| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Africa

Chapter 2: VALLEY OF THE PHARAOHS, PART III

Egypt before 664 B.C.

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Gift of the Nile | |

| The Catfish King | |

| The Archaic or Protodynastic Era | |

| The Pyramid Age | |

| Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt | |

| Egyptian Mathematics and Science | |

| Ancient Nubia | |

| The Late Old Kingdom |

Part II

| The First Intermediate Period | |

| The Middle Kingdom | |

| The Second Intermediate Period | |

| The Rise of the New Kingdom |

Part III

| Thutmose the Trendsetter | |

| The First Feminist | |

| Imperial Egypt | |

| The Amarna Revolution | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part IV

| The Ramessid Age Begins | |

| Ramses the Great, the Ultimate Pharaoh | |

| The Latter Ramessids | |

| The Third Intermediate Period |

Thutmose the Trendsetter

The first three pharaohs named Thutmose were short men with large noses (royal statues are becoming more realistic), and the first one had the same aggressive streak as Ahmose. He would immediately get a chance to fight, too. Egypt's neighbor to the south, Nubia, had appropriate resources for an empire, especially gold, and because it was in the Nile valley, Egypt's rulers saw the Nubian kingdom, Kush, as a challenge to their rightful hegemony. Kamose had annexed Wawat (lower Nubia), and the Nubians had revolted at the beginning of Ahmose's reign. Then when he campaigned in the south, Amenhotep I advanced 90 miles beyond Heh, the most distant Egyptian frontier fort in the past, and built a new one at Shaat. Now the Nubians revolted again, at the beginning of Thutmose's reign; they probably thought this would be a good time for Kush to regain its independence, while Egypt was undergoing a difficult transition between rulers. Thutmose responded by going all the way to the third cataract, stopping barely eighteen miles from Kerma, the Kushite capital. When the battle between Egyptians and Nubians took place, Thutmose did not sit on the sidelines or lead from behind, like today's military commanders; he boldly went forth in the first chariot and personally dispatched the Kushite king with an arrow. He returned to Egypt with a gruesome war trophy -- one relief sculpture commemorating the campaign shows the body of the enemy leader hanging head-down from the bow of Thutmose's boat.

Next, Thutmose I turned his attention to Asia. Because the Hyksos had come from this direction, he saw plenty of potential enemies here, especially Mitanni, a state run by Indo-European charioteers in northern Iraq and Iran. However, previous generations of Egyptians had not visited Asia as much as they had visited other parts of Africa, so this was mostly unknown territory; the purpose of the Asian campaign was exploration more than conquest. We don't know for sure how far he went, but he reported that he defeated his enemies soundly, and "countless were the captives whom the king carried off in his victory." Yet while Thutmose's scribes wrote that "the whole earth is under his two feet," Thutmose did not establish any permanent military bases or colonies, and when the Egyptians went home the local princes stopped paying the tribute they had pledged. One amusing highlight of the expedition is the Egyptian reaction to a river they saw at the point where they decided to turn back. The only river the Egyptians had ever known, the Nile, flows from the south to the north, but this river, either the Jordan or the Euphrates, ran in the opposite direction! Back in Egypt Thutmose's soldiers never got tired of telling about "that inverted water which flows southward when [it ought to be] flowing northward."

For his third expedition, Thutmose went to Nubia again, and this time the Egyptians bypassed Kerma by cutting directly through the eastern desert, thereby capturing the richest gold mines. They returned to the Nile at Kurgus, between the fourth and fifth cataracts. There Thutmose established his authority by leaving this threatening inscription on a boundary stone:

"If any Nubian oversteps the decree which my father Amen has given to me, [his head?] shall be chopped off . . . for me . . . and he shall have no heirs."

The Nubian lands were so important that Egyptian government administered them through a special viceroy, known as the "King's Son of Kush and Overseer of the Southern Lands"; he had as much power as the viziers did in Egypt proper. Under them the Nubians were so thoroughly indoctrinated with Egyptian ideas and customs that in later years, when Egypt had fallen again to foreigners, the Nubians would act more Egyptian than the Egyptians themselves.

When it came to building projects, Thutmose made a complete break with the past. The temples of Thebes were little more than chapels, and that wouldn't do for Amen, who had gone from being the god of one city to the chief god of a mighty empire. Thutmose hired an architect named Ineni to build something more majestic, and Ineni started by building two massive gateways, what we call pylons, in front of the White Chapel from Middle Kingdom days. Then he made the pylons part of a wall around the White Chapel, which added an air of mystery to the temple. The construction was topped off with two obelisks and four tall flagpoles; the amount of stone and imported wood needed for these items suggest that Thutmose spared no expense to get the project done. In this way the White Chapel of Amen was transformed into Karnak, the national temple of Egypt. Many of the pharaohs who came after Thutmose I felt they should work on Karnak, too, so over the next millennium Karnak got many additions, until Thebes was dominated by a truly stupendous temple complex.

Finally, to keep the priests of Amen friendly, the rulers of Thebes appointed a female relative to the job of high priestess, and they called her the "God's Wife of Amen." When Thutmose began his reign, the holder of that title was Ahmose-Nefretari, the wife of the former king Ahmose and the mother of Amenhotep I. Ahmose-Nefretari was the last member of the royal family's old generation, the one that had liberated Egypt from the Hyksos, and her death in the middle of Thutmose's reign must have been seen as the end of an era. To replace her as "God's Wife of Amen," Thutmose chose his eldest daughter, Hatshepsut, though she was probably just a teenager at the time. Remember Hatshepsut's name -- we will be hearing a lot more from her soon!

For his tomb, Thutmose was a trendsetter again; he had a secret cave carved in an isolated valley, behind all the other temples and tombs west of Thebes, and decreed that his mummy and treasures be hidden there. Whereas the pyramids of the past had been built to promote the king and make sure the people remembered him after he was dead, for Thutmose the top priority was security -- the tomb must be concealed to thwart the thieves who had long been a bane to Egyptian cemeteries. Compared with the tombs that would be built here later, the tomb of Thutmose I was small and crudely done; with two passages that curved around wildly, instead of running straight like in other royal tombs; chambers that did not have smooth walls; and decorations only in the burial chamber. In addition, the tomb has suffered some flood damage over the ages, and in two locations the ceiling had collapsed. Obviously the tomb builders were inexperienced, with no veteran workers among them to show how it's done.

The stonecutters, artisans and water carriers who worked on the tomb of Thutmose I lived with their families in Deir el-Medina, a village on the west bank of the Nile. Founded in the reign of Amenhotep I, this village contained 68 houses packed tightly together, with one narrow road running between them and a wall surrounding them all. Presumably the wall was a security precaution, so the workers would not reveal the locations of the royal tombs. The village was later abandoned during a famine in the XX dynasty, and was in very good shape when archaeologists excavated it in the twentieth century. Thus, Deir el-Medina is now considered a time capsule, showing us how middle-class Egyptians lived, though we have to keep in mind that they worked for the government, so they enjoyed a better lifestyle than the typical peasant.

For the rest of the New Kingdom, the pharaohs followed Thutmose I's example, building secret tombs west of Thebes, until they had filled the valley that is now called the Valley of the Kings. As for the funerary chapels that had been built at the base of each pyramid, there wasn't enough room for them in the valley, so mortuary temples were now built between the valley's entrance and the Nile. This may have seemed inconvenient, because it forced the kings' spirits to travel a lot, and the pharaohs made up for this by lavishing upon them nearly as much wealth and labor as they used to spend on the pyramids. Many of these temples, like Deir el-Bahri, the Ramesseum, and Medinet Habu, are now must-see items for today's tourists who journey up the Nile from Cairo.

