident military faction. Ten months later, Zia's successor was replaced in a bloodless coup led by another general, Hossein Mohammed Ershad.

Ershad did better than his predecessors, ruling for eight years (1982-90). At first he suspended the constitution and proclaimed martial law for the usual reasons--bad government and a bad economy. Ershad went on to assume the presidency in 1983. Still, he wanted to give his regime some legitimacy, so he allowed elections in 1986, resigning from the military beforehand so he would not be seen as having an advantage over his rivals. The parliamentary election gave Ershad's party, the Jatiya (National) Party, a slight majority of the 300 available seats, but for the presidential race, the two main opposition parties, the Awami league and the BNP, refused to put forth candidates, protesting that the election would be unfair while martial law was still in effect. Therefore, Ershad carried 84 percent of the vote; others, however, disputed the result and said that voter turnout was far less than the 50% claimed by the government. One month later, Ershad kept his promise to lift martial law.

Less than a year after the elections, the opposition parties began to protest again, because they felt the government was filling too many of its positions with active-duty members of the military. Ershad responded by declaring another state of emergency, dissolving Parliament and scheduling new elections for March 1988. Again, the major opposition parties refused to participate, so the Jatiya Party won big. The political situation was calm for the rest of 1988 and 1989, but then in 1990 opposition to Ershad grew with general strikes, campus protests, public rallies, and overall lawlessness. Ershad was ousted in December 1990 by another bloodless coup, and was subsequently tried, convicted, and imprisoned on charges of corruption and illegal weapons possession. Democracy returned with the holding of new elections in February 1991.

Since 1991, the Bangladesh political scene has been dominated by two women. Begum Khaleda Zia, the widow of Ziaur Rahman, has led the BNP, while Sheikh Hasina Wazed, the daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, has led the Awami League. Most of the time they have alternated as prime ministers; Khaleda Zia held that job from 1991 to 1994, and 2001 to 2006; Sheikh Hasina was in office from 1996 to 2001, and 2009 to present. Under them, politics has followed a predictable cycle:

1. Either the BNP or the Awami League wins.

2. The losing party refuses to recognize the results, and charges the winner with corruption/rigging the results. Strikes follow, and for at least part of the term the losing party refuses to attend sessions of Parliament.

3. Enough people believe the accusations to elect the losing party next time, so in each election, the party out of power wins by a landslide, and the two parties switch places before beginning a new cycle.

Twice (1994-96 and 2006-08), the protests have gotten out of hand, prompting a caretaker government to declare a state of emergency and postpone the elections, until tempers cooled. On August 17, 2005, the protests were interrupted by something worse--200 bomb blasts were inflicted on government buildings across the country. An extremist Islamist group named Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), which wanted to replace the secular legal system with Shari'a law, claimed responsibility for the blasts. They failed to gain support, though, because Islamic fundamentalism has never taken root in Bangladesh, the way it did in Pakistan, and a government crackdown arrested hundreds of senior and mid-level JMB leaders. Another Islamist party, Jamaat e-Islami, has been outlawed because of war crimes committed during the 1971 war for independence; several of its members were tried and convicted in 2013.

In March 2013, President Zillur Rahman had a lung infection so serious that he was flown to a hospital in Singapore, where he died ten days later. This made him the third president of Bangladesh to die in office (coincidentally, all were named Rahman). January 2014 saw the Awami League win national elections, making Sheikh Hasina the first prime minister to be re-elected. Still, we will have to wait a few years to know for sure if the political cycle mentioned above has been broken. For Khaleda Zia and the BNP, my response is, "We will miss you. Until you come back."

Recently Bangladesh has been in the headlines for the worst industrial disasters since the Bhopal gas leaks in India. The country is a major manufacturer of clothing for foreign retailers like J.C. Penney, Cato Fashions and Benetton, and in November 2012 a fire in a garment factory killed 112 employees. Five months later (April 24, 2013), another garment factory building collapsed, killing at least 1,100. While rescue teams were looking for survivors in the wreckage of the second building, another fire broke out, making even the rescue effort hazardous. The building was known to be in poor condition before the collapse, drawing international attention to the lack of safety, limited worker rights, and low pay in Bangladesh's clothing industry. Fortunately the economy has been improving overall, showing a growth rate of 5%-6% a year. Unlike the governments in neighboring countries, the government of Bangladesh has never tried to meddle with wage and price controls, or other forms of "social engineering," so while this is still one of the world's poorest and least developed nations, these days it can usually feed its large population. With the way current trends are going, the future of Bangladesh is brighter now than it has been since it became independent, so it looks like the term "basket case" won't apply to it in the twenty-first century.