The First Feminist

More peaceful rulers followed Thutmose I. He had fathered many children, but of the five children who came from his queen, only one--the previously mentioned Hatshepsut--outlived him. Alas, one of the dead children was the crown prince. However, Thutmose had also married Mut-Nofret, a sister of Amenhotep I, after he came to the throne, and Mut-Nofret bore three sons; the oldest of those sons, also named Thutmose, would now become the next king. We saw previously that both the kings and queens of Egypt were expected to have royal ancestry, so incest had become the sport of kings, making for some wildly tangled family trees. In this case, it meant the younger Thutmose would marry Hatshepsut--his half-sister. Thutmose II was barely twenty years old, physically and mentally weak, and largely dominated by his strong-willed wife.

As king, Thutmose II was a great under-achiever. We know of two military campaigns from his reign, one into Nubia and one into the Sinai, but it does not look like he went with either, instead letting a general lead each one. When it came to building, we know he built a gateway for the temple at Karnak, but if he built anything besides that and his tomb, his name was erased from it. Thutmose and Hatshepsut may have been married for as long as twenty years, but because he wasn't healthy, we don't think he ruled for long. The Egyptologists who examined the mummy of Thutmose II have called him the ugliest of the Thutmoses, so one of them, Bob Brier, remarked that for Hatshepsut, it must have been a long twenty years. Their marriage may not have been a happy one, because after Thutmose II checked out, Hatshepsut left several inscriptions, but while some of them mentioned her father, Thutmose I, she never mentioned her husband again.

Here is how Will Cuppy and William Steig viewed the relationship between Hatshepsut & Thutmose II. From The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody, New York, Barnes & Noble Books, 1950, pg. 20.

With the death of Thutmose II, the succession problem came up again, for he had his sons by harem girls. A six-year-old was crowned King Thutmose III, and married to Hatshepsut's daughter, Neferure. To manage affairs of state until the young king grew up, Hatshepsut became regent; this made her Thutmose's stepmother, aunt and mother-in-law, all rolled into one.

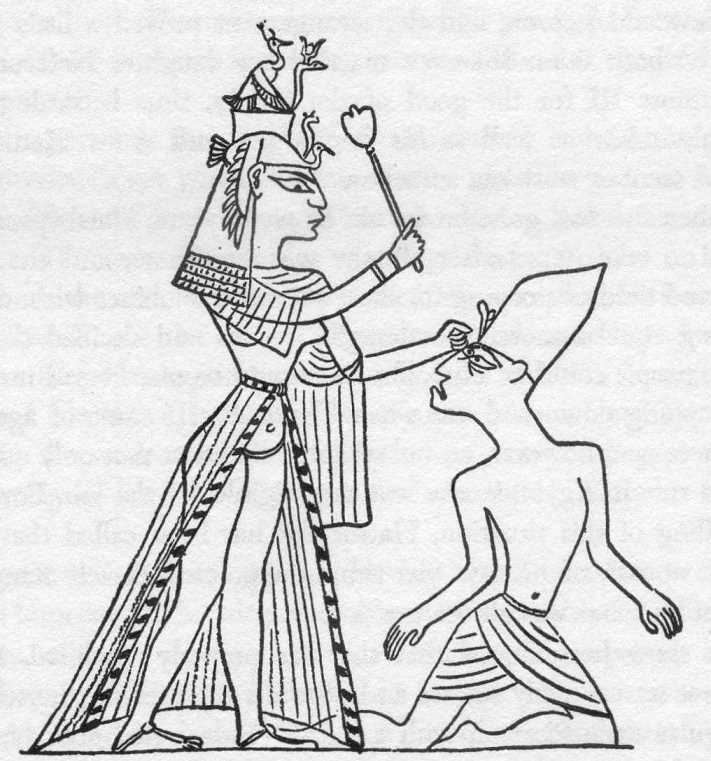

Queen Hatshepsut was uncommonly ambitious for a woman in ancient times, so much so that I call her "history's first feminist." After serving as regent for a few years she abruptly declared herself "king." Her claims were dubious; technically a woman could not rule on her own, and the few who did in the past, like Merneith and Sebek-Neferu, were either temporary regents, or short-lived substitutes who got the job when the dynasty ran out of men. A propaganda campaign was needed to make Hatshepsut's rule legitimate. First she told the story that her father Thutmose I had really wanted her to rule, but was forced by tradition to bequeath the throne to Thutmose II instead. Then she changed how she looked in the art. Early in her reign the artists made statues and paintings of her that showed a normal queen, but as time went on her image became androgynous, less woman-like. Eventually the artists portrayed her as a "king," with a flat chest, a man's kilt instead of a dress, and a man's beard. By this time she had also changed her origin story. No longer simply claiming to be the rightful heir of Thutmose I, she now ordered the making of relief sculptures which showed the god Amen-Ra approaching her mother in the guise of Thutmose I at the time of Hatshepsut's conception, meaning that she was really of divine birth. And since she was now calling herself a king, her previous title, "God's Wife of Amen," became inconvenient, so she gave the job of high priestess to her daughter Neferure. Finally, she took for herself all of the customary royal titles except "Mighty Bull," which clearly was not appropriate for a woman who described herself as "exceedingly good to look upon, . . . a beautiful maiden, fresh, serene of nature, . . . altogether divine." The Egyptians did not have a word for a female ruler at this time (the word we translate as "queen" is the word for "god's wife"), so Hatshepsut's reign mangled the language and caused much confusion among the scribes, who had to call their master "king" whether they liked it or not (see also footnote #5).

Hatshepsut came from a family of warrior monarchs, so she was probably expected to launch some military campaigns against Egypt's enemies. It looks like she sent four expeditions into Nubia and Asia, and she personally led the first Nubian campaign, at least. But she never seemed overly interested in the war-leader part of her job, and her reign is now usually remembered as twenty-two years of peace. It certainly helped that foreign rulers gave Egypt no trouble while Hatshepsut was in charge; for some reason they did not want to mess with her!

Most of the time Hashepsut's activities were administrative, repairing temples and tombs ruined during the Second Intermediate Period, building new temples, and pursuing commercial ventures. The latter became the high point of her reign, when she sent five cargo ships to trade with the fabulous land of Punt. Pictures from this voyage were carved on the walls of her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, which she built next to the temple Mentuhotep II had built, at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom. The Punt expedition thus went down as the greatest shopping trip of all time, and we regard Hatshepsut's temple as the most elegant in Egypt.

Hatshepsut never remarried after she became "king," but she had a close affair with an architect named Senmut, which seems to have begun while Thutmose II was alive. Likewise, Senmut remained a bachelor all his life, very unusual in a society where everyone is expected to marry, even priests. Of course Senmut had a hand in Hatshepsut's construction projects, especially Deir el-Bahri. She needed Senmut's talents so much that he rose from a lower-class family to become the richest man in Egypt during a twenty-year career of active public service; eventually he held no less than 80 official titles. His wealth and his association with the queen showed in his preparation for eternity; not only did he build a fine tomb for his parents, but he built two for himself, the latter one right in the Deir el-Bahri complex. Later on, however, his images were erased from the temple and his sarcophagus was smashed; unfortunately, we don't know if this meant Senmut fell out of the queen's favor, or if an enemy got revenge on him after his death.

And what about Thutmose III, the boy who was supposed to be the real king? Hatshepsut sent him off to become a priest; this was always a good job to have in Egypt, and it kept him away from the royal court. Then she looked for a way to make Neferure "king," instead of Thutmose. However, Neferure may have died first, because we have no inscriptions mentioning her after the eleventh year of Hatshepsut's reign.

By this time, Thutmose III was nearly grown up. Although only 5' 3" in height, he was clearly a stronger man than his unlucky father, and his favorite activity was military training, for the day when he would lead armies to war. "He used to shoot at a copper target," wrote one admiring scribe. "It was an ingot of beaten copper, three fingers thick, with his arrow stuck in it, having passed through and protruding on the other side by three handbreadths . . . I speak accurately of what he did . . . After all, it was in the presence of his entire army." When he was old enough, he went on one of Hashepsut's military campaigns into Asia, which gave him some valuable experience.

In the sixteenth year of her reign, Hatshepsut made another bold move by holding the Heb-Sed, or jubilee festival, to prove to everyone she was still fit to rule. When this ritual was established in the I dynasty, it was supposed to take place after the king had been on the throne for thirty years. It looks like Hatshepsut justified holding it early by adding the years when she shared power with Thutmose II, and maybe even the tail end of Thutmose I's reign, to prove that she had been making important decisions for thirty years, not just sixteen. At any rate, after passing the endurance tests that made up the festival, she looked more like a real "king" in the eyes of those who might challenge her authority.

When Thutmose III was ready to rule by himself, Hatshepsut still did not step down. However, time was running out for any alternatives to Thutmose. Between Hatshepsut's sixteenth and nineteenth year, Senmut disappeared, and finally Hatshepsut herself perished. We have seen how the Egyptians outdid everyone else when it came to elaborate burials, but curiously, Hatshepsut never finished the tomb being built for herself; instead, the tomb of Thutmose I was opened, enlarged, and Hatshepsut was buried in there. We don't know if she did this because she felt the need to declare herself a legitimate ruler one more time, by having herself share a tomb with a male ruler everyone considered legitimate, or if she simply wanted to be reunited with Dad in the afterlife. An examination of Hatshepsut's mummy (identified in 2007) revealed that she lived into her fifties, and had been afflicted with bone cancer and diabetes.

Though he allowed Hatshepsut to have a proper funeral, Thutmose later felt the need to erase any evidence that a woman had ruled before him; he chiseled Hatshepsut's name off the monuments, and ordered her inscriptions erased, her reliefs defaced, and her statues broken and thrown into a quarry.(23) He never explained why he did this, and we used to see the desecration as a sign that Thutmose had a grudge against Hatshepsut; many books have reported that Hatshepsut kept Thutmose suppressed while she was alive, so when he was on his own, an angry Thutmose destroyed the legacy of Hatshepsut. More recently, however, it has been pointed out that Thutmose left the monuments alone until his Aunt Hattie had been dead for twenty years; in other words, it looks like he didn't act until memories of Hatshepsut threatened his legacy. For reasons also unknown to us, some of the destruction of Hatshepsut's legacy was even carried out by the next pharaoh after Thutmose, Amenhotep II. Finally, Thutmose had men go to the Valley of the Kings, and open the tomb of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut. They removed the mummy of Thutmose I and everything that belonged to him, and placed them in a new, better tomb (called KV38 by archaeologists). Because they left Hatshepsut's mummy behind in the original tomb, this action shows that Thutmose III did not want to destroy Hatshepsut; he just wanted everyone to forget the great queen.

Before he did all the things mentioned above, Thutmose III had a larger task to keep him busy--it was time to unleash the army. During the two generations since Thutmose I marched into Asia, the rulers of the Asiatic cities had stopped paying the tribute they promised to Egypt, so on the first day of his reign, Thutmose III proclaimed a general mobilization of the armed forces.

Imperial Egypt

During the thirty-two years of his reign (fifty-four years, if you count the period when he was Hatshepsut's junior partner) Thutmose III led his army on seventeen campaigns as far away as Syria, and according to his accounts, won every one of them.(24) While Hatshepsut reigned, the cities Ahmose and Thutmose I claimed to have conquered cast off their bonds and invited the kingdom of Mitanni to invade Syria. By the time Thutmose III became king, the Levant was united in a coalition of 330 Canaanite princes allied with Mitanni and commanded by the king of Kadesh.

Thutmose viewed the first campaign as his greatest military triumph; in this one he marched up the coast all the way up to Mt. Carmel; the most daring part came when he bravely went through a very narrow but unguarded pass and surprised his enemies at Megiddo, the main fortress of the coalition, though Megiddo itself had to be starved out in a seven-month siege. The Egyptians also plundered the enemy's camp outside the city; the booty brought back included Megiddo's grain (which the locals did not have time to harvest before the Egyptians arrived), 924 chariots, 200 suits of armor, 2,232 horses, 3,929 cattle, 20,500 other animals, and 1,796 male and female servants. Thutmose also returned with 87 children of Asian nobles, who were educated in Egyptian ways so they could return as pro-Egyptian governors when they grew up. As expected, they fondly remembered the time when they "had been taken to Egypt as children to serve the king as their lord and to stand at the door of the king."

The remaining princes of Syria and the Holy Land were quick to switch their allegiance from Mitanni to Egypt; kings from as far away as Assyria dispatched gifts to the conqueror. Thutmose, however, did not consider the task to be finished. Every spring for the next fourteen years he led his legions into Asia. It is beyond the scale of this work to recount these campaigns in detail, except for a couple of high points. First he captured the ports of Phoenicia (Lebanon); this allowed him to transport his troops by water and provided advance bases for his most distant campaign, against Mitanni. For these he had boats loaded on oxcarts and hauled more than 250 miles, so they could be used to navigate the Euphrates. When he conquered Syria the king of Mitanni refused to meet him in battle, withdrawing to the mountains and leaving behind only 636 soldiers for the Egyptians to capture. In response Thutmose crossed the Euphrates and devastated Mitanni's homeland, bragging that he turned it "into red dust on which no foliage will ever grow again." Most of Syria now fell into the Egyptian orbit.

One group of foreigners got special treatment from the Egyptians. The Minoans, inhabitants of the island of Crete, were the greatest sailors before 1000 B.C. To everyone else the sea was an obstacle to overcome, but to the Minoans, it defended their homeland, and provided food and jobs. The Egyptians respected that, because they had also used boats for as long as anyone could remember, but were spoiled by living on a river that was so easy to navigate; Egyptian sailors were definitely out of their element when they went to sea. From the Egyptian point of view, all foreigners except Minoans were simply barbarians.

I am mentioning the Minoans here because one of the most exciting discoveries in recent years was a small palace containing Minoan-style art, found at Avaris in the 1990s. It had been built during the Hyksos era, and remained in use in the early XVIII dynasty. The palace could have served as a Minoan trading post, but several cities in Lower Egypt are closer to the sea, so it is more likely that this was where the Minoan ambassador(s) stayed, while in Egypt. After Thutmose III, Egyptian-Minoan contacts abruptly stop, so we now believe the famous Santorini volcanic eruption, that wasted Crete and the other Aegean islands, happened during Thutmose's reign.

Thutmose and his successors chose to govern their Asian holdings leniently, often leaving native princes in charge and only using Egyptian soldiers to garrison a few key spots. Of course, native uprisings were bound to happen, so the pharaohs tried to talk them out of it. One pharaoh warned a vassal king: "If for any reason you harbor any thought of enmity or hatred in your heart, then you and all your family are condemned to death." On the other hand, they promised considerable rewards for loyalty: "If you show yourself submissive, what is there that the king cannot do for you?"

Though he may have been done with Asia, Thutmose wasn't yet ready to settle down, so in the 47th year of his reign he led an expedition that completed the conquest of Nubia. After taking Kerma, he pushed on past the fourth cataract to Kurgus, where he left an inscription that exactly matched the one of Thutmose I. Then he stopped; the fertile Dongola Reach had given way to the more arid region of Karoy, meaning that the land ahead was too poor to support his army, and communications with Egypt were so stretched that it would have been dangerous to keep on going, so this became the farthest frontier. Still he was able to receive the submission of Irem, a kingdom above the fifth cataract. Later on Thutmose's son, Amenhotep II, would found the town of Napata as a trading center near the fourth cataract, and a temple to Amen at nearby Gebel Barkal; Napata would become the new capital of Kush when it regained its independence.