Nepal: An Ex-Kingdom In the Clouds

Nepal and Bhutan have a few things in common. Both nations are kingdoms based in the Himalayas, with China/Tibet on the northern border(15), and India facing them from the other three directions. For most of history, both were isolated countries, with few outsiders bothering them. Since the mid-twentieth century, both have been gradually modernizing themselves, and since the twenty-first century began, both have been involved in political experiments.

From 1846 to 1951, all of Nepal's prime ministers came from one family, the Ranas. In 1951 King Tribhuna Bir Bikram Shah ended this system of hereditary rule, which had kept the kings virtual prisoners of the Rana family, and established a cabinet system of government.

Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah became king in 1955. His reign saw more reforms, this time of a non-political nature, to open up the mountain kingdom to the outside world. Roads and regular air service linked Nepal to India and Pakistan, and they built a road over the Himalayas to Tibet. Polygamy, child marriage, and the Hindu caste system were officially abolished in 1963. Political parties were banned, however, in 1960, allowing the king to rule as an autocratic monarch with the consent of a partyless Parliament. In 1972 Mahendra died of a heart attack, and his twenty-six-year-old son, Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, took over.

The first election held in 22 years, on May 2, 1980, approved the existing system of government, but the decade that followed saw a pro-democracy movement take root. By 1990 the movement had grown strong enough that the king was persuaded to lift the ban on political parties and appoint an opposition leader as prime minister until they could hold elections the following year. When the elections took place the campaign was a battle of party icons; since only 26% of Nepal's people can read, they made posters and flags with no words on them, only the party's symbol. For example, a tree represented the Nepali Congress Party, while their rivals, the United Nepal Communist Party, used both the hammer & sickle and a red sun; other parties cluttered the field with pictures of drums, plows, ladders, books and elephants. Most voters simply turned their ballots in with a mark by their favorite party's symbol; many didn't even know the names of the parties or candidates. Out of 205 contested seats, the Nepali Congress won 110, while the communists made a strong second-place showing with 69 seats.

Nearly four years of corrupt and incompetent rule by the Nepali Congress Party angered the masses. In November 1994 they voted again, this time turning the system upside down: the communists won by a landslide. Few of the peasant voters knew they were the allies of the industrial proletariat in the class struggle against bourgeois capitalism, but they cheered for the winners in their victory celebration all the same.

Despite these results, Nepal was an unlikely place for communism, because it was an officially Hindu kingdom. Tradition and tribe, not wealth, produced Nepal's social divisions. What's more, communists are supposed to be atheists. Karl Marx once said that "religion is the opiate of the masses," and the Nepalis were hard-core addicts of that drug. The only reason communism got anywhere was because its followers thought faith and politics were fully compatible; Marxist leaders went so far as to declare that "the principles of Lord Buddha are thoroughly communist."

When the Communist Party's founder, Man Mohan Adhikary, was sworn in as prime minister, he made no move to abolish opposition parties, the monarchy or religion, the way the Chinese did in neighboring Tibet. In fact, the Communists suffered from the same failings as their Congress Party rivals. In 1996 the Parliament dissolved the Communist government, and Adhikary resigned under allegations of corruption. The king swore in members of the Nepali Congress Party and the National Democratic Party as the next two prime ministers, but under them stability did not return. Meanwhile the Communists turned to violence, launching a Maoist guerrilla-style rebellion now called the Nepalese Civil War; it lasted ten years (1996-2006) and claimed more than 12,000 lives.

The civil war wasn't as shocking as the Nepalese royal massacre that happened in the middle of it. On June 1, 2001, Crown Prince Dipendra had too much to drink at a party, and misbehaved so badly that his father, King Birendra, told him to leave. The drunken son was taken to his room, but one hour later he returned to the party with four guns, and proceeded to kill the king, Queen Aishwarya, and seven other relatives before turning a gun on himself. Technically Dipendra was king now, but his gunshot wounds left him in a coma and he died three days later. No one ever found out if Dipendra was motivated to shoot by anything besides drunkeness, or if he acted alone without accomplices. The throne now passed to Birendra's brother, Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev (2001-2008).