According to Sir Alan Gardiner, the "Egyptian empire" was not really an empire in the modern sense of the word--one huge nation containing many peoples, all ruled by a single monarch.(25) It was more like the Soviet Bloc of the twentieth century--a "superpower" nation claiming that the smaller countries around it were independent, when they were in truth satellite states under puppet rulers. We often call Thutmose III "the Napoleon of Egypt," and his name appears on every list of great kings, since historians tend to like exciting, warlike kings more than dull, peaceful ones. However, for the whole three thousand years of ancient Egyptian history he is a notable exception; most pharaohs were content to stay at home. The important point to make is that the Egyptians never seemed to have a "Napoleon complex" to conquer the known world; their motives for conquest were to give Egypt buffer states for defensive purposes, and to enrich Egypt by gaining control over the major trade routes of the day. It appears that Thutmose drew the line in Syria not so much for logistics reasons, but because he was getting too old to travel any farther. It would not be until the rise of the Assyrians that we see the spirit of Babel restored, with kings devoting themselves to nothing but the grabbing of as much real estate as possible.

The Egyptians did not try to colonize the lands they conquered, because nothing could persuade them that life anywhere else was as good as it was in Egypt. Even more important, they had a phobia against being caught dead (literally) abroad; if they died in a place where people did not know how to give a proper Egyptian-style funeral, they would lose their chance at the all-important afterlife. The Egyptian garrisons were small for the same reason (e.g., a letter from the king of Jerusalem mentioned fifty Egyptian archers stationed there), and you can bet the soldiers were happiest when their tours of duty were short.

Under Thutmose III the Egyptian army became a fully professional force of 20,000 men, organized into four divisions or brigades which were named after gods (the Brigades of Amen, Ra, Ptah and Sutekh respectively). We hear of staff officers like the "master of the horse," who managed the horses and chariots; the "keeper of the army registers," who was in charge of personnel (i.e., conscription); a "keeper of hostages" to watch over prisoners; and the pharaoh's personal retinue, which included "the king's charioteer," "the king's bow-carrier," "the king's armor-bearer," and even "the king's barber." These staff officers were not paper-pushers who stayed a safe distance from the action, like their counterparts today, but were expected to go with the pharaoh into battle, at the front of the army. They were rewarded well for the risk, though; one barber was allowed to keep the prisoner he captured as a personal slave, while a king's butler received seven head of cattle.

The life of the lowly infantryman was hard, as it has always been, but it was no worse than the backbreaking labor spent by those who worked on the farms of Egypt or on the pharaoh's construction gangs. Moreover, the ordinary soldier probably did not receive regular wages for his service, though he did receive food, clothing, shelter and medical attention. The benefits were a chance to gain the spoils of war, and the chance to rise in rank to eventually become a battalion commander. Thus the scribes were no longer the only ones who could rise from a family of nobodies to become the confidant of kings. Of course most of the good jobs were reserved for friends and relatives of the pharaoh, but whoever proved his ability could expect to receive from a grateful pharaoh gifts like jewel-encrusted weapons, gold necklaces, or grants of tax-free land. In peacetime the generals were given civil assignments like overseeing the temples, priests, or part of the bureaucracy. This combination of military and civilian offices in the hands of the same people made it possible for an ambitious officer to take for himself any position in Egypt's conservative society--eventually that would include even the awesome office of pharaoh.

The next pharaoh, Amenhotep II, was not a great man, but he was a big one. Whereas we noted the Thutmoses had been on the short side, Amenhotep II stood six feet tall, making him a giant by the standards of the day. He boasted constantly of his athletic achievements, and fought a few campaigns in Asia to prove what a super jock he was.(26) A large bow that he claimed no one else could draw was buried with him, in his sarcophagus.

Amenhotep II never bothered to name a successor, so a crisis broke out upon his death, because he left two sons that were eligible for the throne. The elder son, also named Amenhotep, must have looked the most promising; he had gained experience by competently performing the jobs his father had assigned to him, and was favored by most of the royal family. By contrast, Thutmose, the younger, inexperienced son, does not appear to have had much support, except from his mother and the vizier of Upper Egypt. Nevertheless, Thutmose was the one crowned, becoming Thutmose IV, and he gave us an extraordinary story on how he did it.

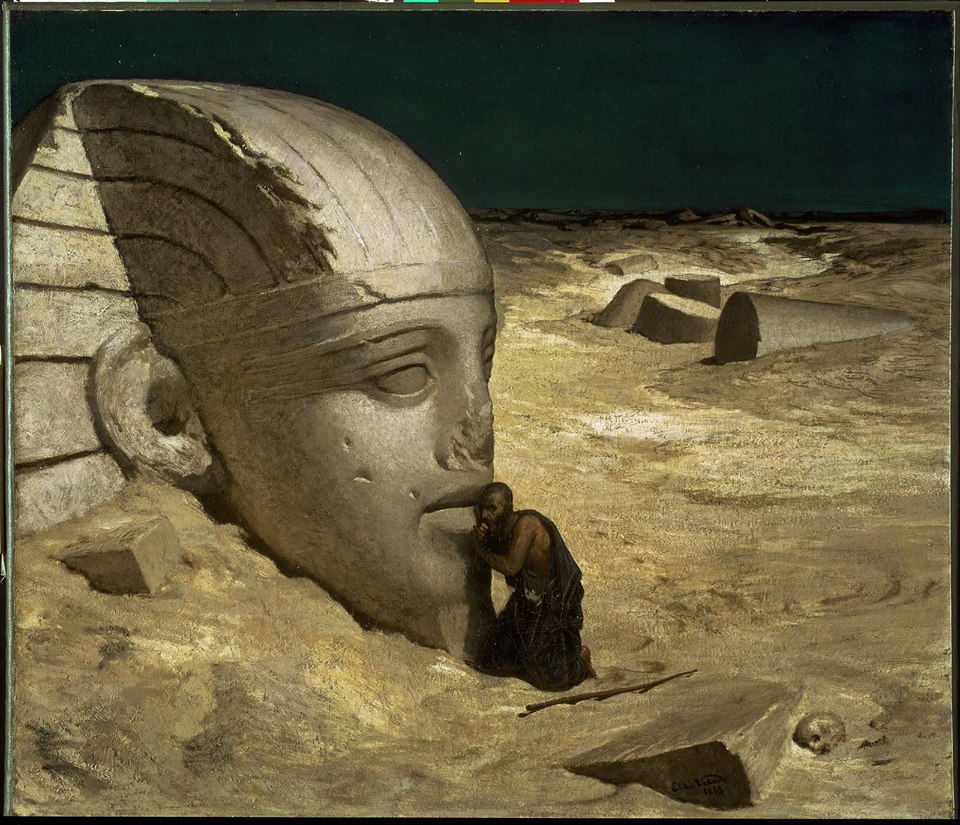

The story is written on a stela (stone tablet) between the front paws of the Great Sphinx at Giza. In Thutmose's day, the Sphinx was already more than a thousand years old, and buried up to its neck in sand. The stela tells us that when Thutmose was a prince, he went hunting in the neighborhood, and took a mid-day nap in the shade of the Sphinx. While sleeping, the Sphinx appeared to him in a dream, and promised him that if he cleared away the sand, the Sphinx would make him king. Thutmose promptly organized a team of workers to do what the Sphinx requested, and sure enough, he became the next pharaoh. Unfortunately, we do not know if the younger Amenhotep and his backers simply stepped aside when they learned about Thutmose's act of kindness to a god, or if a violent revolution followed, in which Thutmose came out the winner. After Thutmose IV took over, he gave his brother the same treatment that Thutmose III had given to Hatshepsut, destroying all records he could find that mentioned the younger Amenhotep; that certainly didn't make the job of historians and archaeologists easier.

Thutmose IV was definitely not as healthy as his predecessors; he ruled for about ten years, compared with at least twenty-six years for Amenhotep. You could call him the "King of One," because his achievements are singular: one military campaign (in Nubia), one hall added to the Karnak temple, one chapel built (also at Karnak), one obelisk raised, and the one story told above. To his credit, the obelisk was 105 feet tall, making it the largest seen in Egypt up to this date.