As the twenty-first century began, the civil war reached a stalemate, with the military controlling the cities, the Maoists controlling the countryside, and neither able to dislodge the other. Sensing popular support for the monarchy fading, King Gyanendra dismissed the entire government in February 2005, declared a state of emergency, and tried to lead the effort to crush the rebellion all by himself. It didn't work, but in September the rebels agreed to a ceasefire so both sides could negotiate. That led to a "comprehensive peace accord" ending the war, which was signed on November 21, 2006.

King Gyanendra realized that the people were coming to see absolute monarchy as the problem, not the solution, so he agreed to give up his power. The local elections scheduled for February 2006 were called "a backward step for democracy," because the major parties refused to participate and some of the candidates were forced to run for office by the army. The following strikes and street protests in Katmandu persuaded the king to reinstate the dissolved House of Representatives, and that body subsequently voted to make the king a figurehead monarch and declare Nepal a purely secular state. A seven-party coalition took over the government, established a unicameral legislature, and passed an interim constitution. On December 24, 2007, the coalition amended the constitution to say that the leader of the country was not the king but a simple "head of state," thereby abolishing the monarchy and declaring Nepal a republic. New elections were held in April 2008, which the Communist Party won. The ex-king left the Narayanhiti Royal Palace on June 11, 2008, whereupon it was turned into a museum.

Years after doing away with the monarchy, Nepal is still in a state of transition. The government has not written a permanent constitution, to determine the exact makeup of the future republic. This is mainly because of a lack of unity; after getting elected, the Communists soon split along ideological lines, into Maoist and Marxist-Leninist parties. The political scene since 2008 has been one of tensions, power-sharing battles, and governments routinely getting toppled. The most recent Constituent Assembly was elected in November 2013, and it elected Sushil Koirala, a member of the Nepali Congress Party, as prime minister in February 2014. Time will tell if they can last longer and do better than their predecessors.

Bhutan: A Real-Life Shangri-La?

If there is a country in the real world resembling Shangri-La, the fictional mountain paradise, it's the highland kingdom of Bhutan. Bhutan ranks low on world statistics such as life expectancy, literacy, and wealth, but because of the teachings of Buddhism, the people here are some of the happiest anywhere. Indeed, the fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck (1972-2006), talked about raising the country's "Gross National Happiness," and Bhutanese consider that intangible statistic more important than the Gross Domestic Product. Before 1960 Bhutan had no national currency, no telephones, no airport, no schools, no hospitals, and no postal service.(16) Though the country isn't as hard to get into as Tibet, it had very few visitors (none of them tourists), and most of the world didn't even notice it.

Most of Bhutan's early written records were lost when Punakha, the ancient capital, burned down in 1827, so few details on Bhutan's history are available before that date. The land may have been inhabited as early as 2000 B.C. Songtsen Gampo (627-649 A.D.), the earliest Tibetan king we know anything about, converted to Buddhism and in his zeal to spread the new faith, he had two Buddhist temples built in Bhutan. Other holy men came after that, making sure the locals would be devout Buddhists.

There was no unified state here, just a collection of quarrelsome fiefdoms, until the sixteenth century. In 1616 Ngawang Namgyal (1594-1651?), a Tibetan monk, took refuge in Bhutan because he had a dispute with the Dalai Lama's Buddhist sect. He proved to be a talented political and military leader as well as a spiritual leader; by promoting a code of law and building several combination fortress-monasteries called dzongs(17), he brought Bhutan's most important families under one government, with himself as the Shabdrung, or senior lama. Tibet launched three invasions in an effort to stop Ngawang Namgyal before he became too popular, but all were defeated. In 1627 two Jesuits, the first European visitors to Bhutan, came calling at the Shabdrung's court; he was delighted to have them as guests, was reluctant to let them leave, and offered to supply them with the funds and manpower needed to build churches if they wanted to make converts in his country, but when they were done they moved on to Tibet, in search of any Nestorian Christians that might remain in Asia's interior.

Ngawang Namgyal got tired of ruling in 1651, and retreated into a dzong for a prolonged spell of meditation. He never came out again, and probably died soon after entering, but to prevent chaos and a power struggle, provincial officials continued to issue orders in his name, and acted like he was still alive until 1705. There have been thirteen successive Shabdrungs since then, all believed to be reincarnations of the first one. However, they did not exercize as much power as a state council, headed by an elected regent called the Druk Desi. Eventually feuding between different regions led to civil war in the nineteenth century. The main rivalry involved two factions led by ponlops, or provincial governors, the pro-British ponlop of Tongsa and the pro-Tibetan ponlop of Paro. That was the situation when the British arrived in the neighborhood.

Great Britain was not very interested in Bhutan, but it was interested in Tibet, out of concern that the Russians would get involved in Tibet first (see the previous chapter). When they decided to send a military expedition to Tibet, in the hopes of at least opening it up to trade, the current ponlop of Tongsa, Ugyen Wangchuck, gave it his full cooperation, and went along to Lhasa as a mediator. This shrewd move prompted the British to knight him, and he instantly became the most powerful person in Bhutan.

At the same time, everyone had come to realize that the current government, with two weak heads of state, one spiritual and one secular, just could not work very well. Ugyen Wangchuck began to centralize power by removing his chief rival, the ponlop of Paro, replacing him with a pro-British relative. In 1903 the Shabdrung died and it took until 1906 to identify his reincarnation; in the meantime Ugyen Wangchuck acted in his place, taking away whatever power remained to that institution. Finally, in 1907 he forced the last Druk Desi to retire, and at a convention of monks, government officials and the heads of major families, Ugyen Wangchuck was elected as the first Druk Gyalpo, or Dragon King. Since 1907, Bhutan has been a conventional hereditary monarchy, run by the Wangchuck dynasty.

Britain and Bhutan signed the Treaty of Punakha in 1910; Britain doubled the annual subsidy it was already paying to 100,000 rupees, in return for the right to guide Bhutan's foreign policy. That made Bhutan a British protectorate for the rest of the time the British were in India. Indian independence came during the reign of Bhutan's second king, Jigme Wangchuck (1926-52), and initially India replaced Britain as the protecting power, until a new treaty in 1949 guaranteed Bhutan's independence. India also took over paying the subsidy that Britain paid every year, raising it to 500,000 rupees.

The third king, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck (1952-72), wholeheartedly began a modernization program. He was encouraged to do this in part by his European-educated wife, a cousin of the chogyal of Sikkim (see footnote #3). Another powerful incentive was the Communist Chinese conquest of Tibet at the beginning of the 1950s, leading to fears that the Chinese would push on into Bhutan. His twenty-year reign saw the creation of legislative and judicial branches of the government. Other modernizations included land reform, the abolition of slavery and serfdom, the construction of more roads, and buildings like a national museum, national library and stadium. A National Assembly was established in 1953, and in 1968 he gave it the power to remove government ministers and the king himself, if it passed a no-confidence vote by a two-thirds majority. Finally, Bhutan began to pursue a more assertive foreign policy; it joined the United Nations in 1971, for instance.

Jigme Singye Wangchuck was only seventeen years old when his father, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, died in 1972. Still, he assumed his duties as the new king immediately, though his coronation was delayed until 1974. Besides continuing the policy of modernization, he had to deal with guerrilla and refugee problems. In northeast India, more than one faction of separatists wanted Assam to break off as an independent state, and they set up guerrilla bases in the forests of southern Bhutan. The Royal Bhutan Army launched a military campaign that successfully uprooted them in 2003 ("Operation Flush Out"). Meanwhile, there were 4,000 Tibetans refugees in Bhutan, and a large Nepali community (Bhutanese reports said there were 5,000, while refugee reports said over 100,000) that had fled Nepal and Sikkim, especially after the Nepalese Civil War began. The Nepali refugees led to ethnic tensions between Nepalis and Bhutanese, and when this threatened to destabilize the part of Bhutan they were in (mainly the southwest), Bhutan reportedly evicted a large number of them, causing a counter-wave of refugees going back to Nepal and Sikkim. Though Nepal and Bhutan have held negotiations over this issue, they have not reached agreement on who will take in the refugees, so as many as 20,000 have resettled elsewhere, in distant places like Australia and the United States.