In foreign affairs, the former rival, Mitanni, became an ally of Egypt, and they teamed up to stop the growth of some dangerous new empires, namely Hatti and Assyria. Relations were so good that a Mitannian princess was given in marriage to Thutmose. Art, dress and styles of speech also came under foreign influence. The cities conquered in the previous century remained loyal to Egypt; they sent tribute, their princes did not dare to challenge Egyptian supremacy, and their children were raised and educated in the pharaoh's court. At home Egypt enjoyed a level of prosperity that had never been attained before and would never be reached again. Gifts arrived from the Hittites, Assyrians and Babylonians; in return, foreigners asked the pharaoh "for gold, for gold is as common as dust in your land." The nation that was once happy to be isolated now found itself dealing with foreigners constantly.

As the glory and serenity of the Old Kingdom can be seen in the pyramids, so the power and wealth of the Egyptian Empire went to build the temples at Thebes. Here stand the great mortuary temples on the west bank of the Nile, and the magnificent temples of Karnak and Luxor on the east bank. The latter form the second largest structure ever built for religious purposes; only the temple city of Angkor Wat in Cambodia is bigger. By itself the Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, built by Ramses II, is larger than the cathedral of Notre Dame; its 134 columns are arranged in sixteen rows, with the roof over the two broader central aisles (the nave) raised to allow the entry of light. This technique of providing a clerestory over a central nave was later used in Roman basilicas and Christian churches.

Officially the capital of Egypt was still at Thebes, which was not only home to the founders of the Middle and New Kingdoms, but also had several important temples. However, the densest population had always been in the north, so most of the bureaucracy had to stay in Memphis. The result was that Thebes served as the religious capital, while Memphis was the administrative capital. Typically the royal family spent time in both cities every year, because the pharaoh was expected to take part in more than one religious festival, in different parts of the country. In the next section we will see what happens when a new capital is built, exactly halfway between Thebes and Memphis, and the pharaoh who moved there liked it so much that he stopped traveling altogether.

The Amarna Revolution

Both Thutmose IV and his successor, Amenhotep III, must have been happy that the empire gave them little trouble. Amenhotep III is sometimes called "Amenhotep the Magnificent," because XVIII-dynasty Egypt peaked during his reign. He had access to more wealth and manpower than any other pharaoh, at least until the age of the Ptolemies (see Chapter 4). When it came to military matters, he only fought in one campaign, to put down a rebellion in Nubia, and the rest of the time he gave himself over to the pursuit of pleasure. He was definitely a person of more refined, softer fiber, than his tough Theban ancestors. For example, an angry elephant nearly killed Thutmose III on a hunting expedition in Syria. When Amenhotep III decided that it was time for him to earn a heroic image, he did it safely; he ordered that wild bulls be penned up in an enclosure. "Then," says the chronicle, "did His Majesty proceed against all these wild bulls. Tally thereof: 170 wild bulls."

Amenhotep was a child when he came to the throne, no more than twelve years old. Fortunately, the court found a scribe talented enough to manage the kingdom for him: Amenhotep, the son of Hapu. A resident of Athribis, a town in Lower Egypt, this Amenhotep had already lived a productive life in his community, and was around fifty years old when he was summoned to the pharaoh's court. This by itself made him a remarkable man; most Egyptians in those days did not live that long, and here he was starting a new career at that age. Besides being a scribe, Amenhotep-Hapu filled the jobs of priest and architect, and the pharaoh would need the latter skill, to build monuments to the glory of the gods and himself. Once he even led an army unit in the Nile delta. The mission of these soldiers was to stop an incursion of nomads from the desert, and to defeat some pirates raiding the Mediterranean coast. The pirates were called the "Peoples of the Sea," a name we will be hearing more during the next two dynasties, so don't forget it. Eventually Amenhotep-Hapu attended the first Heb-Sed of Amenhotep III, so we know he lived to be at least eighty; imagine how that must have amazed his contemporaries!

When it came to mortuary temples, the temple of Amenhotep III was the grandest of all. Unfortunately he made the mistake of having it built on the Nile floodplain, instead of where the western desert began, so every time the Nile flooded, its water reached the structure. As a result, the temple eroded away faster than expected; all that remains of it today are the foundations and the pharaoh's giant statues, the famous "Colossi of Memnon." By contrast, Malqata, the chief palace of Amenhotep III, was also built on the west bank of the Nile, and is the best preserved palace of any pharaoh. It was probably one of the largest palaces in Egypt, because Amenhotep enjoyed a longer than average reign, and it looks like the palace was remodeled at least twice.

As might be expected, the luxury-loving example of the pharaoh encouraged nobles and the middle class to indulge in whatever they could afford. The noble's house was a whitewashed villa with as many as thirty rooms, lit by light coming in through clerestory windows and decorated with paintings of birds and flowers in vivid blue and green and orange, while gold-trimmed columns held up the ceiling. Popular pastimes included lounging by pools and gardens fragrant with flowers, playing a board game called senit, or listening to the harp. Almost certain to be found at home was one of the first domesticated cats, which the Egyptians called by the phonetic name of miu. Those who could afford more than a loincloth or a simple cloth wrap wore new, fancy fashions such as pleated skirts, and adorned themselves with wigs made of human hair and jewelry made of gold and semiprecious stones like turquoise, carnelian, and lapis lazuli.

Egyptian women had a variety of makeup and beauty aids, like mirrors, razors and tweezers, and myrrh or oil of lily to use as perfumes. Aphrodisiacs were available to arouse failing passions, and other magical formulas were alleged to turn rivals into withered crones.(27) A sage urged husbands to give their wives a respected place in the household: "Do not supervise your wife in her house if you know she is doing a good job . . . Do not say to her, 'Where is it? Get it for me!' when she has put it in the proper place." Wives also had the legal rights to own and dispose of property, and to get one third of the couple's possessions in case of divorce.

Amenhotep kept peace at home and abroad the same way King Solomon did, by marrying the sisters and daughters of many important figures. Besides the usual Egyptian girls in his harem, he added two Mitannian princesses, two from Syria, two from Babylon, and one from the kingdom of Arzawa, in what is now western Turkey. Even with those women, he had an insatiable appetite for more. "Send beautiful women," he urged one provincial governor, "but none with shrill voices. Then your king and lord will say to you, 'That is good.'"

Amenhotep, however, considered love more important than politics, because he chose Tiy, a strong-willed woman, to be his queen. Her father, Yuya, was an army officer and a priest of Min, god of fertility.(28) A brother of hers named Anen was a senior priest of Amen and chancellor or goveror of Lower Egypt. We also think a future vizier named Ay was another brother of hers; we'll be hearing from him again later. All this means that Tiy came from an important family, but she was not a blood relative! It was a major scandal in ancient Egypt to give the queen's crown to a commoner, and that may have been a factor in the upbringing of the next king.

Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy.

For Tiy's enjoyment, the king created a beautiful artificial lake, measuring 6,400 by 1,200 feet, next to the Malqata palace. Despite the immensity of the project, the scribes claimed it was completed in only fourteen days. The lake gave boats on the Nile direct access to the palace, and Amenhotep and Tiy also spent many happy hours on that lake, idly drifting around in their royal boat.

Together, Amenhotep and Tiy had six children, but nobody suspected that this happy family was about to give the land a radical upheaval. The eldest son, Thutmose, was sent to Memphis to become a priest of Ptah, the god of that city. Because Memphis was so important, the ancient Egyptian equivalent of New York City, Ptah was a major god in the Egyptian pantheon, too.(29) When the high priest of Ptah died, Thutmose presided over his funeral, though he may have been just a child, and then he was promoted as the new high priest. He also appears to presided over the oldest known burial of an Apis, a sacred bull. In the XVIII dynasty, each Apis was buried in a small tomb, in the desert west of Sakkara; the Serapeum, the famous catacomb at Sakkara for the mummies of sacred bulls, would be built in the next dynasty. Meanwhile, each of Amenhotep's four daughters got appropriate jobs for royal princesses.

However, no position was given to the younger son, Amenhotep IV. This simply could have happened because the younger Amenhotep was not yet old enough to hold an important job. But the statues and paintings that we have of him after he grew up suggest another possibility; he was the "ugly duckling" of the family, and his relatives kept him out of public view to avoid embarrassment.

Fate said otherwise, though, for natural disasters can strike at any time, even when a nation's rulers are good and the economy is healthy. There was one in the third decade of Amenhotep III's reign, a really bad epidemic. We think it was malaria, but some Egyptologists have also suggested bubonic plague. Four members of the royal family died during this time, and it looks like they were victims of the epidemic. Three of them were senior citizens: Queen Mother Mutemwiya, the widow of Thutmose IV and mother of Amenhotep III, and Tiy's parents, Yuya and Tuya (see footnote #28). While these individuals had already done their part to perpetuate the dynasty, the fourth death was a real tragedy for Egypt: Crown Prince Thutmose. At most he was in his early twenties; it is possible he had not reached adulthood. Now Tiy acted; she had enough power to make her other son the heir to the throne, instead of one of the king's sons by a concubine.

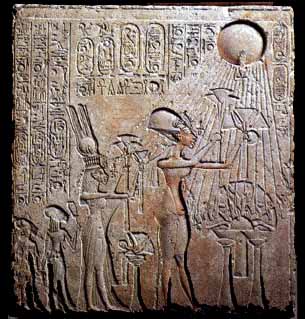

It may have been toothaches that gave Prince Amenhotep the break he needed. In his later years Amenhotep III, now a thoroughly debauched character who experimented with wearing women's clothing, was portrayed by artists in an unusually realistic manner: obese, sagging, and listless. He was tortured by the pain of abscessed teeth, and his doctors could not do anything about it, except sedate him with wine and opium (this drug was available from Mycenaean Greek traders). Thus, he wrote to the king of Mitanni, asking him to send an image of the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar from Nineveh so her famous healing powers could bring some relief. From the thirtieth year of his reign onward, Amenhotep also had himself portrayed in art as an incarnation of the gods Amen, and Ra-Horakhty, a composite god that combined characteristics of Ra and Horus. Amenhotep had Ra-Horakhty portrayed as a falcon-headed man with a sun-disk on top of his head. Sometimes the sun-disk could be shown by itself; in that form it was called the Aten, and it had a hand on the end of each sunbeam to bless worshipers with. Thus, whereas previous pharaohs had claimed to be the son of a god, Amenhotep was calling himself a sun god. It looks like he did this to cover up the fact that he was getting old, and his physical strength was failing. Still, he was in no shape to run the country, so some historians believe that shortly before his death he crowned Amenhotep IV, and allowed him to run everyday affairs as co-regent.

When he first became pharaoh, Amenhotep IV made it look like he was continuing in the footsteps of his father, by raising an obelisk to Ra-Horakhty in the temple of Karnak. He also took a wife, the famous Queen Nefertiti, as one would expect a king to do if he was serious about perpetuating the dynasty. But then in the second year of his reign he made a speech to his courtiers that showed he was going to break tradition. Unfortunately only fragments of the speech have come down to us; it looks like he declared that the gods had abandoned the temples and their worshipers, except for one god -- the Aten. Therefore, he would launch a new project, the construction of a new temple complex in the desert east of Karnak, dedicated solely to the Aten. In an area that may have been half a mile long, he built two temples, one showing images of himself worshiping the Aten, and the other temple showing images of Nefertiti doing the same thing. And unlike the temples of the past, these temples were completely roofless, exposing those inside to the full power of the Aten.

In the third year of his reign Amenhotep broke tradition again, by celebrating the Heb-Sed festival, instead of waiting thirty years to do it. Now Amenhotep III lived long enough to take part in three Heb-Seds, and it is possible that he was too sick for the second or third one, so if Amenhotep IV was crowned before the third festival, he could have taken his father's place. Or Amenhotep IV could have done it because when a pharaoh came out of the festival, he enjoyed considerable power over the priests, and that would help with what came next.

During the ceremonies around the Heb-Sed, the Aten was given equal billing with Amenhotep, as if Egypt now had two kings. You can see this from the royal symbols that were added to the Aten. The name "Aten" began to be written in a cartouche; that had been done with the names of kings and queens since the IV dynasty, and now the god's name got the same treatment. And the sun-disk was now portrayed with a sacred cobra or uraeus, a symbol of kings going all the way back to predynastic Lower Egypt. In addition, Amenhotep began to levy a tax on the temples, which previously had been tax-exempt; the major temples in the country now had to contribute labor and supplies for the construction of the Aten temples at Karnak. In that way the Aten instantly became as rich as the older gods. But even with all this, the new pharaoh was not satisfied. The name Amenhotep means "Amen is content," and it was a painful reminder of what his ancestors believed in, so in the sixth year of his reign he changed his name to Akhenaten, meaning "the spirit of the Aten."

Amenhotep, now Akhenaten, proclaimed that the Aten was the only true god. He closed the temples to Amen and had Amen's name chiseled off the monuments; this also meant defacing the monuments built by Amenhotep III because the name of the king's father contained the name of the hated Amen. Citizens were ordered to follow the pharaoh's example and change their names if they had a name that honored the discredited Amen. Other gods were ignored most of the time, but their images and names could get removed as well, if they were portrayed with Amen. On top of that, Akhenaten overturned the priesthood by declaring that only himself, the "beautiful child of the Disk," could speak directly with the god, which meant that he was the world's only legitimate priest and prophet. Consequently he didn't try very hard to promote Aten-worship, beyond whatever city he was living in at the time.

Speaking of cities, Akhenaten built a brand new capital city, halfway between Memphis and Thebes. The site he picked was a grim desert, with cliffs surrounding it on three sides and the Nile on the fourth. No gods were worshipped there, no people had lived there previously, and only Akhenaten would wish to make a home there. Because of that, the location suited him perfectly. To the east of the city, one can see two mountains, and every morning, the sun appeared to rise in the valley between those mountains. Some Egyptologists have suggested the view convinced Akhenaten to build the city here, because he named it Akhetaten, meaning "the horizon of the Aten." The modern-day village at that spot is Tell el-Amarna, so an alternate name for the late XVIII dynasty is the "Amarna period." Laid out in a grid pattern, rather than with roads winding in every direction, Akhetaten may have been the first city that was planned before it was built. To speed up construction, small stones cut into a shape resembling bricks, called talatat, were used (they had also been used for the Aten temples at Karnak). Akhenaten was so eager to live in his new city that he set up a giant tent for himself and his court, four years before the buildings were ready for use. For the rest of his life, he never left Akhetaten again. Because this tent-dwelling group was led by a nonconformist, you could call it the first hippie commune! At the peak of its short lifespan, the city held between 20,000 and 50,000 people.

Akhenaten's zeal in promoting monotheism is shown in his Hymn to the Sun, which many have compared to Psalm 104 in the Old Testament ("O Lord, how manifold are thy works!"). A few lines show its lyric beauty and its conception of one omnipotent and beneficent Creator:

"Thy dawning is beautiful in the horizon of the sky,

O living Aten, beginning of life!...

How manifold are thy works!

They are hidden before men,

O sole god, beside whom there is no other.

Thou didst create the earth according to thy heart

While thou wast alone."(30)

Akhenaten and his family worshiping the Aten.

Akhenaten's reformation, like many others, was directed primarily against the venal priests of his day, who had grown very powerful over the ages, and turned their places of worship into storehouses of wealth, usually accumulated at the expense of the faithful. Temple treasuries held the nation's surplus grain, priests often sponsored trading expeditions abroad, and the scribal schools were run by them. Because the priesthoods controlled much of the ordinary Egyptian's life, Akhenaten's attack on the gods was devastating. Obsessed with his own god, the pharaoh paid little attention to secular matters and allowed corruption to creep into the bureaucracy. While Akhenaten preached his crusade, officials bribed and stole, public works deteriorated and trade dwindled.

On a positive note, the religious revolution caused a revolution in art. Akhenaten adopted as one of his titles the epithet "living in truth," and commanded that all portraits show how his family really looked, which gave Egyptian art a realism never seen before. Before this time all of the pharaohs were portrayed stiff and formal, looking so much alike that we cannot identify their statues if there is no name on them.(31) But now the king was shown enjoying life with his family, playing with and kissing his children, which would have been unthinkable to earlier artists. The tabby cat of Queen Tiy is shown sleeping under her chair at the dinner table, enjoying more privileges than she normally gave to humans. The treasures found in Tutankhamen's tomb were made during or immediately after Akhenaten's reign, showing us that the art of Egypt was never better than it was during this time.

Akhenaten also gave himself a new look; he had artists depict him with a long head, hatchet-face, thick lips, thin neck, narrow shoulders, potbelly, swollen thighs, and spindly lower legs. This has led to speculation in our own time that he had a glandular disorder, or a hereditary disease like Marfan's Syndrome.(32) However, it now appears he was really creating a new artistic convention. The god he worshipped was sexless, so he wanted to be shown with both male and female features. It has also been suggested that Akhenaten took opium, and both the religious visions and the new art conventions could have come from what he saw while high.

The rosy picture painted by the Amarna artists was only an accurate description of life for the top ten percent of the capital's population. Recently archaeologists examined the cemeteries where the common folk were buried. To start with, there were four cemeteries containg the remains of 13,000 bodies, a disturbingly high number for a city that was only inhabited from the 5th to the 17th year of Akhenaten's reign. These graves were tightly packed and marked with piles of rocks; most of the dead were rolled up in stick mats, because they could not afford coffins or mummification. The researchers declared the skeletons in the graves were the most stressed and disease-ridden skeletons to have been found in Egypt so far. Children showed signs of malnutrition, like scurvy and stunted growth; an astonishing number of adults had arthritis and healed fractures, presumably work-related injuries from carrying all those talatat around. The overall analysis of the skeletons shows an average life expectancy that could have been as low as fifteen years. Because of their harsh living conditions, and because Akhenaten's monotheism was too cold and intellectual to have much appeal for those who yearned for a blessed hereafter, the middle and lower classes did not give up their favorite gods. In various parts of the capital, archaeologists have also found small statues of gods that were popular among the masses, like Bes, the god of luck, and Bastet, the cat goddess; the workers who built Akhetaten brought their gods with them to their new home.

In 1887 Akhenaten's state archives were discovered at Tell el-Amarna. 363 clay tablets were found, written in Akkadian cuneiform, which was apparently the language of diplomacy before 800 B.C. In these letters Amenhotep III is called "Nimmuria," and Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten is addressed as "Naphuria." The letters were written by the kings of the city-states and countries of Asia, most of which had been subjugated by Egypt under the Thutmoses. These letters tell a woeful story: for more than twenty years the Asian vassals asked Amenhotep III and Akhenaten for aid against raiders of the desert and the enemy "king of Hatti." Unlike their predecessors, neither pharaoh led an army into Asia, and little aid was sent (Akhenaten was too preoccupied with his revolution at home, and Amenhotep III apparently was too old and sick to care). This letter from the Jebusite king of Jerusalem is an example:

" All the lands of the king have broken away . . . The Habiru are plundering the lands of the king. If no troops come in this very year, then all the lands of the king are lost."

The Habiru mentioned in this letter sound like "Hebrews," and if one follows a conservative Bible chronology, this would suggest that Akhenaten lived at the same time as Joshua or the first judges. However, most historians feel that "Hebrew" is an incorrect translation: the word Habiru(33) can also mean "cutthroats," meaning any band of ruffians coming into the land.

Beyond the Euphrates River, Egypt had no shortage of enemies. Kings like Burnaburiash of Babylon, and Suppiluliumas of Hatti (the so-called Hittites of eastern Turkey) sent Akhenaten letters that were decidedly unfriendly. When Akhenaten continued to leave Syria unattended, the city-states of that region were forced to switch their allegiance to Hatti. The Egyptian empire thus fell to pieces.

Akhenaten's revolution came undone while the empire did. His health declined and it is possible he even went blind; Herodotus talked about a blind king named Anysis. In the seventeenth year of his reign he "went to the Aten," cause of death unknown.

Akhenaten's eldest son Smenkhkare ruled for about a year, but we are not sure if that brief reign came after Akhenaten, or he was a co-regent, ruling with Akhenaten at the same time. It now looks like upon Akhenaten's death, Queen Nefertiti changed her name to Neferneferuaten, and took the throne for herself, but her reign wasn't much longer than Smenkhkare's -- three years at the most. Neferneferuaten compromised with the priests of the old gods by allowing repairs to the temples of Amen in Thebes, though it appears she stayed in Akhetaten and continued to follow the Aten. When her reign ended, the throne went to Smenkhkare's younger brother, a nine-year-old boy named Tutankhaten. Because of his age, two other men ran the country: an aged vizier named Ay, and Akhenaten's chief general, Horemheb. Under their direction, the young king abandoned Akhetaten, moved the capital of Egypt back to Thebes, changed his name to Tutankhamen, and died before his nineteenth birthday. Worship of the old gods came back into style, and Egypt's monotheistic revolution was over.

The "boy-king" didn't accomplish much, because of his youth and because he was apparently in poor health during his short lifetime. Though we have pictures from his tomb of him riding in a chariot, fighting Syrians and Nubians, it is unlikely he ever went to a battle. Nor is he known for his acts of diplomacy, or political dealings. And when it came to monuments, his activities were limited to some repairs and additions to old temples; he did not start any spectacular projects. The reason why Tutankhamen is famous today, is because of all the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, his was the most intact. The discovery of "King Tut's treasures" by Howard Carter in 1922 has been hailed as one of archaeology's greatest discoveries. We learned little history from the boy-king's golden trove, though; the tomb was too small (only four rooms) to contain many inscriptions, so it served best as a time capsule for the vivid art of his time.(34)

Surrounding the mummy of Tutankhamen were four shrines of gilded wood, a stone sarcophagus, and three man-shaped (anthropoid or mummiform) coffins. They were arranged so that each piece fitted inside the others, like a Russian doll. The innermost coffin, shown here, is made of solid gold.

Tutankhamen's only children, two baby girls, were both stillborn. Since there was no heir, it looks like Horemheb was supposed to succeed him, but he was away from Thebes at the time of Tutankhamen's death, so Ay took charge of the burial. The tomb was small because a larger tomb was intended for him originally, but it was unfinished; he must have died unexpectedly. There are signs that the burial was a rush job, using an empty tomb and whatever grave goods were handy. Still, Ay spared no expense on the funeral; although Tutankhamen was one of Egypt's least important kings, we believe he got the same grave goods and ceremonies that were given to the royal superstars, and maybe even more than them. No doubt the Egyptians gave Tutankhamen credit for bringing back the old religion; what's more, he would have been the first pharaoh in more than sixty years to receive a proper burial (the last was Thutmose IV). By presiding over the funeral and marrying Tutankhamen's widow, Ankhesenamen, Ay established himself as the next pharaoh. Then he appropriated the unfinished tomb meant for Tutankhamen, and completed it for himself. However, he only ruled for four years and like his predecessor, died childless, so General Horemheb took over after him.

Despite his military background, Horemheb was an administrator rather than a conqueror; his main interest was managing Egypt right. He knew the country needed time to recover from the excesses of the previous generation, so his reign was a time of peace. During this recovery, he erased all memory of the Aten and its sponsor, Akhenaten. The heretic pharaoh's desert city and temples were torn down, his statues were demolished and his name was removed as zealously as he had removed Amen's; future Egyptians would call him "that criminal of Akhetaten." In addition, Horemheb swept out the corruption that had crept in since Akhenaten's reign. Many venal officials, especially tax collectors, were punished by cutting their noses off and exiling them to El-Arish, a town in the Sinai peninsula (for a while the Greek name for the place was Rhinocolura, meaning "cut-off noses"). Finally, he rewrote history by erasing Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen and Ay from official records, and added their reigns to his own, making it look like he was Amenhotep III's successor, and that he had ruled for fifty-nine years.

Horemheb tried to secure a place for himself in the royal family by marrying Mutnodjmet, a sister of Nefertiti, but they failed to have any sons. Mutnodjmet's skeletal remains, found in a tomb at Saqqara, give us an idea of what happened; her pelvis showed evidence of trauma from multiple births, perhaps as many as thirteen, and she was buried with the last infant, suggesting that either the baby was stillborn, or she died in childbirth. As a result, Horemheb ended up designating another general, Pi-Ramessu, the son of an army officer named Seti, as his heir. Pi-Ramessu had proven his loyalty and competence by serving as Horemheb's vizier, and even more important, he had a son and a grandson, so putting him on the throne promised stability for three generations. Pi-Ramessu returned the favor by posthumously declaring Horemheb an honorary member of his family. Most history texts simply call Horemheb the last ruler of the XVIII dynasty, but because of this "adoption," you can also call him the first ruler of the XIX dynasty, if you care to. As for Pi-Ramessu, he would go down in history as Ramses I, the founder of an age of glorious revival.

This is the end of Part III. Click here to go to Part IV.

23. Thutmose plastered over Hatshepsut's best obelisk, but here the queen had the last word. The plaster preserved her hieroglyphics for us to read, and later it fell off, so they are clearly visible today. Hatshepsut did allow Thutmose to put his name on her monuments, but underneath her own and in smaller hieroglyphics. After he took charge Thutmose erected his own obelisks; four of them now adorn the cities of Istanbul, Rome, London, and New York, where they are incorrectly called "Cleopatra's Needles."

24. If you want to read more about the Asian campaigns of Thutmose III, check out Chapter 2 of my Middle Eastern history.

25. Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs, New York, Oxford University Press, 1961, pg. 230.

26. On one campaign, Amenhotep II bragged that he beat two hundred ordinary men in a rowing contest, by rowing his boat farther than any of them could. Another time he claimed that he spent a whole night at the only entrance to a camp full of prisoners, guarding it with just a few servants at his side. Still other times were devoted to hunting and archery practice.

27. One such recipe, made of worms boiled in oil, was supposed to make an enemy's hair fall out when applied to the victim's head. To remove body hair, bat's blood was the preferred depilatory. To protect against the worm recipe, or to stop falling hair from any other cause, beauticians recommended regular applications of hippopotamus fat on the head!

No, you're doing it wrong.

28. Because of Tiy's exalted status, her parents, Yuya and his wife Tuya, received a fine tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

Very few non-royal people were buried in the valley. Besides Yuya and Tuya, one of them was a mysterious young black man named Maiherperi (also spelled Maihirpre). His tomb contained a vase bearing the name of Amenhotep II, but the style of the burial is very similar to that of Yuya and Tuya, so archaeologists guess that Maiherperi lived at the same time, in the reign of Amenhotep III. Whoever he was, he received the best burial that money could buy; the tomb contained a personalized copy of the Book of the Dead (see Footnote #13) with his picture in it, and his mummy is so well preserved that in one picture I saw, he didn't even look dead! Maiherperi may have been a Nubian prince who came to Egypt for his higher education, as part of the program introduced by Thutmose III, but died before graduating; at least he appears to have been a favorite in Pharaoh's court.

29. It has been a thousand years since Memphis was the capital of Egypt, but until the founding of Alexandria (see Chapter 4), it would remain the largest city in the country, thanks to its superb location. Over the millennia it held more than one name. The oldest name we know of is Inbu-Hedj, meaning "the White Walls." In the First Intermediate Period it was called Djet-Sut ("Everlasting Places"), which was also the name of the pyramid of Teti; in the Middle Kingdom, it was Ankh-Tawy ("Life of the Two Lands"), a reference to its location where Upper and Lower Egypt meet. By the beginning of the New Kingdom the name had become Men-Nefer ("Enduring and Beautiful"). The Coptic language translated this as Memfi, and from this we get Memphis, which is a Greek name.

During the New Kingdom, the main feature of Memphis was its grand temple to the god Ptah, called the Hwt-K3-Pth or Hut-Ka-Ptah. Late in his reign, Amenhotep III commissioned a major building project in Memphis, which included either a new temple to Ptah or an expansion of the existing one -- we're not sure which, because most of Memphis has not been excavated by archaeologists. He probably did this because his influence needed to be seen in the city, but now he was too old and sick to travel there from Thebes.

Mycenaean Greek merchants who visited Memphis called it by the name of its temple complex, and gradually the Greeks started applying that name to the whole country. In the Greek language, Hut-Ka-Ptah became Aiguptos; later the Romans translated this name to Aegyptus. And that is how Egypt got the name we use today; to ancient visitors it was the land of the great Memphis temple.

30. J. H. Breasted, The Dawn of Conscience, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1939, p. 284.

31. Before Akhenaten the main exceptions to this rule were the squinting pharaohs of the late XII dynasty. The statues of Amenhotep I had a faint smile.

32. The recent identification of Akhenaten's body has ruled out the idea that pictures and statues of him were realistic. In 1907 Theodore Davis, an American Egyptologist, found a badly preserved tomb in the Valley of the Kings, labeled KV55 by Egyptologists. The mummy was in a woman's coffin; the hieroglyphics on the coffin were hacked off, making a solid identification impossible. The coffin had also fallen and broken open--either the pallbearers dropped it, or it was on a table that has since disintegrated. Rain had gotten into the tomb in the past, causing decay to set in; only a few bones from the mummy could be saved. At first the bones were identified as female, possibly those of Queen Tiy, but then a second examination revealed that the bones belonged to a man who lived to be 25 or 26. People started speculating that the bones belonged to Akhenaten, but very few religious leaders start their careers as children, so by the mid-twentieth century, Smenkhkare had replaced Akhenaten as the most likely occupant of the tomb. More recently it turned out that the examiners were wrong twice; a CAT scan of the skull in 2007 gave an estimated age between 37 and 60, so Akhenaten became the leading candidate again. Finally, DNA tests were done on the Amarna-era mummies in 2010, and they identified the man in KV55 as a very close relative of Tutankhamen, either his father or his brother.

That apparently settled the matter--Akhenaten was the man buried in KV55. Obviously the tomb and the burial were not up to the standards you'd expect for a pharaoh, so we believe that he was hastily buried here by friends or relatives inexperienced in tomb preparation, to escape the wrath of those who undid the Amarna revolution after Akhenaten's reign ended. Akhenaten had a tomb built for himself in the desert east of his capital, but it doesn't look like he ever used it.

The only unusual physical feature that showed up in the KV55 mummy was an elongated head. Members of Akhenaten's court had themselves portrayed the same way Akhenaten did, and we know it wasn't because they caught the same disease. Like the squinting faces of the Middle Kingdom, this was pure symbolism, done to show that the subject was on the same team as anyone else who looked like that.

33. 'Apiru in Egyptian.

34. Grave robbers did break into Tutankhamen's tomb, but they only made off with a few small items before they were caught. After that, a bit of luck saved the tomb. Egyptians forgot about the boy-king, and another pharaoh, Ramses VI of the XX dynasty, built a much larger tomb above Tut's; the debris hauled out from that excavation was dumped on top of the site where Tutankhamen was buried, leading future robbers to believe there was nothing else around to steal. Ramses VI was not so lucky; when priests came to his tomb to rescue what the robbers left behind, they found the royal mummy hacked to bits!

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Africa

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|